Alexander and the Greeks in Egypt More than Trade and Sex

advertisement

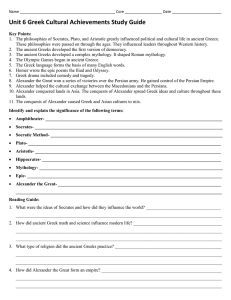

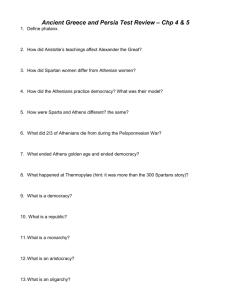

Alexander and the Greeks in Egypt More than Trade and Sex By Debbie Challis 1 Mycenean IIIB1 stirrup vase (UC16631) 2 Fragment of red-figure pottery (UC19358) 9 11 2b Statuette from Naukratis (UC1649) 8 7 3 Scales from Persian body armour (UC74787) 2 6 4 Alexander terracotta head (UC49881) 3 5 Alexander as Heracles, plaster cast of cameo from a ring (UC2458) 1 6 Two-handled drinking cup (UC19372) 7 Ostracon list in demotic (UC71101) 8 Gorgon terracotta medallion (UC48468) 10 9 Cartonnage mask (UC45850) 2b 5 4 12 10 Handle of lamp showing Serapis (UC54426) 11 Terracotta figures (UC35954, UC75914, UC35953). 12 Ptolemaic display case. Introduction [. . .] shouted acclamations in Greek, and Egyptian, and some in Hebrew, charmed by the lovely spectacle— though they knew of course what all this was worth, what empty words they really were, these kingships. C. P. Cavafy, Alexandrian Kings (C.P. Cavafy, Collected Poems. Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard. Edited by George Savidis. Revised Edition. Princeton University Press, 1992) Alexandria in Egypt was created and named by Alexander the Great, King of Macedon and ruler of the Greek world. One of many Alexandrias established by Alexander and scattered across the known world in the fourth century BC, its fame still resonates. The Greek poet and twentieth-century Alexandrian C. P. Cavafy captured the echoes of the past in the city in his poem ‘Alexandrian Kings’. It has become a cliché that history is written by the victors. As with all clichés this is both true and trite; victors try to write the history. It is no accident that Alexander the Great was accompanied on his travels and wars by an, at first, tame historian Kallisthenes, whose work is lost but informed the later historians Polybius and Plutarch. Once Ptolemy I Soter became ruler of Egypt after Alexander's death, he wrote his own history of Alexander and the Macedonian conquests. Ptolemy then commissioned Manetho, a native Egyptian, to write a history of Egypt from the first dynasty to the time of Alexander's conquest in 332 BC. Again this work is lost, but informed the work of the Romano-Jewish historian Josephus who wrote in the 1st Century AD. Alexander could not control the dissemination of his history, but his name and exploits are renowned to this day. On the left; a contemporary statue of Alexander the Great in Alexander Square, Nea Pella. A modern town next to the ancient palace and city of Pella, the capital of the kingdom of Macedon. On the right; part of an image of a hunting scene from a pebble mosaic in a house in Pella, birthplace of Alexander the Great. The image is sometimes identified as Alexander the Great. Page 2 of 12 The wresting of Egypt from Persian control by Alexander transformed the relationship between the Egyptians and Hellenic peoples, particularly the Macedonians. Previously Greeks just had a trading colony in Egypt. In 332 BC they suddenly became colonists in a country thousands of years older than their own city states and lands. The Macedonian Greek rulers from 323-30 BC were known as the Ptolemies, after Alexander's general and next ruler of Egypt Ptolemy I Soter. The Ptolemaic period has been regarded as decadent and, beyond a few writers and scientists from Alexandria, worthy of little comment. An attitude reflected in the 1980s BBC television series The Cleopatras, which depicted the Ptolemies as murderous and sexobsessed (despite this, the series was a flop!). Exhibitions in Amsterdam (Allard Pierson and Hermitage), in Madrid and Oxford (Ashmolean Museum) in 2011 have reappraised the history of the Macedonian Kingdom, Alexander the Great and his legacy, reflecting more nuanced recent scholarship and interest in this area. Written evidence, letters on papyrus for example, and visual culture show incomplete but compelling stories of the impact of historical events on peoples, both Greek and Egyptian, rather than formal histories. This trail concentrates on objects in the Petrie Museum that highlight parts of the long relationship between Egypt, Egyptians and their Hellenic neighbours, and Alexander the Great himself. The images in this trail are either of objects in the collection not normally on display in the museum or from relevant external sources. Greeks in Egypt before Alexander 1 Mycenean IIIB1 stirrup vase of pottery found at Gurob. UC16631. Period: Late Dynasty 18 (1550-1295BC). Connections with the Bronze Age Greeks from Mycene have been found through pottery and other products in Egypt. Fragments of Mycenean pottery were found at the palace site of Gurob, where foreign princesses who married into the Egyptian royal family resided. 'IIIB1' is an archaeological term used to refer to different periods of Mycenaean history. 2 A fragment of red figure attic ware pottery found at Naukratis. UC19358. Period: Early Fifth Century BC. Pottery Room Display Case PC34. Black polished Attic-ware pottery sherd with laurel crowned head. Page 3 of 12 Naukratis was the only Greek colony in Egypt, founded under the 26th Dynasty (664-525 BC) and acted as a trading post for the Greeks in Egypt. There are many references to it in antiquity. The Greek historian Herodotus refered to the town, mentioning that the brother of the Greek poetess Sappho lived there and fell in love with a courtesan. Petrie excavated the site in 1884-5. See also 2b. Figurine in Case IC19, UC16469. This statuette shows an 'archaic' style Greek statuette heavily influenced by Egyptian sculpture and wearing an Egyptian type loincloth. Compare this to some sculptures from the same period - these archaic sculptures from Delphi in Greece. Koros from the late Sixth Century inDelphi Museum, Greece. 3 Scales from Persian body armour. UC74787. Dynasty 27 or First Persian period (525–404BC). In Pottery Room, Display Case PC34. Two thousand iron scales from body armour, found by Petrie in a room by the court at the Palace of Apries at Memphis and dated by him to the Achaemenid Period; other parts of the same find were distributed to twelve other collections. At the time when the Greek historian Herodotus visited in the fifth century BC and when Alexander the Great conquered Egypt over one hundred years later, the country was ruled by the Persians as part of their huge empire. Page 4 of 12 The Persians ruled in Egypt in two periods: 525-404 BC and 341-33 2BC. The Persians were unpopular rulers. Herodotus reports the story of King Kambyses murdering the sacred Apis bull at Memphis. However, this story has been discounted by some scholars and the unpopularity was probably as much to do with brutality, high taxation and the disregard for the ‘priest-class’ of Egypt as well as religious differences. There had been uprisings against the Persians across the Empire from 420 BC onwards and in 404 BC Egypt regained independence and retained it for 60 years. The Persian king Artaxerxes III restored Egypt to the Empire, but Alexander the Great knew that the people of Egypt were dissatisfied with Persian rule and likely to back his army against the Persian King Darius III in 332BC. UC16136. A blue and white faience Persian tile found at Koptos and dating from Dynasty 27 or the first period of Persian rule (525-404 BC). Not on display. The Persians had their own distinctive style. The human headed sphinx on this faience tile was a popular motif in monumental art and often the head depicted the Persian king. Alexander the Great Alexander the Great of Macedonia invaded and conquered Egypt in 332 BC and paid homage to the Egyptian gods at Heliopolis and at Memphis, where he sacrificed to the Apis bull and held gymnastic games. Through this sacrifice and games, he laid claim to the title of Pharoah at Memphis (Thompson 1988, 106) and it is there that Macedonian Greek rule and the satrap Kelomenes was first based, despite the establishment of Alexandria in the north. After his death, his friend and companion Ptolemy stole Alexander’s body and buried him at Memphis in 332 BC. 4 Terracotta head possibly of Alexander the Great. UC49881. Ptolemaic Period (323 – 30BC) Main Room Display Case IC19 (at end of Stonework: Inscriptions and Stonework Statuary). Page 5 of 12 Fragment of a hollow man-made terracotta, manufactured in two halves, the back is unmodelled. The subject is an identical portrait type with shoulder length, wavy hair and possibly represents Alexander the Great. It is not definite that this terracotta head depicts Alexander. Although the leonine hair, the eyes slightly heavenward, inclined neck, the soft features and smooth chin are all key features of portraits of Alexander the Great. Greek portraiture was both idealising and realistic and, similarly to Egyptian portraiture, certain features were emphasised to express permanent values (Stewart 1993, 66). Alexander is always presented as an athletic and youthful man. This image is based on one made by the Greek sculptor Lysippos in Alexander’s lifetime. Lysippos is thought to have crafted Alexander’s physical faults, a dropping neck for example, and unusual choices about being clean shaven, unusual for a Greek man beyond his mid 20s, into an identifiable and charismatic portrait. On the left a portrait of Alexander found at his birth place Pella in Macedonia, Greece. On the right a relief of Alexander as Pharaoh at Luxor. Statuettes meant that sculptures could be copied and reach a ‘mass’ audience. Most of the statuettes of Alexander come from Egypt, but we do not know their function. Stewart suggests that they may have been used in private cults, emulating the official cults set up by the Ptolemies after Alexander’s death. Or they may have been tourist souvenirs or military talismans (Stewart 1993, 45). 5 Alexander as Heracles, plaster cast of relief from sard ring. UC31942. Ptolemaic Period?In Display Case IC19 (see above). Gems and cameos were another form of portraiture; showing profiles similar to those used on coins. Wealthy people may have them on rings or as amulets and as this tiny cast illustrates, the original is now lost, the ring had intricate and skillful modelling. Page 6 of 12 Alexander is shown wearing a lion skin in the style of Heracles, the legendary ancestor of the Macedonian royal family. This image symbolises more than dynastic power. Alexander is depicted as a semi-divine hero who became immortal; the inference is that Alexander shares the story of Heracles, not just his genes. Another depiction of Alexander on coins and medals was with rams’ horns as Zeus Ammon. Alexander visited the oracle of the hybrid god Zeus Ammon at Siwah in the western deserts of Egypt shortly before his final major battle with the Persians and his journey into the Eastern fringes of the Persian Empire and beyond. From this point Alexander claimed a close relationship with the god, bordering on declaring himself semi-divine. On the left is a medal of Alexander the Great with the rams horns as Zeus Ammon on display in the Art Institute, Chicago. On the right is a modern depiction of Alexander as Zeus Ammon in a water fountain at Nea Pella, Greece, near the site where he was born. How Greek were the Macedonians? Just how Greek the Macedonians were at the time of Alexander and before is a complex and controversial question. Many Greeks in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC did not consider the Macedonians to be truly Greek, due to cultural differences; for example not watering down wine, different dialects and political reasons. The ostentatious and glittering goods in the royal tombs of Vergina, seem to have more in common with Tutankhamen than the tombstones or cemetery urns of the Athenians. However, much of the ancient Greek attitude towards the Macedonians is derived from unfriendly speeches given by politicians in Athens, such as Demosthenes. The Heracles to Alexander exhibition at the Ashmolean in Oxford in 2011 explored how much the Macedonian Kingdom was influenced by their southern Hellenic neighboursin the centuries before Phillip II and Alexander in the Fourth century BC. Page 7 of 12 Alexander certainly considered himself to be Greek and had been taught by leading Greek philosophers and historians, including Aristotle at Mieza from 343 BC. He was known to carry a copy of the Iliad annotated by Aristotle. Alexander emulated the Homeric ideal and cast himself in the role of Achilles, not least in his relationship with his boyhood friend, lover and partner Hephaestion. Alexander framed his military campaign against the Persians as one of revenge for their invasion of Greece over one hundred years earlier and a cultural campaign of hellenisation. Today, there is a northern province or region called Macedonia within the modern state of Greece and a country known as the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, just to the north of this region of Greece. What constitutes Greece and Macedonia, and vice versa, is a live political issue not entirely resolved to this day. A cult depiction of Alexander’s companion Hephaestion. When Hephaestion died, Alexander asked the oracle at Siwah whether he should worshipped as a god or cult hero. The oracle answered a hero and a cult was established. Here Hephaestion receives wine from a young girl on a stele from Pella, capital city of Macedonia. The inscription reads ‘Diogenes to Hephaeston the hero’. Cultural Changes: Life and Death 6 Two handled drinking cup. UC19372.Ptolemaic Period (323-30BC) In Pottery Room Display Case PC34. The shape of this cup is Greek in style. After Alexander died on 10/11 June 323 BC, his empire was split with much bloodshed and acrimony between his Companions (elite group of friends and military commanders). Ptolemy I Soter took control of Egypt and Alexander’s body; bringing the dead ‘pharaoh’ to Memphis as a sign of his legitimate claim to the throne. Ptolemy later transferred Alexander’s body from Memphis to his capital Alexandria in 306 BC. Page 8 of 12 The life of the Macedonian Greeks amongst the Egyptians was at first separate and there was a conscious preservation of cultural identity and social status among the colonial elite. 7 Pottery ostracon (or sherds of pottery) listing names of individuals and the quantities of materials issued to them UC71101. Ptolemaic period. Pottery Room Display Case PC35 This ostracon is in demotic – a cursive version of the Egyptian language from the Greek word meaning ‘popular’ (demotikos). The Greek language was the main language of colonial power and administration in Macedonian ruled Egypt. Famously, Cleopatra VII, the last pharaoh, was the only Greek ruler to speak Egyptian. Fragments of letters and official documents on papyrus illustrate a gradual assimilation of Greek with Egyptian culture, though the aristocracy always preserved some cultural and linguistic distance. 8 Terracota medallion in shape of a Gorgon face. Found at Memphis and from the Ptolemaic period (305-30BC). Pottery Room Display Case PC 35 Terracotta medallion of a gorgon head; there are traces of white paint on the surface. The facial features are sharply moulded and the hair wavy with two entwined snakes at the top. Medusa heads were popular evil averting devices in antiquity. This medallion in the form of a gorgon, a woman with snakes for hair, is likely to be from a coffin case. It is very similar to a gold medallion of Medusa found in a tomb, likely to have been that of Philip II (Alexander’s father), in Vergina (Aegae). The Gorgon has links to the myths around Heracles and thus to the Macedonian royal family. 9 Cartonnage mask of papyrus base UC45850 Ptolemaic period Main Room Coffin Cases. One of the greatest differences between the Greeks and Egyptians was their attitude towards the treatment of the body after death. The Egyptians believed in preserving the body through mummification and retaining the identity of the person so that they could enter the afterlife. The Greeks had a tradition of cremating their dead, though personal identity could be maintained on stelai or other markers. Urns containing ashes of bodies have been found in Egypt but gradually Greek occupiers also practiced mummification and buried the remains in a similar way to the Egyptians, as this cartonnage mask illustrates. Page 9 of 12 Difference or Assimilation? Ptolemy I ruled Egypt and parts of eastern Libya after Alexander’s death when a settlement was made between Alexander’s former allies and commanders at Triparadeisos. Alexander’s empire had been divided unofficially into separate regions – Egypt, Macedon, ‘Asia’ (Asia Minor and the old Persian centre) and India. Ptolemy published his own history of the conquests in 320 BC, which stressed his closeness to Alexander (Stewart 1993, 229) and established the cult of Alexander in Egypt, particularly at Alexandria. The removal of Alexander’s body to Egypt and from Memphis to Alexandria was also used by Ptolemy to show that he was the true heir within Egypt. Silver Tetradrachm showing the head of Ptolemy I Soter (UC39202) . Ptolemy had the satrap of Egypt, Kleomenes, assassinated. There was a fiscal crisis in 321-20 BC, prompted in part by this assassination and Kleomenes’ extortion while in power. Ptolemy put in a massive outlay of money to get currency produced. This coin was produced posthumously, but is likely to indicate the use of silver tetrachmins to pay Greek mercenaries as it is Athenian in type but minted in Egypt (Lewis 2001, 21). 10 Loop handle of a lamp showing a bust of Serapis UC54426. Roman Period Room IC19 (Inscriptions Cases/Ptolemaic Display) Page 10 of 12 The cult of Serapis was a Greek adaptation of an old Egyptian cult, combining the bull cult of Apis with the Greek gods Zeus and Dionysos (two gods also important in Macedonia and traditionally the ancestors of Ptolemy’s family). Serapis was a healing god, god of the underworld and greatest of the gods. Ptolemy I established this cult to fuse Greek and Egyptian religious practice and combine elements of religion popular with the Egyptians and those of the growing Greek population in Egypt. The image of Serapis was similar to Zeus and often, as on this lamp, wore a modius, or measure of grain, decorated with a relief of olive trees.The centre of the cult was the Sarapeion in Memphis, which has been described as the centre for a life between two worlds: Greek and Egyptian (Thompson 1988, 213). Although the focus on the cult was in Egypt, the increased traffic of people and goods between Greece and Egypt meant that other sites dedicated to the god have been found across the Hellenic world. For example, the sacred site of Dion, at the foot of Mount Olympos, and Phillippoi, a major city in Macedonia, have shrines to and depictions of Serapis as well as of Isis and other Egyptian gods and cults. The cult continued in popularity during the Roman period and meant that cult images were spread across the empire, even into Britain. 11 Daily life or religious votives? Limestone figures UC35954, UC75914 and a terracotta 35953. Main Room, Case WEC8, next to the Object by Site: Hawara Case. UC35954: Limestone group composition of four figures consisting of male figure with sidelock and pleated garment, head on pillow, and lying on his back. On top of him a nude female figure, whose face, now broken, in front view. At their feet a second male figure kneeling. On reverse side, rectangular box supports left knee of woman, and to left fourth figure of child with sidelock. UC75914: Limestone figurine of naked woman, short hairstyle, phallus tip visible towards vagina; remnants of pigment. UC35953: Red terracotta plaque - male figure to left; female figure to right with face in three-quarter view, nestling on his lap. She nurses child standing on her left knee These various figures may depict daily life and the traditions of depicting every day scenes, including erotic ones, in Greek art and crafts, such as those found on Greek vases from the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC. They may have been used as decorative objects in the home. They probably also have a religious significance and may have been used as votive offerings (Bailey 2008, 142 and 134). Page 11 of 12 Sexual mores, or at least the depiction of them, changed in Greek controlled Egypt. Dominic Montserrat has pointed out that a new body culture and representation of the body (particularly the naked body, both male and female) was established in Egypt under the Ptolemies. Sexual behaviour was a result of individual choice as well as established cultural practice (Montserrat 1996, 18). The Greeks, and then the Romans, depicted sexual activity in a frank manner. However, this does not mean that they did not have codes about sex. The potential use of these objects in religious rituals or as votives may be hard to comprehend. Sexual acts between people may not change much over 2,000 years, but cultural attitudes and representations always do! 12 Various figures and objects from Ptolemaic Egypt Return to the IC19, the case at the end of the Stonework: Inscriptions and Stonework: Statuary aisle. This display was put together by Sally-Ann Ashton to illustrate important figures and styles from Ptolemaic Egypt (Fitzwilliam, Cambridge). Alexander the Great and his political successor Ptolemy I were the beginning of over 300 years of Greek Macedonian rule in Egypt; rule that had an impact on Greece as well as on the people and culture of Egypt. Bibliography Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam (2010), Alexander the Great – Greeks in Egypt. Exhibition Catalogue. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (2011), Heracles to Alexander the Great. Treasures from the Royal Capital of Macedon. A Hellenic Kingdom in the Age of Democracy. Donald M. Bailey (2008), Catalogue of Terracottas in the British Museum. Volume IV. Ptolemaic and Roman Terracottas from Egypt John Boardman (1980), The Greeks Overseas. Their Early Colonies and Trade Paul Cartledge (2004), Alexander the Great. The Hunt for a New Past. Robin Lane Fox, (2004 repr.), Alexander the Great N. G. L. Hammond (1989), The Macedonian State: Origins, Institutions and History Tom Holland (2005), Persian Fire. The First World Empire and the Battle for the West Hermitage Museum (2010), The Immortal Alexander the Great. The myth, the reality, his journey, his legacy. Exhibition Catalogue. Naphtali Lewis (2001), Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt. Case Studies in the Social History of the Hellenic World Dominic Montserrat (1996), Sex and Society in Graeco-Roman Egypt. Claude Mossé (2001), Alexander. Destiny and Myth Andrew Stewart (1993), Faces of Power. Alexander’s Image and Hellenistic Politics Dorothy J. Thompson (1988), Memphis under the Ptolemies Julia Vokotopoulou (ed.) (1993), Greek Civilization. Macedonia Kingdom of Alexander the Great Michael Wood (2004), In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great. A Journey from Greece to India Thanks to my own intrepid companions in Macedonia during January 2011 and John J. Johnston and Carolyn Perry for their help. Page 12 of 12