University of Saskatchewan School of Public Health Task Force Report

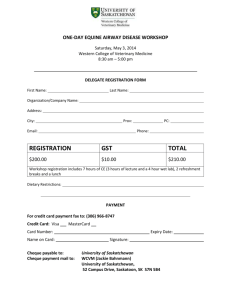

advertisement