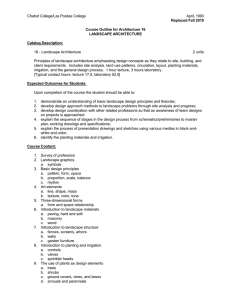

UNIFIED FACILITIES CRITERIA (UFC) LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

advertisement