Activity Booklet WISCONSIN FOREST TALES

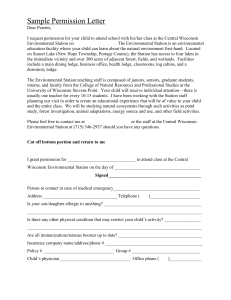

advertisement