10 1 9

advertisement

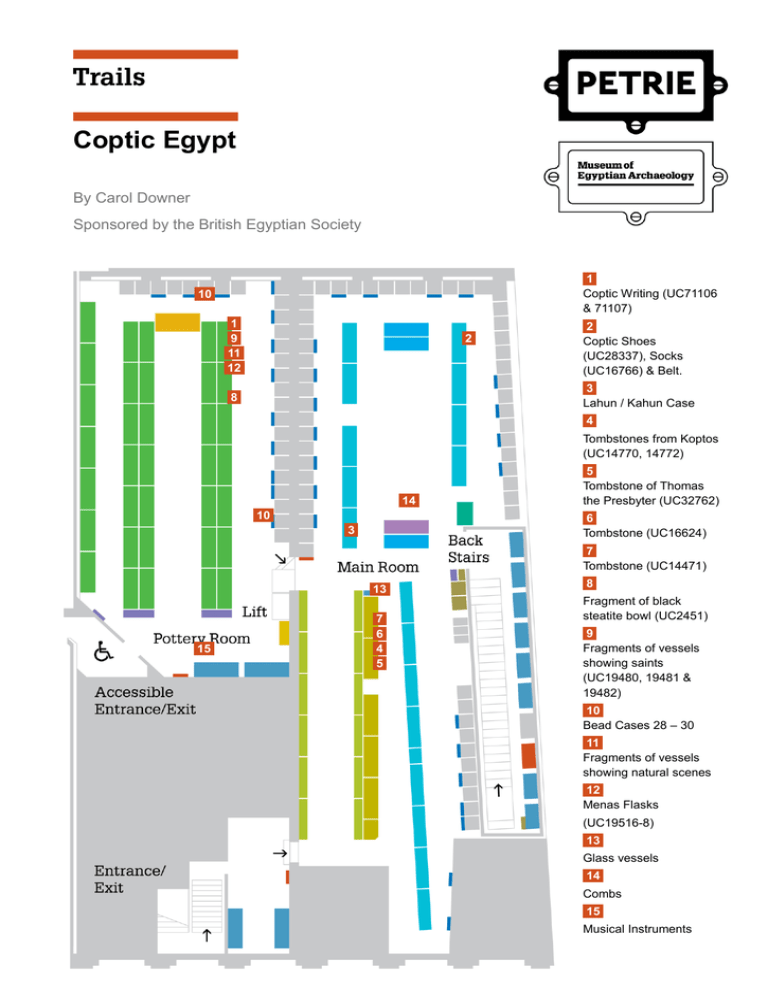

Coptic Egypt By Carol Downer Sponsored by the British Egyptian Society 1 Coptic Writing (UC71106 & 71107) 10 1 9 11 12 2 2 Coptic Shoes (UC28337), Socks (UC16766) & Belt. 3 Lahun / Kahun Case 8 4 Tombstones from Koptos (UC14770, 14772) 14 10 5 Tombstone of Thomas the Presbyter (UC32762) 6 Tombstone (UC16624) 3 7 Tombstone (UC14471) 13 15 7 6 4 5 8 Fragment of black steatite bowl (UC2451) 9 Fragments of vessels showing saints (UC19480, 19481 & 19482) 10 Bead Cases 28 – 30 11 Fragments of vessels showing natural scenes 12 Menas Flasks (UC19516-8) 13 Glass vessels 14 Combs 15 Musical Instruments It is frequently suggested that Ancient Egypt reached its demise long before what is now called the Coptic Period. However, this trail emphasises the continuity of culture and ideas from Pharaonic and Graeco-Roman into Christian Egypt, as well as the obvious change and innovation which occurred, particularly in religious affairs. Margaret Murray long ago wrote ‘the Coptic period is the Cinderella of Egyptological Studies’ (Ancient Egypt and the Near East 1935) It is to be hoped that, with the renewed interest in Late Antiquity across all disciplines, this attitude may be changing. What does the word ‘Coptic’ mean to us? The word Copt is derived from the Greek ‘Aigyptios’ via the Arabic Qibti. The original Greek may itself be a corruption of ḥwt ka Ptah, the name of one of Ptah’s Memphite shrines, meaning the ‘house of the spirit of Ptah’. When the Arabs invaded the country in the 7th century AD, they called Egypt ‘dar al-Qibt’ or ‘home of the Egyptians’. At that point the Egyptian people were Christian and so the name became associated with Egyptian Christianity and the Coptic Orthodox Church in particular. Originally the word simply meant Egyptian, and later became associated with its Christian people, their culture, liturgy, art, and language. To the Copts themselves, their name implies their own direct continuity with the pharaonic peoples. Early History The Coptic script and language after its development early in our era continued in use by the Christian population at least till the 13th century, despite the coming of Islam and the gradual adoption of Arabic. There were at least five main dialects and various subdialects of the language making about fourteen in all. The Sahidic or southern dialect of the language was the classical one, widely used in all areas and periods, but the northern Memphitic or Bohairic dialect was that adopted by the Coptic Church. This dialect is still used in the Church’s Liturgy today. Some families and local areas have endeavoured not to let the language die by using it in their homes and shops, both in Egypt and abroad. Nowadays there is also an international effort to modernise the language and to create new vocabulary. Coptic is the last stage of Ancient Egyptian, written in Greek script with six or seven borrowed demotic Egyptian letters, the classical dialect borrowing only six letters, whilst Bohairic found the need for seven letters (http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/writing/coptic.html). Bohairic is still used in the liturgy of the Coptic Church today. Page 2 of 16 After Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt at the end of the fourth century BC and the establishment of the Macedonian Greek administration under his successors, the Ptolemies, there was an obvious need to communicate with the indigenous peoples. There had been Greeks in Egypt for many centuries before that, first as traders and workers, and then as settlers, with colonies such as Naucratis in the Delta founded in the mid-7th century BC. However, the first extant attempts at writing Egyptian in Greek letters can be found only from the 2nd century BC. Even when the Romans gained control of Egypt after Octavian’s victory over Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31BC, Greek continued to be used for administrative purposes. From the 1st and 2nd centuries AD we find examples of ‘Old Coptic’, the vernacular written in the Greek alphabet, with borrowed demotic Egyptian letters. As this was initially used for non-Christian purposes, mainly in the realm of popular religion, in order to invoke a plethora of deities for health or protection whose names had to be written accurately lest their help not be forthcoming, far more Egyptian letters were needed than those that became standard later. We possess one or two invocations from this early period, but many later amulets and objects of daily life reflect a melting-pot of beliefs. In addition, despite the coming of Christianity, people still had recourse to magic, and used prayers that resembled the ancient ones even if the names now included those of the archangels. The Petrie Museum possesses a skull possibly from as late as the 7th century AD inscribed in Coptic, calling upon gods, angels and spirits from pagan, Jewish and Christian beliefs, including Sabaoth and the archangel Michael, always extremely popular in invocations (Montserrat, 2000: 23). Unfortunately it is too delicate to display. The gospel of St. Matthew Ch.2 tells us that the Holy Family sought refuge from Herod in Egypt and that Jesus spent his very early years there. The places where they are said to have stayed have become sites of pilgrimage and great devotion. The Apostle Mark is believed to have brought the Christian Gospel to Egypt, and to have been martyred there in 68 AD. Traditionally, St. Mark’s first convert was an Alexandrian shoemaker and Apollos, a citizen of Alexandria, is mentioned in Acts Ch.18. There is a tradition too that St. Peter may have visited Egypt. It is at the end of the 2nd century, with the bishop Demetrius, that we are on firmer ground as regards evidence. Around this time the famous Catechetical School, perhaps intended to supplant the ancient Museum, or university, was founded in Alexandria. Names associated with the School in the early days are Pantaenus, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen. Page 3 of 16 Books and Manuscripts The earliest attested New Testament text in Greek, part of St. John’s Gospel, the Rylands Papyrus from Bahasna in Middle Egypt, is usually dated to the late 1st or early 2nd century AD. From the 3rd century, there were apparently copies of books of both the Old and New Testament in the Upper Egyptian dialect. Budge’s Coptic Biblical Texts in the Dialect of Upper Egypt (BM 1912) is a manuscript of at latest mid-fourth century, and is perhaps the earliest papyrus Codex containing translations of books of the Old and New Testaments into Sahidic, suggesting that the texts from which they were copied were earlier still. It contains Deuteronomy, Jonah, Acts and the Apocalypse of John. The Petrie Museum has a number of manuscript fragments, including several that are probably from Deir Balyzeh (see below). UC 71006 is a fragment of parchment leaf with parts of two columns of Coptic from a sixthcentury Biblical manuscript preserving part of the Book of Kings. Later came hagiographic texts, lectionaries, homilies and spiritual treatises, too, which eventually found their way into many collections. The monasteries themselves had remarkable libraries, signs of which may still be found archaeologically. On all four walls of a room to the north of the apse of the great church in the White Monastery, there were traces of the titles of books, sometimes with the number of copies, from which Crum concluded that this was the monastery library. Many of the original manuscripts from this and other libraries may have been destroyed, but some were hidden in antiquity and rediscovered in modern times, subsequently finding their way into collections all over the world and many into the Coptic Patriarchate in Cairo (Lehnert and Landrock, 2000). The numerous fragments of Coptic manuscripts which Petrie retrieved from the clearance of Deir Balyzeh, south of Rifeh, were widely distributed, but the Petrie has some examples of manuscripts, such as this one pictured. Page 4 of 16 The online entry on ‘Groups of books in Coptic Egypt’ (http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/writing/library/coptic.html) shows the great variety of finds, including a papyrus brought back by Petrie from the Fayyum and now in the British Library which seems to record a list of at least 105 books, mainly Coptic but with some Greek, to which someone says he has added diacritical marks. Crum (1893) thought the list was the inventory of part of a library, for which he could only find one parallel at the time. The manuscripts seem to have been inscribed on leather material and papyrus paper. The Scriptoria of the Hamuli monastery in the Fayyum, from which many of the Pierpont Morgan manuscripts came, ceased functioning about the mid-tenth century; the latest dated colophon was in 946. 1 Examples of Coptic writing on ostraca. Pottery Room, Pottery Case 37, middle shelf. Many thousands of inscribed ostraca survive from ancient Egypt of which the Petrie holds a considerable number of Coptic examples, a few of which are on display. These give us insight into the preoccupations of monastic settlements and their surrounds. The two selected here have the advantage of being short UC 71106 (Crum Varia Coptica, no. 57) is a note about a tailor’s payment. ‘Staurogram: Concerning the garment you have made for me, I have paid you six measures, which makes a gold termesion (tremis)’. Sadly, there is no mention of the type of garment indicated here. Many examples of garments from the Coptic period do survive, however, but obviously vary depending on context. At the Monastery of Epiphanius near Thebes, monks’ burial garments were found. In this area near Thebes, too, many of the ostraca and papyri edited and indexed by Crum (1921) were also found, relating to many varied aspects of everyday life. UC 71107 in the same case relates to a consignment of wine and is in the same hand and Middle Egyptian dialect as others in a group (Nos. 500-510) once belonging to Petrie and published by Crum in Coptic Ostraca (1902). Several of these mention a certain Thomas the deacon giving orders for skeue (of wine) to be given to various people or sent to different places, in one case at least to the area of Oxyrhynchus, much further north. No. 502, displayed here, mentions his giving two skeue to Peti (though this may not be a name but only mean ‘the person who comes’) and to a certain Isaac, and a quantity of grapes too. In Crum’s view, although this group of ostraca appears to have been found near Thebes, it may have originated elsewhere. Page 5 of 16 Textiles 2 The Coptic Socks of c.400-500 AD, UC 16766. Main Room, Hawara Case, right-hand side towards the bottom. These socks became well-known through the project which the museum ran in 2009-10 to recreate Ancient Egyptian two-toed socks (Booth 2011) using ancient techniques and providing a pattern to help others make them. Also look out for the shoes (UC28337) and belt (UC280881). They are well worth a visit as are the many other small objects of daily life in the same and the adjacent case. Examples of embroidery are exceptionally bright and give insight into the fine craftsmanship of the period. The Petrie’s own pieces are too delicate to display, but the following photographs give an indication, while the Victoria and Albert Museum has an extensive collection for further study, showing the continuity of classical motifs with its ‘loves and cupids’ (male and female putti figures), rural scenes with men hunting and fishing, and Christian scenes with military saints. The religious significance of Dionysus in scenes of grape-harvest and of other classical deities was probably lost, since such depictions were evidently not thought unsuitable for the predominantly Christian population. Designs may have been influenced from elsewhere since at the port of Berenice, for instance, an example of Chinese embroidery was found in an imported consignment. Fragments of Coptic Textiles UC6994 and UC6993. Page 6 of 16 UC6992 and UC6991. Monasticism The origins of monasticism are mysterious but it seems likely that even in New Testament times some chose to live celibate lives, though not necessarily apart from their families. The Alexandrian Jewish philosopher, Philo, describes a strange group called the Therapeutae who lived a communal life near L. Mareotis, which Eusebius, the Church historian, was convinced was an early form of Christian monastic community. The Essenes, too, perhaps the people of Qumran and of the Dead Sea Scrolls, were once thought to have lived a monastic life, though latest explorations suggest Qumran was more like a university, whilst a re-reading of Philo makes Eusebius’ proposition about the Therapeutae seem dubious in the light of our present knowledge. St. Antony is famed as the father of monasticism, but he was born into a world where people were already living a life of prayer in or near their villages. He organised those who gathered round him into small communities, but in due course himself withdrew deep into the desert to live a more solitary life, only occasionally visiting his followers to give them support. He also went to the Wadi Natrun to encourage new foundations there. In time the Egyptian monks made the ‘desert a city’ as St Athanasius says. From the Bohairic and Greek Lives of Pachomius, UC 59490, founder of Coenobitic monasticism, it seems that the Egyptian monks themselves believed they were in the desert tradition of Elijah, Elisha and John the Baptist, and thus probably wore a goatskin as part of their habit (cf. Hebrews 12). The author of the Historia Monachorum in Aegypto, an account of the visit of seven monks from Palestine to the monasteries of Egypt in 394 AD, tells us that the bishop of Oxyrhynchus believed there were by then 10,000 monks, and twice as many nuns, under his jurisdiction. The visitors generally found a varied situation, with the monks in the Wadi Natrun and elsewhere living a semi-eremetic life, and others a more or less autonomous life, while at the Pachomian monasteries they lived together in community. Page 7 of 16 With all these great heroes and heroines of the desert, for there were also women’s foundations and famous female ascetics like St. Syncletica, it is no wonder that Egypt became a centre for pilgrimage to living saints. In the fourth to the fifth centuries there were also great religious writers such as Pachomius himself, and his followers, and St. Paul of Tamma, as well as Shenoute, founder of the White Monastery (http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/athribis/monastery.html) and those who collected and wrote down the reminiscences of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers (Apophthegmata Patrum). Many Coptic objects of daily life from Athribis are displayed on this web-site. Flinders Petrie worked at several monastic sites which are represented in the Museum, including Deir Balyzeh near Rifeh in 1907, but seems to have collected only surface finds. There are many objects of daily life from 3 Lahun (Kahun) too, which may have come from the monastery at the site or the cemeteries, although sadly Petrie did not record details of the monastic buildings there either. Petrie remarked that it was hard to decide whether some objects should be dated to the Middle Kingdom or later periods, which is worth bearing in mind when looking at such inventions as the socalled rat-trap (UC16773) in the Kahun case. Many such objects must indeed have altered little over the millennia. C.C.Walter published an innovative book on Monastic Archaeology in 1974, and Peter Grossman has done much careful recording of architectural details at many monastic sites. In addition, there have been the amazing projects of preservation and restoration of wallpaintings at various monasteries carried out by the American Research Centre in Egypt with funding from the United States Agency for International Development, and managed by Michael Jones. These have produced volumes such as Monastic Visions (Bolman 2003) about St. Antony’s Monastery and The Cave Church of Paul the Hermit (Lyster 2008) on St. Paul’s Monastery. The team is at present also finishing work at the Red Monastery, where remarkable early wall paintings have been uncovered, and have worked at the White Monastery, where Stephen Davis is now active. 4 Monumental Tombstones Stonework: Statuary IC16 Middle and lower shelves. The case contains a series of tombstones from Koptos: nos. 14770, 14771, 14772, 14773.. UC14773 mentions one Apa Victor (Victor was a very famous military martyr in the third or fourth century, and so the name Victor became extremely popular from then on). Page 8 of 16 UC16798 This particular stone may be a shop-ready piece as it is prepared as though for inscription, though still blank. It is noted here because of the confronted birds which were a very frequent device in the Near East and continued to be used into the Byzantine period and beyond. M581 Doves, though they are actually labelled ‘eagles’. The hero between two beasts can be traced to the predynastic period in Egypt and Egyptian art with its reversible script incorporated into monumental design round doorways has always favoured such confrontation. It is also popular in Coptic manuscripts: M581 (from the Morgan Library in NY, originally found at Hamouli in the Fayyum), for instance, has doves facing each other on the headpiece (see above). Compare this image of a splendid 9th century BC pendant from Knossos, incorporating a ‘cross’ design with pairs of birds in upper and lower quadrants, next to an 8th century BC quiver with the ‘master of the beasts’ design. From John Boardman (1999), The Greeks Overseas. Page 9 of 16 Jill Kamil (2002: 163-4) has argued that the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove at Christ’s baptism is an Egyptian ba bird in origin, since she claims this is the only religion where one would find a bird in connection with spirit. In fact we do find the raven and then the dove with the olive branch in Genesis 8, 6-12, perhaps expressing reconciliation after the flood, and in Gen.1,1 the ruah or spirit of God hovering over the waters, so that the two ideas might very easily be linked. 5 UC32762 commemorates Thomas the Presbyter. The inscription probably reads “Jesus Christ. The Grace of God. The day of making mourning for our blessed brother Thomas, the priest. He went to his rest on 26 Khoiak in the first indiction [Byzantine calenrical cycle]. 6 Several other of the Petrie Coptic tombstones are inscribed, one belonging to Plemshpse or Plemshes UC16625, one to Wenobe the chosen, another, UC16624, to a monk and deacon called Origen. In some cases the design is strangely stylised and oriental-looking, like the bearded Christ or orans figure in 7 UC14471. Comparable in style to this is a lion’s head in the store of the BM, perhaps from the Monastery of Apa Jeremias, though attributed to Hagr Edfu, which is very similar to the lion head, UC75643, though even more stylised. Crosses and Conches In Treasures of Coptic Art in the Coptic Museum 2007, Gawdat Gabra illustrates the tombstone of one Petros, dated to the sixth century, Inv. No. 7730, with a central staurogram in the upper register below a pediment, flanked by the crux ansata on both sides, with a boat in the lower half having its sail in the form of a chi rho or christogram, the oldest Christian symbol. Three forms of cross or Christian symbol are thus used at once. The boat itself was used in funerary contexts in pharaonic times, so also displays continuity. A depiction of the Virgin Mary in the BM shows her with the crux ansata in one hand and a traditional cross in the other: perhaps the artist was attempting to make the same point about continuity. The Egyptian amuletic ankh symbol was adopted as a cross (known as the crux ansata or cross with a handle), particularly in funerary stelae and carved decoration, but it was used alongside, not instead of, the more traditional cross. It also adopts a new form more reminiscent of angelwings Page 10 of 16 Unfortunately the Petrie has no examples on display of monumental stones with the ankh or crux ansata, unless UC16798 above has damaged ankh signs beneath the arch, which seems unlikely. Most of the stones in the Petrie have traditional crosses of different styles: cf. the crosses above the hands of the figure in UC 14771 (see above) with those above the conch in UC2373. It has been suggested by Gawdat Gabra (2007: 27) that the shell itself, so popular in classical antiquity because of its association with Aphrodite rising from the waves, acquires the symbolism of Baptism in the bath of regeneration or of the Resurrection of Christ in the Christian period. The stele of Abba George, Bishop of Qasr Ibrim, UC2373, in the same case, of the 10th-11th century AD, written in Greek, also exhibits a crudely depicted conch. The shell is very popular in architecture particularly because it fits so neatly into apses or niches over doorways and continued in use both in churches and on tombstones for many centuries. From the 5th / 6th century church at Denderah. Military Saints and Martyrdom Many of the most honoured Coptic saints were military martyrs, the majority of whom suffered in what is known as the Great Persecution, inaugurated under the emperor Diocletian who came to the throne in 284AD. So strong is this era in the Coptic psyche that their own dating system begins in this year and is distinguished from the years of our modern era by prefixing AM for the Age of the Martyrs to their dates: thus AM 332 would actually be, by inclusive reckoning, 615 AD or CE. Eusebius in Book VIII of his Ecclesiastical History mentions the many Egyptian Christians who willingly went to their deaths rather than sacrifice to the genius of the Emperor. Page 11 of 16 We may think of St. George (Mar Guirgis) as the dragon-slayer par excellence, but there were many others - as depicted on the walls of the Monastery Church at St. Antony’s on the Red Sea. St. Mercurius (Abu Seifein) is another of these, with a huge cult in Egypt, as are St. Theodore, Claudius and Victor. Frequently the saint is shown mounted with his lance poised above the source of evil, often depicted as a human person (like Julian the Apostate), sometimes as a serpent (which the Greek word drakon means), and sometimes as a dragon with feet. The precedent for the latter in Egypt was undoubtedly the Nile crocodile, which in Pharaonic times might represent the forces of chaos and danger for very obvious reasons, with Horus shown standing triumphant over him, as he was also over the hippopotamus. In the classical period Horus is frequently shown as falcon-headed in Roman armour, again mounted, since as soldier and horseman he would still represent the restoration of maat or divine balance in the empire. There is a famous depiction of this in the Louvre, see below, and a similar tiny one, again of Roman period, in the Petrie in relief on the interior of a black steatite bowl 8, UC2451. UC2451 against a background of scallop shells, with a flat rim incised with what may be an olive design: the exterior possibly shows a dromedary in the right hand compartment. And example from the Louvre. A similar image of the mounted saint or martyr is evidently borrowed in the Christian period to represent the triumph of Christ (of whom the saint is a champion) over evil, whatever its manifestation. Because many such martyrs were men of high rank, often in the emperor’s or governor’s entourage, and so had to abandon their military oath to avoid sacrificing, they were shown as ‘knights’ on horseback. In fact, in Constantinople in the mid-fourth century a school of tribuni et notarii was founded to educate young men of high rank in the imperial civil service and these were given nominal military rank. Page 12 of 16 It is interesting that one of the earliest depictions of St George, who is always called a tribune in Coptic sources, which comes from St. Katherine’s Monastery and is of the 6th century, shows the saint in civil not military dress. M581, the manuscript with the confronted birds mentioned above, has a fine frontispiece of St. Pteleme, another military saint with much in common with St. George, this time meeting a saintly ascetic called Papnoute. He is called both tribune and notarios in the text. 9 Fragments of vessels UC 19480, 19481 and 19482. UC 19481 Pottery Room PC37 One can see several fragments of vessels in the pottery case showing images of unnamed mounted saints, sometimes with the vessels’ owners also, who were presumably seeking the saints’ protection. UC19481 is also interesting in having the woman’s face partly moulded, with her nose used as a kind of handle. This also depicts seated ecclesiastical figures in vestments, and figures of fish or birds. The woman is wearing an elaborate earring; it seems that despite the strictures of St. Paul, Christian women continued to wear jewellery. 10. Examples from Illahun and Qau can be found in the bead cases very close to the pottery (BC 28-30). Some is specifically Coptic, some of Roman period, but of course Roman design and technique would have continued in use. 11 Pottery fragments with crosses and naturalistic scenes. Some pottery fragments are decorated with crosses, whilst many of them depict naturalistic scenes. There are palm trees in their bedding pots UC19508 (as Hatshepsut’s brought from Punt at Deir el Bahri), and more fish and birds, one perhaps a cock, UC19497. UC19500 displays a rather cross-eyed fish, and UC19496 has two birds fighting over a worm. What looks rather like a comb at their feet is perhaps a discarded fish skeleton or a ‘centipede’, as Margaret Murray suggests, but with only 16 legs. There are also secular figured scenes such as UC19487 and UC19488, perhaps intended to depict the popular ‘pygmies’. Page 13 of 16 Some pottery is plainer, such as the examples from the fifth-century hermitage which Lady Petrie published in Petrie’s Tombs of the Courtiers. Here, however, the walls were decorated, for instance with an early example of confronted unicorns on either side of a cross, a very popular subject in monks’ cells and in churches because of the association of the unicorn with the incarnation and the unity of the Godhead. Manuscripts also displayed unicorns, probably for the same reason, such as the example from M581 (not illustrated). 12 Menas Flasks Pottery Room PC37, at the back of the middle shelves The fragmentary manuscript UC62835 (not on display) mentions the transport of six litrai (presumably of water!) for the camels, as well as 200 diplai of wine for the town. Camels were very well used in all situations by the time monasticism became established. St Antony when he first went to his retreat near the Red Sea had camel caravans bringing him supplies at least twice a year. Numerous papyri from Oxyrhynchus and elsewhere mention the toll-taxes applied to camel loads as they travel to the oases and elsewhere. Although dromedaries were certainly known and perhaps occasionally used in Egypt in the early first millennium BC or earlier (the mandible of a camel was found in a domestic context of the 10th century BC at Qasr Ibrim), their more extensive use follows the Persian period and later the coming of the Greeks and Romans. Camels are frequently depicted in the St. Menas flasks associated with pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Menas at the monastery which grew up at his topos or shrine on the shores of L. Mareotis near Alexandria. There are examples of flasks in the pottery cabinet UC19516-8. St Menas, according to one version of the legend, was of Egyptian origin, but did military service in Phrygia, where he was martyred. His fellow soldiers brought his body home as a relic, its presence on board ship affording protection against long-necked sea monsters. The men then employed dromedaries to take the body home on arrival in Egypt, but these stopped dead on the site where his monastery was later built, and refused to go further, indicating divine will over the choice of site. It is thus disputed whether the creatures on the flask are the sea monsters or camels, or one of each! 13 Glass Main Room, Glasswork case There are fine examples of Roman and Coptic period glassware in the glass cabinet, and also at the bottom of WEC 10 where the socks are displayed. 14 Combs Main Room, Near the Amarna / Mummy Portrait Case Page 14 of 16 On special display are the Ancient Egyptian combs, which include several Coptic examples. 15 Musical Instruments. Pottery Room, Case. There are examples of musical instruments which doubtless continued in use into the Coptic period, scattered throughout the museum, such as the bronze sistrum, UC35791, including the model of a monkey or baboon with a flute, UC59262. The Coptic Liturgy does not use instruments other than cymbals and the triangle, however, which are apparently employed to attract attention to the prayers of the congregation. Coptic chant is very ancient; until very recently it was only handed down orally but has still been preserved for centuries in this way. Much work has been done in recent years to locate and record the Coptic musical repertoire as accurately as possible, and to transcribe it into notation. Through the Institute for Coptic Studies which was founded in 1955, Ragheb Moftah saw to the recording of the repertoire of the great blind cantor, Mikhail Girguis, and then a recording of St. Basil’s Liturgy was made. Late in his life Moftah donated all his recordings to the Library of Congress, and their librarian Marian Robertson-Wilson collated these recordings and produced in 1997 the Guide to the Ragheb Moftah collection of Coptic Chant, which was revised in 2005 to be used with 21 CD’s. The earlier history of research on Coptic music was published by Brill in a useful survey done by John Gillespie in Future of Coptic Studies 1978 (available online). Icons Although the Petrie museum does not itself show/own any Coptic icons, icons play an extremely important part in Coptic church and home life, and must not be forgotten. As it has often been remarked that there is a similarity between Coptic iconography and the mummy portraits from Hawara or elsewhere, and possibly an influence of the latter on Coptic art, it is worth looking at the case of mummy portraits separating the two halves of the top gallery. Similar techniques may well have been used initially although Coptic iconography has its own distinct naïve look and proportions. Zuzana Skalova and Gawdat Gabra’s book Icons of the Nile Valley published in 2001 covers the different phases and developments of Coptic Art and later influences. Brief Bibliography Adams, W.Y.(1996) Qasr Ibrim - The Late Mediaeval Period. London: Egypt Exploration Society. Boardman, John (1999) The Greeks Overseas: Their early Colonies and Trade, London: Thames and Hudson. Page 15 of 16 Bolman, E.S., ed. (2002), Monastic Visions. Wall Paintings in the Monastery of St. Antony at the Red Sea London: Yale University Press. Crum,Walter (1893), Coptic manuscripts brought from the Fayyum by W M Flinders Petrie London Digital Egypt Website: http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/ Depuydt, Leo (1993), Catalogue of Coptic Manuscripts in the Pierpont Morgan Library, with Album of Photographic Plates by David A. Loggie, Leuven: U. Peeters. Gabra, Gawdat (2002), Coptic Monasteries: Egypt’s Monastic Art and Architecture, with a historical overview by Tim Vivian. London: American University in Cairo. (2007) The Treasures of Coptic Art in the Coptic Museum and Churches of Old Cairo Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press. Griggs, C.Wilfred (1993), Early Egyptian Christianity from its origins to 451C.E, Leiden, New York, Köln: E.J.Brill. Grossmann, Peter (1986), Abu Mina - A guide to the Ancient Pilgrimage Centre, Cairo, Fotiadis and Co. Press (2002) Christliche Architektur in Ägypten. Leiden, Boston and Cologne: E. J. Brill. Kamil, Jill (2002) Christianity in the Land of the Pharaohs: The Coptic Orthodox Church, London: Routledge. Lehnert and Landrock (2000) Illustrations from Coptic Manuscripts, Cairo, Egypt Lehnert and Landrock (1998), Coptic Icons I and II, Cairo: Egypt Lyster, William, ed. (2008), The Cave Church of Paul the Hermit at the Monastery of St. Paul Egypt American Research Centre in Egypt, London: Yale University Press. Meinardus, Otto F.A. (1961 & 1989), The Monks and Monasteries of the Egyptian Deserts, American University in Cairo Press. (2002) Coptic Saints and Pilgrimages, American University in Cairo Press. Montserrat, Dominic (2000) Digging for Dreams (Treasures from the Petrie Museum).Glasgow City Council. Russell, N. (trans.) and Ward, B., SLG (Introduction) (1981), The Lives of the Desert Fathers: The Historia Monachorum in Aegypto, London and Oxford: Mowbray; Kalamazoo USA: Cistercian Studies series 34. Abbrev. HM. Walters, C.C. (1974), Monastic Archaeology in Egypt, Warminster: Aris and Phillips. This trail has been funded by the British Egyptian Society www.britishegyptiansociety.org.uk. Page 16 of 16