Softly to the East By Rachel Claus Hector A PROJECT

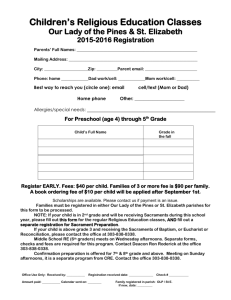

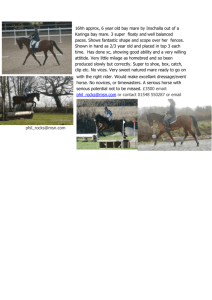

advertisement