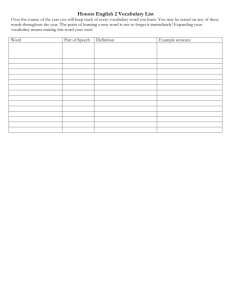

A L C

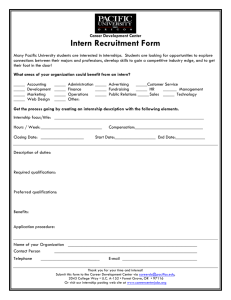

advertisement