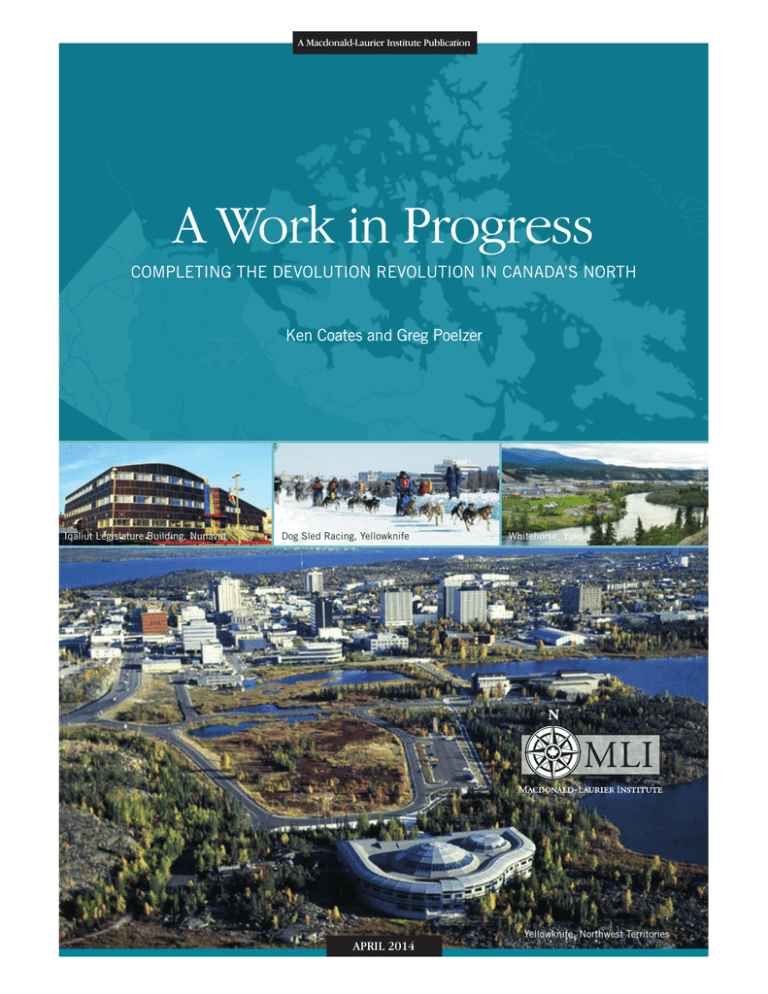

A Work in Progress COMPLETING THE DEVOLUTION REVOLUTION IN CANADA’S NORTH

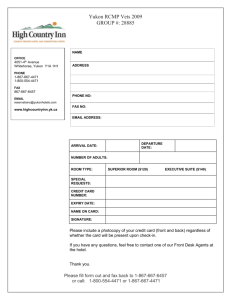

advertisement