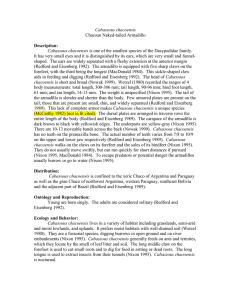

Katie Perryman Average head and body length 220-400mm Average tail length 90-175mm

advertisement

Katie Perryman Description: Average head and body length 220-400mm Average tail length 90-175mm Average weight 2.02kg The large hairy armadillo (Chateophractus villosus) is the largest armadillo in the genus Chateophractus (Redford and Eisenberg 1992). Like other armadillos it is covered in armor. The armor develops from skin and is made up of hard bony plates called scutes (MacDonald 2001). The carapace (armor) protects the shoulders, back, sides, and rump (Nowak 1999). The central portion of the armor is made up of about 18 bands, 7-8 of which are movable. In addition to the carapace, there is a shield on the head and between the ears. Some individuals in this species have 3-4 holes in the pelvic region of the armor that open to glandular pits (Redford and Eisenberg 1992). The large hairy armadillo, as the name suggests, has more hair than other armadillos. Hair projects from the scales of the armor, and whitish to light brown hairs cover the belly (Nowak 1999). C. villosus has 5 claws on the hind limbs and 3, 4, or 5 claws on the very powerful forelimbs. These animals have 14-18 teeth in each jaw (MacDonald 2001). C. villosus being a member of the dasypodidae family has simple oval teeth in cross section (Vizcaino et al 2004). They have poor eyesight, and well developed hearing (MacDonald 2001). Distribution: C. villosus is found in South America, from northern Paraguay, to the Gran Chaco of Bolivia to central Argentina (Redford and Eisenberg 1992). The large hairy armadillo is found in two national parks in Paraguay, the Defensores del Chaco in northern Paraguay and the Teniente Enciso in northwest Paraguay (Yahnke 1998). Ontogeny and Reproduction: Males and females of the species mate in September, but males have been observed mounting females in every month of the year (Redford and Eisenberg 1992). The males follow the females until they are ready to breed. Up to 1/3 of females will fail to breed each year. Lactating and pregnant females can be very aggressive (MacDonald 2001). Females build a nest by collecting leaves under their body and then kicking it behind them to form a mound. The females will growl at anything disturbing their nest site (Redford and Eisenberg 1992). They experience a 60-75 day gestation period. There is more than 1 litter annually. Usually fraternal twins are born, one male and one female (MacDonald 2001). Birth occurs from February to December (Redford and Eisenberg 1992). The young weigh 155 g at birth and open their eyes after 16-30 days. They are weaned at 50-60 days, and reach sexual maturity at 9 months (Nowak 1999). The young are active in the late morning or the early afternoon (MacDonald 2001). Ecology and Behavior: C. villosus is an omnivorous species (Machiote 2004). They eat mainly invertebrates. They move slowly along the ground with their nose in the soil or leaf litter. They dig up material and open rotten logs with their fore claws. These animals will burrow under and into carcasses to reach maggots (MacDonald 1999). They also consume plant matter, carrion, eggs, occasional snakes and lizards (MacDonald 2001). Some have been seen killing snakes by jumping on them and cutting them with the edge of their armor (Nixon 2004). C. villosus preys on Kelp gulls (Larus domnicanus) in Patagonia, Argentina (Borboroglu and Yorio 2003). The large hairy armadillo also preys on Imperial Cormorants (Phalacrocorax atriceps) and Rock Shags (Phalacrocorax magellanicus) in Patagonia, Argentina (Punta et al 2002). C. villosus is solitary except when rearing young or mating (Machiote 2004). These animals inhabit open areas in semi-desert conditions (Nowak 1999). C. villosus also inhabits desert, temperate grassland, and forest. They have an average home range or 3.4 hectares (Nixon 2004). They can tolerate very dry conditions (MacDonald 2001). These mammals have a low body temperature (24-35.2ºc) to conserve heat and moisture. They can also shiver to generate heat. They spend the coldest and hottest parts of the day underground. C. villosus shifts activity to forage in the warm mid-day or the cool and moist evening, but they are mostly nocturnal. The large hairy armadillo may have extensive burrow systems (MacDonald 2001). They occupy burrows for only short periods of time, and then move to a new one (Machicote 2004). The hairy armadillo is predated upon by canines, aves, and humans (Nixon 2004). When chased the hairy armadillo first tries to run away and may snarl. It tries to find a hole or will burrow into the ground to avoid predators. It anchors itself in its burrow by spreading its feet out sideways and bending its body so the hind edges of the bands cling to the burrow wall (Nowak 1999). If it can not outrun its pursuer, it withdraws its limbs under the carapace and sits as tightly to the ground as possible (MacDonald 1999). Remarks: The hairy armadillo can live 8-12 years in the wild. There are reports of them living up to 30 years in captivity (MacDonald 2001). Armadillos can become infected with leprosy. They exhibit no external symptoms until the disease has progressed significantly. It was first found in populations of armadillos in the 1970s. C. villosus is hunted by humans for food and because they cause damage to agricultural lands (Nixon 2004). The species has some unique features that make it coveted for biomedical research (Codon 1999). Also, it is the second most common armadillo found in zoos (Nixon 2004). Literature Cited: Borboroglu, Pablo Garcia and Pablo Yorio. 2003. Habitat requirements and selection by Kelp Gulls (Larus domnicanus) in central and northern Patagonia, Argentina. The Auk. Vol.121. No.1. Pages 243-252. Codon, S.M., Estecondo, S.G., Galindez, E.J., and Casanave, E.B. 1999. Ultrastructure and morphometry of ovarian follicles of the armadillo Chaetophractus villosus (mammalia, dasypodidae). Departmento de Biologia. Universidad Nacional del Sur, San Juan. MacDonald. David. Encyclopedia of Animals. 1999. Barnes and Noble Books. New York. Pages 796-798 MacDonald, Dr.David. Encyclopedia of Animals. 2001. Facts on File Inc. Andromeda Oxford Limited. Pages 281-283. Machicote, Marcela, Branch, Lyn C. & Villarreal, Diego. 2004. Burrowing owls and burrowing mammals: Are ecosystem engineers interchangeable as facilitators? Oikos.Vol 106. Issue3. Pages 527-535. Nixon, J. “Hairy Armadillos: Three Species” http://www.msu.edu/~nixonjos/armadillo/ Index.html?. Accessed 30 September 2004. Nowak, Ronald M. Walkers Mammals of the World. Sixth Edition. Vol 1. 1999. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore. Punta, Gabriel Pablo; Yorio Jose Saravia, and Pablo Garcia Borboroglu. Breeding Habitat requirements of the Imperial Comorant and Rock Shag in Central Patagonia, Argentina. 2002. Waterbirds. Vol.26. No.2. Pages 176-183. Redford, Kent and John Eisenberg. Mammals of the Neo-Tropics: The southern cone: Chile Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. 1992. Vol.2. University of Chicago Press. Pages 54-56. Vizcaino, Sergio and Gerardo De Luliis. 2003. Evidence for advanced carnivory in fossil armadillos: Mammalia Xenartha Dasypodidae. Paleobiology. Vol.29. No 1. Pages 123-128 Yahnke, Christopher Isabel Gamarra de Fox and Flavio Colman. Mammalian species Richness in Paraguay: The effectiveness of national parks in preserving Biodiversity.1998.Biological Conservation.Vol 84. No3. Pages 263-268 Reference written by Katie Perryman, Biology 378 student. Edited by Christopher Yahnke. Page last updated. http://www.fotosave.com.ar/FotosMamiferos/FotosEdentata.html