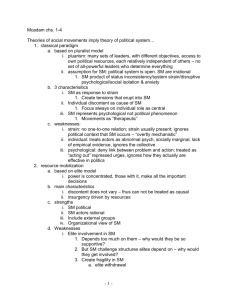

Under the Thumb of History? Political Institutions and the Please share

advertisement