Document 11989017

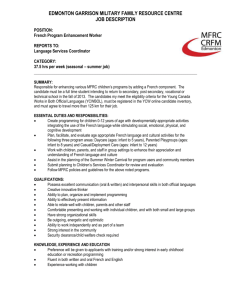

advertisement