Healing Ministry

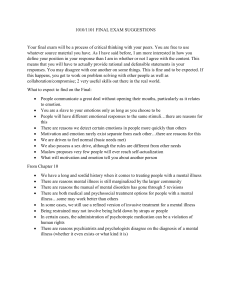

advertisement