Growing Pains Social Enterprise in Saskatoon’s Core Neighbourhoods

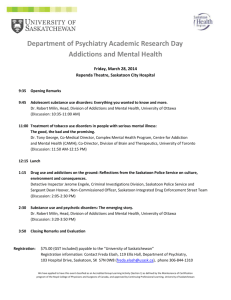

advertisement