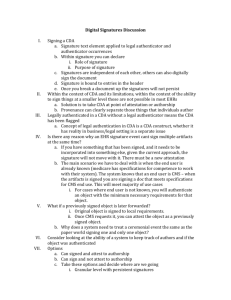

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Mary Ann

advertisement