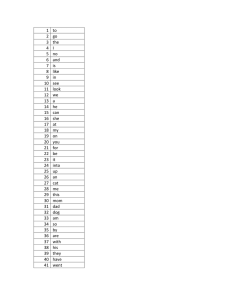

Studies in

advertisement