Community-University Institute for Social Research TOWARD IMPLEMENTATION OF THE

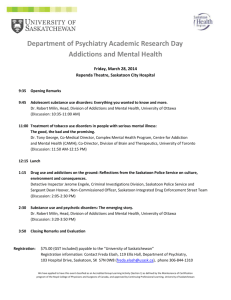

advertisement