Academic Innovation Initiatives Update

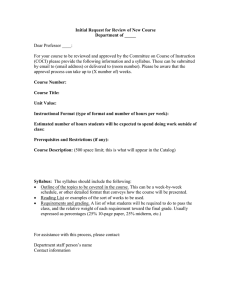

advertisement