Document 11990726

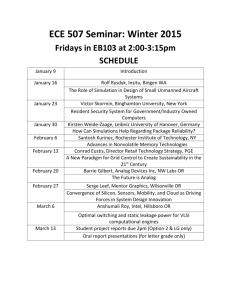

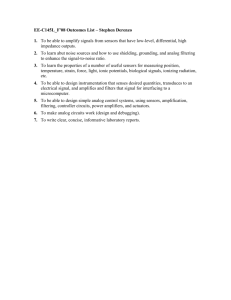

advertisement