Scott Aaron Palmer for the degree of Master of Arts...

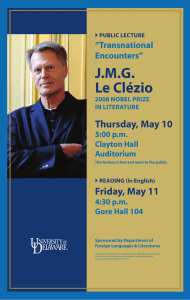

advertisement