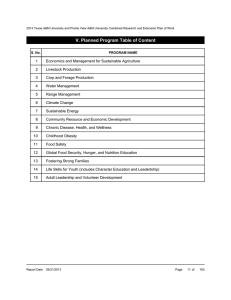

Full Tummies, Full Lives

advertisement