Sociolinguistic Engineering in A Globalised Economy Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies

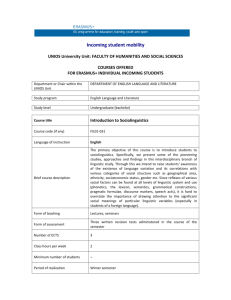

advertisement

E-ISSN 2281-4612 ISSN 2281-3993 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 3 No 4 July 2014 Sociolinguistic Engineering in A Globalised Economy James I. Udaa Olaoluwa Duro-Bello Department of English and Literary Studies, Federal University Lokoja – Nigeria Doi:10.5901/ajis.2014.v3n4p425 1. Introduction The fact that the world today is becoming a “global village” cannot be overemphasised. Geographical boundaries do not seem to be a hindrance to human interaction. The world seems deterritorialised and decompartmentalised. Can this phenomenal social intercourse be enhanced by linguistic factors? Which language plays what role in this global arena and what is the effect of this phenomenon on global economy? Answers to these questions and more are attempted in this paper. 2. Globalisation Globalisation, according to Friday-Otun (219), has become a process (or sets of processes) filtering into all domains of human experience - linguistic, social, cultural or economic. Thus, events in distant places simultaneously affect local affairs in different locations. Furthermore, Otun posits that “Language as a social dynamic is the nerve centre of all personal, interpersonal and transnational communication”. According to Jan Art Scolte (quoted by Otun, 220), “globalization” in political and academic sphere is a broad spectrum of separate political, economic, social and cultural phenomenon. Political scientists describe globalisation as the highest form of capitalism or exploitation in various forms from colonialism to neo-colonialism and to globalisation. It is a technique by the West to capture and manoeuvre developing nations through opening up “free markets” (liberal economy), information technology or “internet revolution” and the emergence of a unified community where the causes of social upheavals would disappear. The combination of linguistic engineering and marketing knowledge is required for what has been observed as “a broadening, deepening and speeding up of world-wide interconnectedness in all aspects of life” (Tom-Linson, 9 [quoted in Otun, 223]). This implies that linguistic developments at local levels in different parts of the world has global consequences, and the blurring or “annihilation” of boundaries between issues of domestic and global linguistic knowledge. This knowledge or linguistic association across the globe benefits from the spread of accelerated social activity through high-speed mobility of human and material resources across the world. 3. Sociolinguistic Engineering The most obvious definition of sociolinguistics is that it is the study of language in the society (Llamas, 150; Hudson, 1; Wardhaugh, 13). There is a social and contextual dimension to every naturally occurring use of language, and it is always these social factors that determine the choice and form of what is written or said or understood. Llaman and Stockwell (150) posit that a more complex definition of sociolinguistics is needed. To them therefore Sociolinguistics is the study of linguistic indicators of culture and power. This allows us to focus on language but at the same time emphasize the social force of language events in the world. This also allows us to use the tools of linguistics to see the influence of ethnicity, gender, ideology and social rank on language events. Above all, this definition allows sociolinguistics to be descriptive of pieces of language in the world, whilst encouraging us to recognise that we are all included in that world too. Thus, sociolinguists have a special responsibility to use their privileged knowledge to influence the direction of government language policies, educational practices and media representation around the globe. Capo (1) defines language engineering as that domain of applied linguistics concerned with the design and implementation of strategies (i.e. the conscious and deliberate steps) towards the rehabilitation and optimal utilisation of 425 E-ISSN 2281-4612 ISSN 2281-3993 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 3 No 4 July 2014 individual languages. In fact, it is a mechanism of language planning that recognises problems and proceeds to “engineer” solutions to such problems: codification, standardisation, modernisation, development, etc. Capo concludes that “language engineering is a continuing and dialectic process including orthography design, corpus planning, materials development, encouraging of language use at all levels to account for and communicate the changing experience of the speakers as well as all aspects of human legacy called knowledge. Akindele and Adegbite (74) also describe language planning as “a set of deliberate activities systematically designed to select from, organise and develop the language resources of a community in order to enhance the utilisation of such resources for development”. They further state that the goal of language planning is national development perceived in terms of political, socio-economic, educational, scientific, technological, literacy as well as language development. This idea is however limited to particular nations, making it difficult to apply to the international community. Since the world is rapidly changing, the languages of the world have to change functionally and structurally to reflect these changes which are political, social, economic, educational and technological. In Nigeria, for instance, upon the attainment of independence, agitations based on nationalistic ideas tend to result in the promotion, utilisation and development of indigenous languages which had hitherto been neglected officially. The break away from regional government to the creation of states and local governments made the administration become more and more decentralised. Thus, more and more languages have become recognised and are assigned functions to perform at different levels of government. There is no certainty as to any global convention that made the English Language a world language. Internationalism, which came via imperial and colonial activities, and linguistic assimilation lend credence to this. Linguistic assimilation is the belief that everyone, regardless of origin, should learn the dominant language of the society. For example, French in France (and her colonies), English in the USA and Britain (and their colonies) and Russia in the former Soviet Union (Akindele and Adegbite, 76). Internationalism, on the other hand, is the adoption of a non-indigenous language of wider communication either as an official language or such purposes as education or trade. For example, English in Singapore, India, the Philipines, Papau New Guinea and Nigeria. Sociolinguistic engineering in a global context could be seen as the process of assigning given roles or functions to existing standard languages to forge social or socio-economic cohesion. Assigning roles to languages in the global setting is not only difficult but a very complex issue. Power, both political and economic, takes the centre stage. This is however without effects on the global economy. One state or a limited number of states would certainly benefit more than a vast majority of other states. 4. Effects of Sociolinguistic Engineering in A Globalised Economy As stated earlier, the English language exerts a great deal of dominance in world affairs. Today, the English language has attained the status and nomenclature of an international language. Who is to blame? Is this a curse or a blessing? Quirk et al (2) posit that English is the world’s most important language. They make this assertion on the basis of four criteria considered as “objective standards of relative importance” for any language to be accorded such status. First is the number of native speakers that language happens to have. Second is the extent to which the language is geographically dispersed (i.e. in how many continents and countries is it used or is knowledge of it necessary?). Third is the ‘vehicular load’ (i.e. to what extent is it a medium for science or literature or other highly accorded cultural manifestation –including ‘way of life’?) and fourth is the economic and political influence of those who speak it as ‘their own’ language. None of these, they say, is trivial but that not all would unambiguously identify English. The first criterion would make English very poor, second to Chinese with double the number of its speakers. The second makes English a front runner but invites consideration of Hebrew, Latin and Arabic as languages used in major world religions. By the third, (aside being the language of great literatures of the Orient and of analogous Shakespeare), English scores as being the primary medium for twentieth century science and technology. The fourth criterion invokes Japanese, Chinese, Russian and German as languages of powerful, productive and influential communities. But English is the language of the United States which has a larger ‘Gross National Product’ (both in total and in relation to the population) than any other country in the world. The combined GNP of the USA, Canada and Britain according to Quirk et al, is 50 per cent higher than that of the remaining OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries (i.e. Continental Europe plus Japan). This position has not radically changed today (see work cited for website). Quirk et al argue that what emerges strikingly about English is that by any of the criteria it is prominent, by some, it is pre-eminent, and by a combination of the four, it is superlatively outstanding. Thus, it has been rightly said – they 426 E-ISSN 2281-4612 ISSN 2281-3993 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 3 No 4 July 2014 assert – that the choice of an international language, or lingua franca, is never based on linguistic or aesthetic criteria but always on political, economic and demographic ones (Quirk et al, 3). English is one of the two ‘working’ languages of the United Nations and of the two, it is by far the more frequently used both in debate and in general conduct of UN business. With the above status ascribed the English language notwithstanding, it has excluded a great number of the world population from global affairs. In Nigeria, for instance, a good majority of the population is excluded from national as well as international affairs. Oyelaran asserts that, “language is being used by the minority of commissioned agents to exclude the vast majority of Nigerians from participating in the affairs of the nation and therefore, from liberating themselves.” The 1979 constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, unabrogated, does not recognise the right of the individual Nigerian to receive information in a language of his choice other than the English language except when he is alleged to be a criminal. Oyelaran says: …until such an occasion arises, he is proscribed from expressing his own opinion about the laws or the process of making the laws under which he is governed, or the one under which he is being arrested unless he practises the English language. Even when arrested, he may just be informed in a language other than English about the nature of his offence and not at all about the law which authorises his arrest (12). The dire consequences of this are unimaginable. There are bound to be miscarriages of justice and entrenchment of political powers in the hands of the few who manage to gain control of the language. For instance, a satirical comedy on the NTA (Nigeria Television Authority) in the mid-1980s “Nchokwu” portrayed such miscarriage of justice causing many serious economic losses. Nchokwu worked as an interpreter for the Whiteman in the colonial era, and made very costly errors in his translations. Nigeria is only a microcosm of what is obtained worldwide. Linguistic pluralism is a global phenomenon. The recognition of more than one language (or code) is not without attendant effects. According to Levine (2001), reaching Chinese market is no longer an adventurous dream for U.S. firms as China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) integrates her into the global economy. Naming brands and having brand names translated into culturally heterogeneous and linguistically diverse consumers drive the global marketplace. In China, naming and translating a brand is more than assigning a symbol with pleasant sound, or giving the product a unique identity distinguishable from others. A brand name as a sociolinguistic symbol carries cultural meanings and sets boundaries on relationship building. For example, the sound “P&G” can have vulgar meanings in Chinese (expulsion of intestinal gas), but in the U.S. market it stands for Procter and Gamble Company. It was a problem when this multinational company entered China. Again, despite the dominance of English in the United States, it has always been a complex multilingual history. John Baugh (1) explains that in a global economy, the need to nurture, cultivate and manage multilingual resources within the United States is more pronounced than ever. Immigrants continually experience the ever-changing linguistic tides, yet yearn to share the American dream – a dream that exceeds their English fluency. Given the global economy, some of this linguistic management is being addressed by market forces, as advertisers and broadcasters strive to appeal to the ever growing number of non-English speakers who are U.S. residents; and citizens are increasingly important consumers of goods and services. Even politicians have been keen on learning new languages to demonstrate their empathy for non-English voters- votes that would significantly affect global policy. Some employers, multinational corporations and diplomats now recognise the value of linguistic diversity, placing great value upon the prospects of hiring bilingual or trilingual workers. Baugh cites one instance of the devastating effect of linguistic mismanagement. He says emergency relief workers (fire fighters, ambulance drivers, and hospital attendants) bemoan the fact that many human tragedies across the U.S. could be averted or diminished if it were not for communication gaps between those in need of emergency services (who do not frequently speak English) and first responders who lack ready access to vital linguistic translation. This is also applicable to many other parts of the world, including Nigeria. This too has dire consequences for the global economy. 5. Conclusion Issues of sociolinguistic engineering in a globalised economy are complex and varying. Language planning and choice in global context is difficult giving the great multilingual diversity around the world. English seems to occupy the centre stage of global linguistic affairs. This is not without attendant effects. Communities that use the English language must ensure the effective grasp of it in teaching to enhance genuine social and socio-economic cooperation the world over. It seems today that acquisition of English and one or two other languages avails better chances in multinational corporations. Multinational corporations, diplomats, military leaders and entrepreneurs who serve clients from diverse 427 E-ISSN 2281-4612 ISSN 2281-3993 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 3 No 4 July 2014 backgrounds exemplify the vast array of social circumstances where effective language planning and linguistics are vital assets. It is likely this state of affairs that a BBC documentary, Middle East Business Report, displays the use of Arabic on the BBC Network for advertisement in the Middle East. Consequently, the report shows that multinational companies would have to advertise and provide other pieces of information on the internet in Arabic to maintain being patronised. References Akindele, Femi and Wale Adegbite.The Sociology and Politics of English in Nigeria. Ile-Ife, Nigeria: ObafemiAwolowo University Press Limited, 1999. Baugh, John. Managing Language in a Multi-Cultural Nation Available: www.pbs.org/speak/speech Friday-Otun, J. O. “Globalisation and the Future of Nigerian Languages”. Sociolinguistics in the Nigerian Context.(Vol. 1) Ed. Dele Adeyanju. Ile-Ife, Nigeria: ObafemiAwolowo University Press Limited, 2007. Hudson, R. A. Sociolinguistics. (2nd Edition): Cambridge University Press, 1990 Li, Fengru et al (2003). Brand Naming in China: Sociolinguistic Implications [Comments]. Online Internet 2003. Available: http//www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi Llamas, Carmen and Peter Stockwell. “Sociolinguistics”. An Introduction to Applied Linguistics.Ed. Norbert Schmitt. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Oyelaran, O. O. “Language, Marginalization and National Development in Nigeria”. Multilingualism, Minority Languages and Language Policy in Nigeria. Ed. E.N. Emenanjo. Bendel: Central Books Limited, 1989. Quirk, Randolf et al. A Grammar of Contemporary English.London: Longman, 1972. Wardhaugh, R. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics.(5th Edition). Singapore: Blackwell, 2006. www.data.worldbank.org/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD 428