Parkinson Society Saskatchewan: Working Together to Meet Member Needs A Research Report

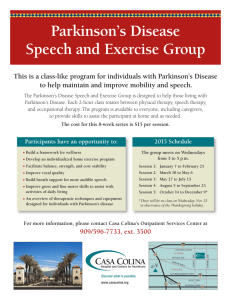

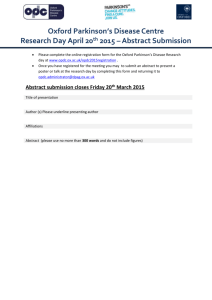

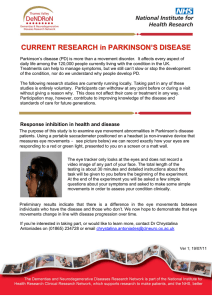

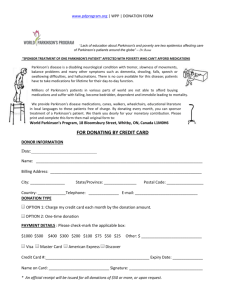

advertisement