How can comparative law profit from modern marketing? An answer... can be found in this book.

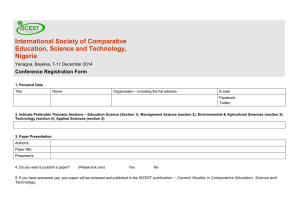

advertisement

How can comparative law profit from modern marketing? An answer to this question can be found in this book. In this book Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. mult. Markesinis, one of the most outstanding scholars in comparative law of our times with a 35-year long career in 25 universities on both sides of the Channel, explains to us how a market for the products of the study of comparative law can be created. He does so by putting forward the idea, well known in business, that the success of a product is also dependent on the attractiveness of its packaging. The comparatist must likewise take the raw material of ‘foreign law’ and make it sufficiently user-friendly so as to persuade the potential legal consumers – judges and lawyers – to use it in order to solve their legal problems. This method, developed and practised by the author, by which modern marketing techniques are transferred into the realm of justice, has already borne fruit in the caselaw of the British legal system and will, I am convinced, continue its triumphant procession outside Great Britain. The efforts of the author over the past decades to interpret French, German, and Italian law for legal practitioners in his homeland and to make decisions from these systems available to the English legal establishment have received their well-earned success. They have also received support from the new zeitgeist of globalisation. At the threshold of the 21st Century, the end of the Cold War, an immense increase in academic exchanges across national borders, an increase in the practical use of worldwide communications and information technology, as well as the development of international capital and service markets have led to a growing ‘transnationalisation’ of law, which no jurist can any longer afford to ignore. Europe – with its courts in Luxembourg and Strasbourg – acted as the main catalyst. National insularity or ignorance is no longer an option if Europe is to unite. The author has dedicated his academic life to the challenge of imparting this knowledge to others and bringing comparative law out of the university cloisters and into the reality of the courtroom in order to secure the existence of this subject in the future. He has remained true to his aims and convictions despite many critics and, at times, fierce opposition to his work. His courageous stance has impressed me deeply. It earns my unqualified admiration. It is thus with great pleasure and a sense of honour that I dedicate this foreword to him. As President of one of the highest courts in Germany I have obviously followed the author’s remarks on the state of comparative law in Germany with great interest. According to his accurate analysis, the case law of the Federal Supreme Court of Germany demonstrates a continued reluctance to avail itself of comparative law insights in the solution of legal problems. While comparative law analysis is applied where norms go back to international agreements or European directives, there is a clear deficit when it comes to the use of comparative law methods in the interpretation and closing of loopholes in purely national norms. Significant exceptions so far are the decisions of the Federal Court on the compensation for the infringement of personality rights (BGHZ 35, 363, 369) or for failed sterilisation and abortion ( i.e. the problems of ‘wrongful life’: BGHZ 86, 240, 250 f.) The chief cause of this marked reluctance, which the author explains in great detail in this book, is the lack of appealingly packaged foreign law material. Here the professional comparatist is required to immerse himself in the world of the foreign legal system and to convert foreign law into domestic categories. The author of this book achieved this brilliantly in his earlier work The German Law of Torts. A Comparative Treatise. Thus, this translation of German tort law into the English language contributed decisively to the fact that the decision of the English High Court in the case of Greatorex v Greatorex, which the author explores at length in his fourth chapter, was able to rely on, and did rely on, German decisions. The English Court here drew on foreign ideas as a medium for the continued development of national law. The author rightly wishes the same for German practitioners. He therefore advocates comparative law as a fifth interpretive method for which the German comparatist Konrad Zweigert has already pleaded in the past. The author uses the example of South Africa to demonstrate what a strong influence translated German statutes and case law can also have – and have had – on the development of the law of that country. The author attributes to German legislators a more progressive attitude towards comparative law. The completion of the reform of the law of obligations on 1 January 2002 bore the characteristic traits of a comparative approach. For, in the implementation of European directives, German legislators have allowed themselves to be guided by international law and important European codifications. The reform of civil procedure, which came into effect at the same time, also set itself the aim of adjusting Germany’s legal system to the standards of the country’s European neighbours and to take into account comparative law insights. The author ascribes a particular role for comparative law in European law to the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg and the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. The ECHR, which ascribes considerable importance to comparative law in the interpretation of European laws, has thereby in fact become the “stronghold of practical comparative law.” In order to drive this development forward, this book also makes a passionate appeal to legal practitioners of all countries to consult foreign law when national law exhibits gaps or appears unclear, contradictory, or unsatisfactory. Jurisprudence should meet the challenge set by the author to make the necessary material available in appropriate forms. Only such fruitful collaboration between theory and practice can pave the way towards a world in which language barriers are surmounted and the best legal solutions can be employed across national borders. This work also describes the personal legacy of the author for present and succeeding generations of comparatists. He bequeaths them his method of comparative law, which has proved itself not only in the area of private law, but can also function in public law, as the author demonstrates in one of his chapters. Though the area of public law is, admittedly, much more complicated because the ideological and political context projects itself more strongly on this part of the legal system than on private law, even here one can talk of rapid progress, partly forced by European integration. The author reviews the golden era of comparative law in the late 1960s, analyses its decline, and shows that his concrete, pragmatic and utilitarian approach will make comparative law useful for a politically and economically different world and also enable the subject to survive in the future. For comparative law raises awareness that the legal institutions and methods of domestic law do not provide the only possible solutions to social problems. It is an ‘antidote against blind dogmatism’ and liberates one from thinking in ivory towers. Comparison with foreign approaches safeguards intellectual flexibility and improves the understanding of one’s own and foreign legal systems. In this way, it not only advances the adaptation of European legal systems on the way to legal harmonisation, but, at the same time, promotes international understanding and thereby serves the international community. “For only through comparison can one differentiate oneself and find out what one is, in order to be sure what one should be” [Thomas Mann, Gesammelte Werke V, 2nd edition (1974), S. 142]. In this spirit I would like to recommend warmly this book to the reader and I wish him an insightful reading. Professor Dr. Günter Hirsch Präsident, Bundesgerichtshof