Document 11987442

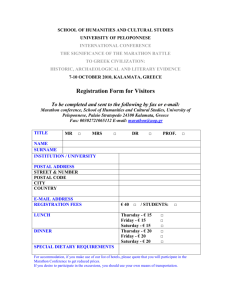

advertisement