Pergamon

advertisement

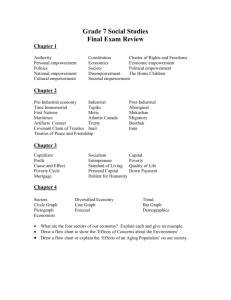

Teaching & Teacher Education, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 161-178, 1996 Copyright © 1996 Elsevier Science Ltd Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved 0742q)51X/96 $15.00 + 0.00 Pergamon 0742-051X(95)00030-5 THE DEVELOPMENT OF EMPOWERMENT EIGHT ELEMENTARY IN READING TEACHERS INSTRUCTION IN MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD University of South Florida, Tampa, U.S.A. K A R E N F. T H O M A S Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, U.S.A. Abstract--This paper describes a qualitative study of eight teachers identified as empowered or having become more empowered. The study focuses upon influences on and the developmental process of teacher empowerment. Findings demonstrated that gaining empowerment is a spiraling process in which teachers reach a point at which there is the realization that change is needed, then seek knowledge through professional training programs and experiences, and apply this new knowledge in making instructional changes in the classroom. Success in making changes leads to increased levels of confidence, and often, these changes lead to leadership roles which further enhance teacher confidence. Maeroff (1988) identified teacher empowerment as synonymous with professionalization and an essential component in the improvement of teaching and learning. Further, Ayers (1992) suggests that teacher empowerment is necessary in successful school restructuring and school reform efforts. He states: Empowerment is the heart and soul of teaching and it cannot be done well by the weak or the faint. There is no way for passive teachers to produce active students, for dull teachers to inspire bright students, for careless teachers to nurture caring students. Should teachers be empowered?Only if we want powerful students to emerge from our schools. (Ayers, 1992, p. 26) Similarly, Fagan (1989) explains that teachers must be empowered in order to empower, rather than disempower children. He views dependency as an opposite of empowerment and found that because too many teachers are dependent upon curriculum materials in teaching reading, children are disempowered as readers and writers (Fagan, 1989). If teacher empowerment leads to empowerment in literacy for children, it is important that educators thoroughly examine the processes involved in the development of teacher empowerment. Teacher empowerment has been defined as confidence in personal knowledge and in the ability to make decisions and take actions based on personal knowledge (BarksdaleLadd, 1994; Thomas, Barksdale-Ladd, & Jones, 1991). According to Lichtenstein, McLaughlin, and Knudsen (1992), "the 'knowledge' that empowers teachers is not the stuff of the weekend workshop or the after-school inservice session" (p. 41). Knowledge that empowers teachers and allows them to engage in their careers "with confidence, enthusiasm, and authority is a knowledge of the teaching profession, in the broadest sense" (Lichtenstein et al., 1992, p. 41). There are numerous recommendations in the literature for strategies intended to lead to the development of teacher empowerment. Unfortunately, few of these recommendations 161 162 MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD and KAREN F. THOMAS provide suggestions for teachers on how they might become empowered. For instance, Lichtenstein et al. (1992) advocate establishment of higher standards for beginning teachers as one approach to the development of teacher empowerment. Clearly, this suggestion is of little help to practicing teachers who wish to become empowered. Maeroff (1988) delineates a variety of strategies to encourage the development of empowerment. These strategies involve boosting teacher status, making teachers more knowledgeable, and allowing teachers access to power by providing time and opportunities for collegiality. Likewise, Prawat (1991) reports that collaborative relationships between teacher educators and public school teachers can lead to the development of empowerment. Kretovics, Farber, and Armaline (1991) suggest that teachers, parents, community members, and administrators should collaborate to reform schools, and through such collaborative work, teachers will become empowered. In a similar vein, Midgley and Wood (1993) found that when teachers collaborated in a site-based management plan to make changes in school culture, the teachers became empowered as a result. However, the recommendations of these authors focus upon the administrators and teacher educators who might make such collaboration possible; thus this information is not very helpful to teachers. Lightfoot (1986) recommends structuring schools to give teachers primary authority and responsibility for school-wide decision making. The implication is that ownership in decision making is necessary in developing empowerment. Again, teachers typically have little control over the degree to which they will be given ownership in the decisionmaking processes of their schools, so it is unlikely that these suggestions are helpful to teachers. Kincheloe (1991) and Houser (1990) tie the development of empowerment to knowledge gained through personal inquiry and suggest that teachers can gain personal empowerment through engaging in action research. Traditionally, teachers do not enter the profession with an understanding, the attendant skills, and an inclination to conduct action research. Further, in order to pursue this path to empowerment, teachers who are so inclined are likely to feel that they must seek training from experts. Situations which force teachers to seek knowledge from experts may to be disempowering situations, at least initially. Houston and Clift (1990) propose that empowerment and freedom are closely related to reflection, stating, "To reflect, an individual must not only be free to think, but also feel empowered to think" (p. 213). They state that legislative and administrative mandates limit teacher empowerment and reflection, implying that until teachers are given freedom to make decisions based solely upon professional judgment, it is unlikely that teachers will become empowered or reflective. Gitlin and Bullough (1989) examined empowerment in teacher evaluation, suggesting that horizontal, rather than hierarchal strategies for evaluation are needed to foster collegial relationships. In turn, these relationships are expected to lead to developing empowerment. Again, the recommendations of Houston and Clift (1990) and Gitlin and Bullough (1989) involve matters which are not controlled by teachers, therefore, these recommendations do not necessarily provide assistance to teachers. This body of literature leaves many questions unanswered. What if supportive contexts were established in schools where teachers had opportunities for ownership, collegiality and collaboration, responsibility for school-wide decision making, the ability to conduct action research, and horizontal evaluation methods? Would all the teachers become empowered? If not, who would? Who wouldn't? What factors would influence levels of development in the area of empowerment for different individuals? It is also important to point out that, in developing a wealth of recommended strategies and contexts to support the development of teacher empowerment, researchers have ignored an essential characteristic of empowerment. Empowerment is a characteristic which individual teachers must want; it cannot be given. In order to become empowered, teachers must first want to gain a power in the classroom which is embodied in confidence in the ability to make the most effective decisions for Empowerment in Reading their students' education and carry out the implementation of these decisions (Ayers, 1992; Barksdale-Ladd, 1994). To understand fully the process in which teachers develop empowerment, it is important that we look to those teachers considered to be empowered. It may be that empowered teachers can inform researchers, policy makers, administrators, and teachers themselves in more meaningful ways than can researchers who manipulate contexts for the purpose of supporting the development of empowerment. To address this issue, our study was designed to investigate the developing characteristics of attaining empowerment in elementary teachers. Because literacy instruction is a primary goal of elementary teaching, our study was directed at reading instruction. Our guiding inquiry, what does it mean to become empowered in teaching reading?, addressed the following specific questions: (a) How do empowered teachers become empowered?; (b) What do empowered teachers believe about reading and reading instruction?; and (c) How do empowered teachers teach reading? Design Participants A comparative design using empowered and unempowered teachers was rejected due to the implications and ethical considerations inherent in identification of unempowered teachers. Thus, we elected to identify more empowered teachers through a process based upon Chapter 1 teachers' (i.e., reading specialists who work with children in need of reading skills) nominations of classroom teachers. Because Chapter 1 teachers in a nearby school district were involved in a "push-in" rather than a "pull-out" reading program (i.e., Chapter 1 teachers work "in" the classroom with children in need of reading skills rather than pulling them "out") and worked daily in the classrooms with the teachers, we reasoned that they had the greatest awareness of teachers empowered, or becoming more empowered in the delivery of reading instruction. We expected that their daily interactions with the teachers and their observations of instruction and instructional changes over time would provide a solid foun- 163 dation for identification of the development of empowerment. We drafted a letter explaining the study and providing the definition of empowerment as "confidence in personal knowledge and the ability to make decisions and take actions based upon that knowledge." We sent this letter and the accompanying nomination form to all Chapter 1 reading teachers, a total of 16, in a rural school districts located in an eastern state. We asked them to nominate classroom teachers who matched the definition of empowerment, particularly in terms of reading instruction. Our letter specified that we would like nominations of teachers who were considered to "be empowered," as well as teachers who had "gained or grown in the area of empowerment." Each teacher was supplied with five nomination forms, however none returned more than one form, and no teacher was nominated more than one time. The teachers, representing 26 schools, nominated a total of eight teachers from eight different schools. Their nominations provided a one page description of ways in which nominees /fiatched the definition. If teachers felt that no teachers in their schools matched the definition of empowerment, they were asked to write "none" and return the form. They were not able to nominate themselves or other Chapter 1 teachers. Five teachers did return the form marked "none." Three of the teachers did not return a nomination form. We examined the information contained in the nomination forms as a method of considering whether or not the eight nominated teachers were "empowered or becoming more empowered in the delivery of reading instruction." In each case, the Chapter 1 teachers described teachers who had made instructional changes in the delivery of reading instruction. The nomination forms identified eight teachers who had gained new knowledge and applied their newly gained knowledge to changing their methods of reading instruction. However, the degree to which the teachers felt confident in their new knowledge was unclear from the nomination forms. All eight teachers identified as empowered agreed to participate in this study and we provided each a code name for each teacher to protect participant confidentiality. 164 MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD and KAREN F. THOMAS Procedure In order to triangulate our data sources, we conducted interviews, engaged in participant observation in each teachers' classroom, and kept reflective journals. We used the nomination forms completed by the Chapter 1 teachers as a supplemental data source. Our informal, semi-structured interviews lasting from 1 to 2 hours in length served as the primary data source. T h e interview formats, based on the research questions, focused on: (a) how teachers viewed themselves as teachers and as individuals; (b) descriptions of the process of their development as teachers and as empowered teachers; (c) descriptions of teacher beliefs about readers, reading, and the reading process; and (d) approaches to reading instruction and relationships between reading instruction and empowerment. The interview format is included in the Appendix. Probe questions allowed for complete explanations and rich descriptions. We then observed each teacher conducting reading and language arts instruction on two separate days after the interviews. During the observations, we recorded field notes on instructional practices and descriptions of activities in which the children engaged. In a pilot study, we found that empowerment did not appear to be a quality directly observable through a few short hours of participant observation; thus, we did not make empowerment a primary focus of the observation design. Rather, we observed for the purposes of: (a) getting a sense of how each teacher worked with children and (b) examining the relationship between how teachers described conducting reading instruction and their actual classroom practices. We conducted brief postobservation interviews to give teachers the opportunity to discuss our observations and to ask specific questions about lessons observed. Interviewers recorded journal entries of teacher perceptions and the interview process following each interview and classroom observation. We also recorded our personal perceptions about the interviews and observations. Journal entries helped to formalize a process for identifying our own biases and recording them on a regular basis during the data collection phase of the study. Additionally, journal entries served to record events which were not necessarily evident in the audiotaped interviews or field notes. For example, one participant cried during an interview and asked that the tape recorder be turned off during this time. The participant later stated that she was comfortable with our reporting her emotions and her reason for crying. The interviewer made a written record of what she said (while the tape recorder was off) and described the event in a journal entry written following the interview. Analysis We followed the phenomenological approach of Hycner (1985) to the analysis of the interviews. Written field notes, journal entries regarding perceptions of interviews and observations, and interview tra~,scripts comprised our data for analysis. After the tapes were transcribed, we began the analysis process by listening to each of the audiotaped interviews several times while reading the transcripts to understand the contexts in which teachers provided information. After reviewing transcripts in this holistic manner, we segmented idea units into units of general meaning. Units of general meaning were clustered around common themes or natural groupings, and we calculated intercoder reliability on the clustering of themes. Intercoder reliability on placement of ideas units within themes came out at .91 on a sampling of 1000 idea units (Yin, 1987). We compiled a detailed and extensive summary of the information gathered for each theme, then drafted the research report based upon both the'summaries for each individual and the categories identified during the analysis. As recommended by Hycner (1985), as a further method of triangulation we shared this draft with the teachers to assure that no misrepresentations were present. Teachers read the draft to examine (a) the accuracy of the information and (b) the logic of the interpretation (Whitford, 1981). Six of the teachers responded to the summary, however they identified no inaccuracies or illogical interpretations. Limitations The eight teachers in this study were caucasian and taught in a rural school district (see Table 1 for teacher details). The degree to which these results may be general- Empowerment in Reading 165 Table 1 Information on Participating Teachers Code n a m e Years teaching experience Current grade level Degree Gender Karen Nancy Katie Dottie Marilyn Anne Jean Joe 9 5 8 17 23 14 19 11 2 2 4 5 K 1 2 4 M.A. M.A. B.A. M.Ed. M.A. M.A. M.Ed. M.A. F F F F F F F M ized to differing populations in other settings m a y be limited. Additionally, in previous studies of empowerment, researchers have manipulated teaching situations or environments in different ways in order to provide settings which would encourage the development of empowerment. There were no such manipulations in this study, thus the degree to which these results are c o m p a r a b l e to those of manipulated e m p o w e r m e n t studies is limited. Results The following eight c o m m o n topics followed from our interview questions and form the basis for our data analysis: (a) teacher perceptions a b o u t empowerment; (b) teacher approaches to reading instruction; (c) teacher beliefs about reading and children; (d) childhood influences on the development of empowerment; (e) educational and teaching experience influences on the development of empowerment; (f) influences of other professionals upon the development of empowerment; (g) influences of inservice training and other professional workshops and experiences upon the development of empowerment; and (h) the influence of critical times in teaching upon the development of empowerment. We discuss each theme separately, using numerous and corroborative quotes from the participants to provide rich description. Wherever possible, we have preserved the actual language used in interviews in order to provide an accurate sense of the data and to allow the voices of the teachers. Perceptions About Empowerment Clearly, all teachers were genuinely pleased by their nominations and the accompanying reasoning provided by their colleagues. The teachers indicated that they "were honored" to be included in the study and impressed that others noticed their work and viewed them as empowered, or becoming more empowered. Anne's response was representative. She said, "Gosh, I didn't even know .that anyone paid that much attention to what I do, I mean, nobody ever tells you. It makes me feel real good...and it feels good that someone from the university thinks they can learn something from me, too." All teachers shared similar perceptions of themselves as "empowered teachers." That is, none of the eight teachers thought that they "were empowered." Rather, they indicated that they viewed themselves as engaging in the process of becoming empowered. They suggested that they were more empowered than they used to be, but they wanted to become more empowered than they currently were. Nancy expressed this when she said: I'm glad that I got nominated, but I'm not really sure that you want to interview me because I'm not sure whether I'm empowered or not. I do a lot of things really differently from how I used to, and I think that I'm getting empowered, quite a bit in fact, but I don't think I'm empowered yet. I want to be more empowered than I am, and I think I will be someday. Approaches to Reading Instruction A m o n g these eight empowered teachers, three , approaches to reading instruction prevailed: (a) Karen and Marilyn used a whole 166 MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD and KAREN F. THOMAS language approach; (b) Nancy, Anne, Jean, and Joe used what we term an eclectic approach; and (c) Katie and Dottie used C I R C (Cooperative Integrated Reading and Composition Program). For a description of CIRC, see the description of cooperative learning approaches to reading instruction by Slavin (1987). In the following sections, we describe each approach. Whole language. Karen and Marilyn rejected commercially prepared materials entirely and centered classroom instruction on literacy activities designed to match children's interests and needs. Karen, a second-grade teacher, discussed how she changed her approach to reading instruction and made it clear that her current primary focus centered on the needs of the her students. She said: For too many years, | followed those [teacher's] guides and worried and worried about the children because they didn't enjoy reading and many of them did so poorly and I couldn't help them....It was really frustrating....Now, I try to constantly pay attention to what they need at a given time. When I can see, like through their writing, that knowing a particular skill would help them and make things easier for them, that's when I introduce the skill. This never happened the way I used to teach. Karen addressed her children's needs through individual and cooperative readings of authentic literature, children's journal writing and the writing process, applications of art and music to literacy instruction, and integration of mathematics, science, and social studies within literacy instruction. Marilyn, a kindergarten teacher, had great difficulty answering questions about "reading" and "reading instruction," since she felt she didn't teach reading. She said: Well, it isn't like I stand up in front of them and teach them how to read. I read stories to them and we talk about them, and they write their news each week and we read and write that, and they write their own stories and books and we read those, but I wouldn't say that I teach reading....I just provide a lot of interesting opportunities to be involved in reading and writing and the children make their own choices about the activities they want to take part in. Marilyn's description closely matched our observations. Children engaged daily in a brief teacher-guided activity including discussions of the date, weather, and the weekly news dictated and read by the children. Then, the children chose from a variety of activities, moving freely from activity to activity. Children selected from a daily array of reading, listening, mathematics, manipulative, and writing activities. At the end of the half-day kindergarten sessions, a second teacher-guided activity engaged all children in acting out stories written by children using puppets and other props. Eclectic. Nancy, Anne, Jean, and Joe took an eclectic approach to reading instruction. The term "eclectic," refers to instruction in which teachers drew from a variety of sources and methods in designing and delivering reading instruction. All four used basal reading program materials to some extent, but they engaged in careful decision-making processes regarding which basal materials they would use and how they used them. All used some activities which could be considered reflective of holistic approaches to literacy instruction, Joe was very systematic and methodical in his approach, and considered himself to be a whole language teacher. Before the start of the school year, Joe identified the skills in the reading, language arts, spelling, mathematics, social studies, and science teacher's guides which he considered "essential for fourthgraders to learn." He then designed a series of month-long themes, determining how he would teach all of the identified essential skills across the year using his theme-guided plan. For example, one of the themes, "research," involved Joe identifying skills from each content area which he felt could be related to research and designing an instructional plan to teach all of the skills. We hesitated to consider Joe's instruction as a whole language approach given the following: (a) he had a strong focus on teaching individual skills in an isolated manner, and (b) he segmented each day into separate blocks of time for reading, spelling, handwriting, language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies. On the other hand, Joe designed m a n y creative, holistic, and integrated activities which were not skills focused. For example, Joe involved his fourth-graders in a book writing and publishing project in which they interviewed first-graders to discover Empowerment in Reading t h e i r interests, t h e n r e s e a r c h e d these a r e a s o f i n t e r e s t to w r i t e b o o k s f o r the first-graders. N a n c y c a r e f u l l y selected b a s a l m a t e r i a l s a n d employed many whole language kinds of activities. S h e said: I'm coming closer and closer to whole language, but I know that I'm not quite there yet. Next year I think I'll be able to let go of the workbook entirely and not make them do any of those workbook pages at all .... but it's been hard to let go of them all together because I know that the tests are coming up and the kids will look bad if they can't pass the tests. Nancy combined the basal with a variety of h o l i s t i c strategies. She d e v e l o p e d u n i t s integrating content areas with reading, writing, a n d c h i l d r e n ' s l i t e r a t u r e f o c u s i n g u p o n child r e n ' s needs. These children have very limited knowledge....They've never been to a big city. Pittsburgh [the nearby city] might as well be San Francisco, or Paris, as far as they're concerned. So I try to focus on the things they know and build from there, like almost all of them know about mountains and woods and we start with reading about those things in the early units. W h e n we o b s e r v e d N a n c y , the l a n g u a g e arts time block was evenly divided between basalb a s e d a n d w r i t i n g - b a s e d activities. W h e n a s k e d a b o u t h e r a p p r o a c h to r e a d i n g i n s t r u c t i o n , A n n e said: I use the basal a lot, but I also use language experience a lot. At the beginning of the year, we do a group dictated story every day, and we read these stories together over and over. They love them! As we progress through the year, we do less dictated group stories and more individual dictated stories, and then we move further and further toward having them write their own stories. A n n e filled h e r c l a s s r o o m w i t h stories t h a t children had written and published. Additionally, A n n e u s e d s u s t a i n e d silent r e a d i n g e a c h day. A n n e also s e p a r a t e d the c h i l d r e n i n t o abilityb a s e d b a s a l r e a d i n g g r o u p s . She m e t w i t h e a c h r e a d i n g g r o u p f o r 30 m i n u t e s e a c h d a y , t a k i n g the children through the basal program. Anne d i d n o t use all the r e c o m m e n d e d b a s a l activities, b u t she u s e d all the stories a n d m a n y o f t h e skills c h a r t s a n d w o r k b o o k pages. She said: I feel guilty about that....My principal really pressures us to use the basal and give the basal tests, and have the children successful on the basal tests, 167 and I want my job. He checks our lesson plans and comes by a lot and I'm not going to buck him! I had the children in the whole group at first...but it wasn't working because the better kids were bored and frustrated and they caused trouble, the lower kids were frustrated on the other end....I had these two kids who kept crying every day in reading and...it was reaching the point where all I had to do was say that it was time to get the reading books out, and, well, they would start up crying right then...I just ended up splitting the kids up into three reading groups. I'm embarrassed by that because I read the magazines, like The Reading Teacher, and they say that you shouldn't group, but it was amazing that when I grouped them, the crying and the frustration stopped....I guess I'm really confused about this, more confused than I thought. A n n e was a f r a i d t h a t h e r u n c e r t a i n t y a b o u t u s i n g the b a s a l a n d ability g r o u p i n g d i d n o t " r e a l l y q u a l i f y [her] as e m p o w e r e d . " She b e c a m e so e m o t i o n a l d u r i n g this p a r t o f the i n t e r v i e w t h a t she s t a r t e d cry. A t this p o i n t , the i n t e r v i e w e r o f f e r e d h e r r e a s s u r a n c e o f the i n t e g r i t y o f h e r feelings. J e a n d e s c r i b e d h e r a p p r o a c h to r e a d i n g i n s t r u c t i o n as " i n t e r d i s c i p l i n a r y . " She said: My primary approach to teaching reading is the basal, but I am very careful with it, a lot more careful than I used to be. I decide what I will use and what I won't use, and there is a lot that I don't use. J e a n p o i n t e d o u t several t i m e s t h a t m o v i n g f r o m ability g r o u p s to w h o l e g r o u p i n s t r u c t i o n (a r e c o m m e n d a t i o n in a r e c e n t l y a d o p t e d b a s a l r e a d i n g p r o g r a m ) w a s a m a j o r c h a n g e for her, a n d it was n e c e s s a r y b o t h to b e c o m e v e r y selective in c h o o s i n g basal m a t e r i a l s a n d to " s u p p l e m e n t the b a s a l w i t h m e a n i n g f u l a c t i v i t i e s . " I n d e s c r i b i n g h o w she s u p p l e m e n t e d t h e basal, J e a n said: Oh, I do hundreds of things. 1 have lots of cooking and baking activities and we write recipes and stories, like we make gingerbread houses at Christmas and we write our own gingerbread stories, and we go on lots of field trips, some being just walks through the neighborhood, and some being more academic, like to a museum, and we do lots of arts and crafts that use both reading and writing and we do letter writing to different people and companies and we write our own stories, and we read lots of children's books. I read to them at least once every day...and I think they're all learning to really love reading and writing, and I get terribly excited about that. W h e n we o b s e r v e d J e a n , she c h o s e n o t to use the basal, e x p l a i n i n g 168 MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD and KAREN F. THOMAS I guess I felt like I had to prove to you that I really was empowered, and I didn't think that for you to see me doing the basal, that would show that I was empowered. I wanted you to see the good stuff. Jean's classroom appeared to be as m u c h a whole language classroom as did M a r i l y n ' s a n d K a r e n ' s classrooms. However, because she typically used the basal p r o g r a m each day, we identified Jean as eclectic in her approach. CIRC. Katie a n d Dottie used the C I R C cooperative learning a p p r o a c h for reading instruction. C I R C is a cooperative learning m e t h o d designed to be used with the basal reading program. Dottie taught in a departmentalized c u r r i c u l u m structure, a n d she was responsible for teaching reading a n d language arts to all fifth-graders in her school in 90m i n u t e blocks. She used the C I R C a p p r o a c h t h r o u g h o u t the day in her reading a n d language arts instruction. Dottie said: I love the CIRC program. I think it really keeps the kids motivated in reading. We follow it to the letter, so we learn all of the vocabulary and we do all of the skills. The children read the stories to each other in pairs, so every child reads every story in its entirety to another child, and this is much better than the old round robin reading because they get so much more practice....I also supplement. I have training in library science, and I love children's literature, so we also read stories which are not in the basal, and I can apply the CIRC to that, too. We do the Junior Great Books Series, so we get involved in a lot of reading besides the basal W h e n we observed Dottie, she was n o t using the basal, b u t instead was applying C I R C to an adolescent novel. Similarly, Katie centered reading i n s t r u c t i o n a r o u n d the basal using the C I R C reading program. Katie said: I got trained in the CIRC program last year, so this is my second year of using it, but I've been very pleased. The kids enjoy it much more than straight basal reading instruction, and they like being active and involved with others and 1 think they learn a lot more.... I make a lot of changes in materials, and in what 1 decide to do, based on the kids themselves. I try hard to really pay attention to them, to what they know and what they do, and what they need and I change a lot of things to match their needs. K a t i e ' s classroom reading i n s t r u c t i o n accurately m a t c h e d her description of how she c o n d u c t e d instruction. Summary. Teachers identified as eclectic a n d C I R C in their reading a p p r o a c h used b o t h basal a n d n o n b a s a l materials a n d activities, whereas the whole language teachers used no basal materials. However, we viewed whole language, eclectic, a n d C I R C teachers as similar in three f u n d a m e n t a l ways. First, they all indicated that they paid careful a t t e n t i o n to student needs a n d student responses to instruction a n d m a d e decisions a b o u t reading instruction based u p o n their perceptions of student needs. Second, all of the teachers were d y n a m i c in their approaches to reading instruction, indicating that they had m a d e m a n y changes in their approaches to reading i n s t r u c t i o n a n d c o n t i n u a l l y m a d e a d d i t i o n a l changes. Third, all of the teachers were very enthusiastic a b o u t reading instruction. Beliefs About Reading and Children All b u t one of the teachers responded similarly to the questions regarding beliefs a b o u t children a n d reading. Their similar responses fell into the following subcategory beliefs: (a) m a k i n g reading i n s t r u c t i o n exciting a n d m e a n ingful for children will produce children who love reading a n d become readers; (b) p o o r readers generally have h a d less experience with literacy than good readers, a n d with appropriate experience they can become c o m p e t e n t readers; (c) teachers' attitudes a b o u t reading a n d e n t h u s i a s m toward reading instruction have a powerful effect on children's developm e n t as readers; a n d (d) all children should be read to regularly a n d should be provided with m a n y o p p o r t u n i t i e s to read good children's literature. Teacher responses d u r i n g the interviews closely m a t c h e d the i n s t r u c t i o n which we observed in the classroom. Jean's response, both descriptive a n d representative, was: Give me a child, and I'll teach 'em how to read. It doesn't matter if he is rich or poor, on the free lunch program or off, in special ed. or out, in Chapter 1 or out, it just doesn't matter, because they all can learn to read. They might not all turn out to be Einsteins, but they all can learn to read. I work as much at building good attitudes about reading as I work at anything....I have all kinds of exciting reading and writing experiences, and as long as I do that, I can't imagine a child not being able to learn to read or improve in reading. Empowerment in Reading Another interesting grouping within this theme involved self-reported changes in teacher beliefs over time. Five of the eight teachers indicated that when they began teaching, they thought that "some kids would learn to read well, and others wouldn't and it was just kind of like the result of intellect and it didn't have much to do with teaching," as Joe put it. After the teachers began to make significant changes in their instructional practices, they became aware of the tremendous impact that teaching has on the learner, and their beliefs about children and the teaching of reading began to change. Katie said: Before I started using CIRC, I just didn't know how powerful different types of instruction are, and when I saw the difference in the children, I started to see m y job as the teacher in a whole different light....It showed me for the first time that all of the kids really can be successful. Dottie's responses to these questions differed somewhat from the other teachers. While she stated that teachers must make reading interesting and exciting for children, and that teacher attitudes toward reading affect children's development, she did not think that all children could learn to read well. She said: No, I don't think so. ! wish I could believe that all children could become good readers, but I have had too m u c h experience to say that I think that's true. There are too m a n y factors that affect whether they will read or not which are out of the teacher's hands. The kids that we get here, most of them don't come from homes where the parents read. I've been to the homes, and there's not a magazine or a newspaper or a book anywhere in the house, but there's always the T.V. They come to expect to be entertained the way a T.V. program entertains, and reading is too much work, and besides, reading is just a school thing to them. It's something that you have to do in school, but nowhere else, and they don't ever get to see their parents read, and their brothers and sisters only read to do homework for school, and they tend to hang around with other kids like themselves, so there just isn't anything to get these kids going with reading....I'm not convinced that all kids can learn to read unless there is something away from the school that means something to them that encourages them to become good readers. When we observed Dottie, her differing beliefs about reading acquisition were not apparent in her instruction. She appeared to be quite inspired about teaching the novel selected for the children, and we witnessed numerous 169 instances of her modeling positive attitudes about reading. Childhood Influences In examining childhood influences on reading instruction and empowerment, we found similarities among these teachers. No teachers felt that aspects of their childhood had led toward the development of empowerment, but all of the teachers felt that childhood influences affected the way that they currently taught reading. For example, Karen attended a one-room school, and she felt that whole language was similar to classroom life in a one-room school. She loved the one-room school and had flourished as a reader in this environment, and she felt that she could set up a similar environment for her students through whole language. Nancy was a poor reader as a child, consequently she was "put in all of these programs to get help in reading." She felt that she had a special affinity for children who had difficulty learning to read, and that this affected her ability and desire to design reading instruction which would be meaningful for these children. Similarly, each teacher told of readingrelated childhood experiences associated with their current instructional practices. Influences of Educational and Teaching Experiences All but one of the teachers, Katie, had a master's level degree in education. Dottie, Marilyn, and Anne had taken between 15 and 45 credit hours of graduate level coursework beyond their master's degrees. All eight teachers stated that their undergraduate programs had little effect on how they conducted reading instruction at any time in their professional careers, and that similarly, their undergraduate programs had not had an effect on their development as empowered teachers. They were able to remember very little of what they had been taught about reading instruction in their undergraduate programs. For example, Joe said, "Well, they made us learn a lot of phonics and write lesson plans, but I don't really remember anything about it. I don't even know who taught it."" In discussing the effects of graduate level training in education, two teachers, Nancy and 170 MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD and KAREN F. THOMAS Marilyn, said that they had taken reading courses in which they had learned some methods and techniques which they had applied in their classroom teaching. However, neither teacher was able to specify a strategy currently used which they learned during graduate-level training. The remaining five teachers with graduate level degrees stated that they made no changes in reading instruction as a result of their graduate training. These five teachers remembered very little about reading instruction in their graduate studies although each had taken at least one graduate-level reading course. These teachers also indicated that graduate-level training had no impact on their development as empowered teachers. Influence of Other Professionals Responses to questions on meaningful colleagial relationship did not verify the importance of colleagial support in developing a sense of empowerment. Of the eight teachers, Dottie and Nancy noted supportive colleague relationships. The other six teachers did not feel that relationships with colleagues contributed to the development of empowerment. Dottie noted that one of her friends who taught at another school at the same grade level attended C I R C training with her and they talked on the phone frequently. However, teaching was not the major conversational topic for them. Dottie said that if she ever felt like she "was really having a problem, or was very frustrated with a child," she might call this friend to talk about it, but "since they didn't teach in the same school," she would "only call to vent her frustration." Nancy indicated that she talked frequently about instruction with the first-grade teacher and the Chapter 1 teacher in her school, because they provided support for one another. Nancy said, "because all three of us are interested in whole language and are working to implement as much whole language as we can, we talk after school sometimes about what we are doing and we share ideas." However, Nancy did not feel that this colleagial relationship influenced her development of empowerment. Anne indicated that her relationship with her spouse influenced her development of empow- erment while relationships with other teachers had not been important. She said: Really, it has been my husband, not them. He loves children, and he loves it that I am a teacher, and he always tells me that I am the teacher, and that I know those kids better than anyone else, and that I should do what is right for the kids. That support has a lot more effectthan the talking with other teachers. Influences of Professional Workshops and Other Professional Experiences We found involvement in programs and workshops c o m m o n to all eight teachers in the development of empowerment. This involvement led to three empowering aspects: confidence, changes in instructional practices, and leadership within their schools. The following programs were instrumental in the empowerment process: (a) C I R C training for Dottie and Katie; (b) TESA training for Anne; (c) the state Teachers' Academy for Jean and Joe; (d) a week-long Whole Language Workshop for Karen; (e) a Fulbright Exchange for Marilyn; and (f) a series of different inservices and workshops for Nancy. As a direct result of C I R C training, Dottie and Katie indicated they gained a great deal of confidence in their ability to do "new" things in the classroom successfully. After success with CIRC, they began to experiment with other new methods of instruction and applications of cooperative learning. For example, Dottle was applying C I R C to reading an adolescent novel. Additionally, Dottie and Katie had become "leaders" in their schools as a result of CIRC. They had"been given opportunities to share cooperative learning methods in their schools and other schools. The combined effects of their success in implementing new strategies for reading instruction and becoming school leaders led to high levels of confidence. Katie explained: I think that when I first started using CIRC, I started to becomeempoweredfor the first time because all of the sudden I found out that I could completely change how I taught and do it with success....I was changing, and it was very exciting, and then I got to go to some schools and talk to other teachers, train them about using CIRC, and that is when I really got more empowered.Not only was I able to change what I did in the classroom, but I was able to teach other teachers how they could change. Empowerment in Reading Anne's involvement in TESA was instrumental in the development of empowerment for her. In this program, teachers trained in effective teaching strategies observed other teachers and were observed regularly by teachers. The purpose of the observations was to assist and provide support for incorporating the effective teaching strategies. Through involvement in TESA, Anne learned for the first time that what she was doing was "normal" and that much of what she was doing was "quite good." As a result, her confidence in herself as a teacher increased and she felt that she could successfully implement innovations in the classroom. Anne said: It seems strange now, but before I did TESA, I was never sure, never sure about what I was doing....I got to see that they [other TESA teachers] did the same things I did and had the same problems, and sometimes they really liked things I did, and they were going to go back to their own classrooms and try them. It was really rewarding and empowering for me. Anne noted that other teachers in her school had gained respect for her saying, "That sort of empowers you, too, when other people have confidence in you." Jean and Joe were selected for the state Teachers' Academy, and their "stories" were quite similar. Both felt that being chosen for the Teachers' Academy had been an honor. They said that upon arriving for the week-long summer program, they were told that they were among the "best and the brightest" of the state's teachers. Like Anne, before their involvement in this program, Joe and Jean had never been sure that they were good teachers. Jean said: When I was picked for the Teachers' Academy, I thought that probably no one else in our county had applied, and that was the only reason 1 was chosen, but while 1 was there, I really got convinced that I was pretty good. Joe said: Before the Teachers' Academy, I think I was pretty m u c h a run of the mill, follow the book, follow the curriculum, do what the other teachers do kind of teacher, but after, when I came back to school the next year, I really felt different, like I could do whatever I wanted to do to help the kids, and that I could do it well....I think that the Teachers' Academy was the push that I needed to start becoming empowered. 171 Karen had been involved in a week-long whole language workshop which had given her the inspiration and confidence to implement whole language in her own classroom. She said: I saw this pamphlet lying in the teacher's lounge about a whole language workshop....I didn't really even know what whole language was, but...I went off to Boston by myself to this workshop and, Wow! W h a t an experience! It was like they were telling me that all of my instincts about teaching reading were right, and everything I had been taught and had been doing was not wrong, but not as good as it could be, and I listened like crazy and asked questions in meetings whenever I didn't understand, and stayed after the meetings to talk to the presenters, and I spent lots of money on materials and books, and I came home a n e w p e r s o n . I knew exactly what I wanted to do. When Karen announced in her school that she would not be following the basal and would be using whole language, several other teachers felt that they should learn about whole language and try some whole language activities in their classrooms. Karen became a leader in her school because she met regularly with other teachers, informing and assisting them in whole language. The empowering experience for Marilyn involved her teaching for a year in the Fulbright Exchange Program in England. She reported that this experience led to developing a high level of confidence in her own ability to design and implement appropriate instruction for young children. Since that time, she has found herself in leadership positions often. Marilyn said: The Fulbright is what did it for me. It was a wonderful experience, and it was one of those things where you just go off and figure it out as you go along. I was a lead teacher over there and I got to do a lot of things, and this had a big impact, and I came back here with a lot more confidence than I ever had before....It's really important to read the journals, because they keep you up to date, and it's great when you read something, and you think, "Gee, that's not new. I've been doing that for a long time." Probably my Fulbright, and my reading and keeping up with things and doing what I believe is best for the children, that got me started and keeps me moving in being empowered. Nancy was somewhat different from the other teachers in that she did not specify one particular program, workshop, or experience which had an impact on her developing empowerment. Nancy said: 172 MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD and KAREN F. THOMAS I think that the workshops have been the thing. I finished my Master's in reading last year, and I knew that...l had to change what I was doing in reading. Getting my Master's was great...but it didn't teach me how to change what I was doing and make it better....l started going to these workshops, mostly whole language workshops because 1 heard a lot about whole language in my Master's, but I never heard h o w you do it, and the workshops started making a difference. Like, I would pick up a few ideas in a workshop and I would ask questions about how to use them, and then 1 would come back to the classroom and try them....I think I feel a lot more comfortable in workshops [than classes]. They teach you something new to do to change your instruction, and they are willing to make it specific and a lot of them, they care whether you do it or not...care enough that they'll say "you can call," or they'll come back if there are questions....The more workshops I've gone to, and the more new things I've been able to do, the more empowered I've started to be. Nancy indicated that other teachers in her school knew that she had made a variety of changes in her instruction, and they had begun to come to her for help in solving problems and creating ideas. Although she assumed no "formal" leadership role, Nancy viewed herself as a leader in her school. In summary, all teachers participated in programs or workshops resulting in new knowledge and strategies for changing classroom instruction. These programs/workshops inspired confidence and the teachers found themselves successfully applying new knowledge and making changes. This success led to higher levels of confidence, which in turn led to more changes. As a result, all of the teachers became leaders or began to perceive themselves as leaders after their involvement in these professional learning experiences. The Influence of Critical Times in Teaching Another common empowering event for all eight teachers occurred when they reached points in their careers impelling them to change. Using Karen's words, we termed these points "critical" times in teaching. She said: It was that I had reached a point, a really important and critical point for me, where I really simply could not go on doing what I was doing. For year after year I had been dealing with discipline problems which I knew were the result of the fact that the instruction was so boring and meaningless for the children, but I just kept doing the same thing each year. 1 think I knew that if 1 didn't change what I was doing I couldn't stay in teaching in the long run....I needed some vehicle, something to show me h o w to make those changes. It was just critical that I change at that point. Similarly, Joe stated, "I was really frustrated....It was an odd time for me because it seemed that nothing was right in my life, but at the same time nothing was wrong. I needed to be able to change, to make things different." When these teachers reached their personal critical times, they sought professional learning experiences in the form of workshops and programs designed to assist teachers in making changes. They embraced new information. Jean discussed embracing new information received in her program and questioned the relationship between critical times in teaching and workshops/programs which empower. She said: You know, I have been teaching forever, it seems like, and I have been to hundreds, maybe a thousand workshops....They sure didn't make me empowered. But I think I was different. I had become uncomfortable....l can say that the Teachers' Academy empowered me, but l ' m still not sure that it was the Teachers' Academy because I was so different, that I probably should say it was the time I was going through as much as the academy that helped me start to change and start to get more empowered. Discussion In the study, we sought to examine what is involved in the process of becoming empowered in teaching reading. Specifically, we sought to inquire into the: (a) influences on the development of empowerment in the teaching of reading; (b) the beliefs about children, reading, and reading instruction held by empowered teachers; and (c) the approaches used by empowered teachers in the design and delivery of reading instruction. Most recommendations for increasing levels of teacher empowerment in the past have not contained suggestions to teachers who might wish to become more empowered. Our results indicate that gaining empowerment is a spiraling process. First, a teacher reaches a point at which there is the realization that change is needed. Then, this teacher seeks knowledge, through professional training programs and experiences. Next, the teacher applies this new knowledge and makes -instructional changes in Empowerment in Reading the classroom. Success in making these changes leads to increased levels of confidence. Often, these changes lead to leadership roles and responsibilities which enhance teacher confidence. The process spirals in that teachers continue to seek new knowledge and new classroom changes over time. Understanding this process may provide teachers who wish to become more empowered a framework for getting started. In our study, some of the teachers' experiences fell outside existing descriptions of supportive influences upon the development of empowerment reviewed at the outset of this study, and other experiences fit the descriptions. Maeroff (1988) suggested that boosting teacher status and making teachers more knowledgeable aid in the development of empowerment. Similarly, Harris-Sharpies, Kearns, and Miller (1989), Kretovics et al. (1991), and Midgley and Wood (1993), found that teachers began to feel empowered through programs which valued teachers and involved them in school leadership. Clearly, through the professional programs they selected to be involved in, these teachers gained knowledge allowing them to take risks and make instructional changes. Consequently, their status changed as they assumed leadership roles. Kincheloe (1991) and Houser (1990) advocate that empowerment is gained through personal inquiry and recommend that teachers engage in action research. Although not engaged in "formal" action research, we found that these teachers were informally engaged in developing personal knowledge through their personal inquiry. They successfully changed their classroom practices through personal inquiry thereby benefiting both themselves and their students. Successful change played an important role in their development of empowerment because their success led to confidence. These eight teachers did not corroborate the assertion from the work of Lightfoot (1986) that ownership in school-wide decision-making processes is necessary in the development of empowerment. The empowered teachers in this study never discussed decision making from a school-wide perspective, however, we found their decision making reflective of their students' needs and interests through the selection of appropriate instructional practices and 173 materials. So, taking ownership over decisionmaking processes in individual classrooms did appear to be related to the development of empowerment. Likewise, these teachers did not back up Houston and Clift's (1990) suggestions that empowerment calls for teachers being freed from administrative and legislative mandates to make decisions based upon professional and reflective judgment if they are to become empowered or reflective. These eight teachers were quite reflective in their decision-making processes about instruction even though they had not been freed from the constraints of legislative or administrative mandates. In fact, most demonstrated that they had reflected seriously upon legislative and administrative mandates. For example, Joe talked at length about the reflective process in which he had engaged. He explained: I am always, and I mean always, constantly, thinking about that, figuring out, exactly how far I could go in ignoring what is expected by the state and the county to make sure I meet the needs of the kids, while still making sure that I don't make anyone around here too mad at me. It's like walking a tightrope every day, but it has been worth it for the kids, and for me, too. Based on the responses of these teachers, we take the position that complete freedom from administrative and legislative mandates may not be necessary in the development of empowerment. A t the same time, we noted that freedom from such mandates would have allowed the teachers to reflect more upon the needs of their students, thereby spending less time pondering the degrees to which they could ignore or circumvent compliance with mandates. Maeroff (1988) and Winograd (1989) suggest that opportunities must be provided for teachers to establish supportive colleague relationships in order for empowerment to develop. Based on teacher responses regarding colleagial relationships, we found that collaborative relationships did not play a significant role in the development of empowerment for these teachers. Because these teachers participated in professional development programs with other teachers, we submit they did not develop empowerment in isolation. However, they did not cite supportive colleague relationships as 174 MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD and KAREN F. THOMAS empowering, despite an extensive line of questioning regarding such relationships. The lack of supportive collegial relationships could be a rural school phenomenon. The rural schools in which these teachers worked offered few opportunities for collaboration. Planning periods typically did not occur at times when other teachers had planning periods. For example, in Jean's school, there were four teachers. Jean taught second-grade and there was a first-second combination, third fourth combination, and a fifth-sixth combination classroom. Art, music, and P.E. teachers came to the school once a week, so Jean had three planning periods, but no other teachers had planning periods at the same time. In small schools where teachers do not have opportunities to meet and talk with one another, it may be particularly difficult to establish collaborative teaching relationships. Another teacher, Marilyn, taught in a Professional Development School which was currently engaged in a restructuring process in collaboration with the university. It might be expected that a teacher in a school involved in restructuring would have developed some collaborative and supportive relationships. As Marilyn described her school, this did not appear to be the case. Marilyn's critical time, when she began to become empowered as a result of a Fulbright Exchange program, was in the early 1980s. Marilyn indicated that she had been engaged in a process of becoming more and more empowered for over 10 years. According to Marilyn, she had moved far beyond her peers in terms of professional development. She did not feel that they were interested in what she had to offer, nor was she interested in what they had to offer. It is reasonable that teachers in situations like Jean's and Marilyn's might not have developed close and supportive colleague relationships. Thus, we do not take the position that supportive colleague relationships are necessary for empowerment to develop. Based on the results of this study, we question both the role and the significance of colleague relationships in developing empowerment and recommend further research in examining empowerment in a variety of educational settings. Our second inquiry examined empowered teachers' beliefs about children, reading, and reading instruction. All eight teachers believed that teachers' attitudes and enthusiasm toward reading had a powerful impact on children's development as readers, and that reading to children and providing opportunities for reading literature at school were imperatives in a sound reading program. All but one of these teachers believed that making reading instruction exciting and meaningful for children will motivate children to learn to love reading. Allington (1991) argued that teacher beliefs drive reading instruction. Based upon both interviews and observations, our findings suggest that development of empowerment paralleled the development of positive teacher beliefs about how children learn to read. Teachers appeared to go through a process in which they viewed all learning to take place outside the student and teacher working together. Rather, teachers viewed the materials and the accomplishment of some curriculum on the part of students as literacy instruction. Teachers covered the curriculum and students' abilities either helped them through or failed them. Teacher descriptions of their own change processes indicated that they moved from being teachers who were dependent, compliant, and teacher/materials centered, to becoming teachers who were more empowered and child centered. This process then meant making decisions based upon perceived students' needs and matching these needs with interactions among teacher instruction, methodology, and materials. Simultaneously, changes in beliefs and practices accompanied the move to child-centered instruction and empowerment. Our third area of inquiry focused upon teacher approaches to reading instruction. These empowered teachers used a variety of approaches in their design and delivery of reading instruction including whole language, eclectic, and cooperative learning approaches. The whole language teachers rejected the use of commercially prepared materials while the other six selectively used these materials in conducting reading instruction. Of the teachers who used the basal programs, none followed the recommendations in a technical, step-bystep manner. These teachers carefully made decisions about what materials to use and not use based upon the needs of the children. Empowerment in Reading According to Duffy (1991), when teachers are becoming empowered, they use conceptual selectivity by controlling instruction in selecting the materials to be used, organizing the curriculum, and designing the instruction. All eight teachers actively engaged in making decisions which led to literacy instruction enriched beyond technical basal-based instruction. Through the study, we concluded that empowerment could be most meaningfully understood when placed on a continuum. These teachers made it clear that empowerment is a process, not an outcome, as has been pointed out by Brown (1992) and Ayers (1992). We found that the use of the isolated terms "teacher empowerment" and "empowered teachers," inherently included an implication that empowerment is an outcome. In many ways, the perception of empowerment as an outcome is a way of perpetuating a system in which researchers and teacher educators are at the top, in the "cult of the expert" (Kincheloe, 1991, p. 20) and teachers are at the bottom. Much has been written about the need for teachers to become empowered, but these teachers had no way of knowing when or whether they have reached that goal. At any stage in this process they were likely to view themselves as becoming empowered--more empowered than they used to be, but not as empowered as they wanted to be. They concluded that they must not have yet reached the goal of becoming empowered, since they desired to be more empowered than they were. As a result of this perception, these teachers placed themselves in a subservient role to researchers and teacher educators. It is essential that teacher educators and researchers send teachers the message that empowerment is a process. Empowerment is not a characteristic of which persons can be devoid, in the same way that self-esteem is not a characteristic of which persons can be devoid. Rather, both empowerment and selfesteem are attributes that all people possess in some degree. Dependency or compliancy may be viewed at one end of the continuum and empowerment at the other, as suggested by Fagan (1989) and Barksdale-Ladd (1994). Further, we must emphasize a related point, that becoming more empowered does not mean losing the sense of uncertainty. Uncer- 175 tainty is clearly a fact of teaching. Fraatz (1987) discusses this concept as "professional uncertainty" in teaching. Duffy (1991) discusses it in terms of the ability of teachers who are becoming empowered to tolerate "ambiguity." The teachers in this study were disturbed when they discussed the fact that they were often uncertain about how they taught reading, and sure that they needed to make changes. Their perception was that, as teachers who had been identified as being empowered, they ought to have a lot more answers than they had. Anne most notably demonstrated this when she cried over her concerns about using basal materials and ability groups. Anne's perception was that, as university reading instructors conducting research, we would not view a person who used the basal and separated the class into ability groups as being empowered. She said, "I was almost afraid that you would decide that I wasn't empowered and not even finish the interview." Similarly, Jean was apologetic about her use of a basal program and would not use the basal to conduct reading instruction ix;' the usual manner when we observed her. Jean felt that using the basal in conducting reading instruction would not enhance our perceptions of her level of empowerment. In order to dispel perceptions that empowerment means the loss of uncertainty, it is important that researchers and teacher educators make clear that all educators (themselves included) live with uncertainty regarding their teaching. This uncertainty may be used as a tool to lead us continually toward seeking solutions and improving instruction. Two related perceptions held by the teachers in this study surfaced: (a) closely following basal programs is not the best practice in teaching reading and (b) empowered teachers are examples of those using the best of practices in teaching. Because they held these perceptions, the teachers who used basals were embarrassed and felt that they might not actually be empowered. It may be important for researchers to work at sending the message that a teacher's choice of materials to be utilized in the delivery of instruction is not necessarily a significant issue in empowerment. More crucial issues in empowerment should address changing instructional practices and developing increasing levels of conceptual selec- 176 MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD and KAREN F. THOMAS tivity in making decisions about instruction and materials. The results of this study lead to further questions about developing empowerment. First, what is it about the professional experiences in which these teachers engaged that led to the development of empowerment? Secondly, how important are these professional experiences in the development of empowerment? Involvement in professional experiences provided the impetus for these teachers, but these experiences were not the key to the development of empowerment. When sharing this study with a group of teachers, one responded to the results with great surprise. She said, Well, I've taken CIRC (Cooperative Integrated Reading and Composition), and TESA, and I've been to plenty of other workshops, and they sure didn't have that effect on me. I want to be empowered, and I've taken all of those programs, but I'm not empowered. Surely, there are many hundreds of other teachers who have been involved in these and similar programs but who did not find themselves progressing in the process of becoming empowered as a result. We maintain that the key involves teachers reaching a critical time in their professional careers at which they want and need to make changes in their approaches to teaching, and in finding success in making changes. Supporting teachers in reaching critical points and finding success in the change process may be important roles for teacher educators. How did these teachers reach their critical times, and can teacher educators play a role in encouraging teachers to reach a critical time? We discovered the descriptions of critical times in teaching during data analysis procedures; thus it was too late for an examination of this issue. Further research is needed. One teacher, Nancy, indicated that her Master's degree program in reading raised many questions for her, and that she graduated from the program knowing that she needed to change, but not knowing how to change. This was Nancy's critical time, and it led her to seek professional experiences to assist her in finding ways of actually making changes. It may be that teacher education programs can lead teachers to reach critical times. Also, some teachers may be much more likely to reach critical times than others. A burning question for teacher educators to grapple with is: Why is it that teacher education programs at both undergraduate and graduate levels appear to have virtually no influence upon the development of empowerment? Duffy (1991) finds that through the expectations set by reading researchers and educators, teachers are disempowered rather than empowered. When reading educators place themselves above teachers with expectations about what teachers need to know and what teachers need to do in courses and other interactions, they imply possession of valuable knowledge to be sparingly passed down to teachers. As we "pass this knowledge down" in our classes, we also send the message that it is important that we evaluate the degree to which teachers have learned and can use the knowledge we share. When we consider the development of empowerment, it is particularly important, as Duffy (1991) pointed out, to let teachers know that we dofi't know all the answers and that appropriate answers in teaching are largely dependent upon circumstances. If we are to play a role in the development of teacher empowerment, it is essential that researchers and teacher educators begin to move toward partnerships and collaboratives to learn with teachers rather than assume roles as superiors who pass knowledge down. References Allington, R. L. (1991). The legacy of "slow it down and make it more concrete." In J. Zutell & S. McCormack (Eds.), Learner Jactors/teacher factors." Issues in literacy research and instruction (pp. 19-30). Chicago, IL: National Reading Conference. Ayers, W. (1992). Work that is real: Why teachers should be empowered. In G. A. Hess, Jr. (Ed.), Empowering teachers and parents. School restructuring through the eyes of anthropologists (pp. 13 28). Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey. Barksdale-Ladd, M. A. (1994). Teacher empowerment and literacy instruction in three Professional Development Schools. The Journal of Teacher Education, 45(2), 104~I 1I. Brown, M. J. M. (1992). Rural science and mathematics education: Empowerment throught self-reflection and expanding curricular alternatives. In G. A. Hess, Jr. (Ed.), Empowering teachers and parents. School restructuring through the eyes of anthropologists (pp. 2946). Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey. Duffy, G. G. (1991). What counts in teacher education? Dilemmas in educating empowered teachers. In J. Empowerment in Reading 177 National Reading Conference. Zutell & S. McCormack (Eds.), Learner factors/teacher Whitford, B. L. (1981). Curriculum change and the effects of factors: Issues in literacy research and instruction (pp. organizational context: A case study. Unpublished 1-18). Chicago, IL: National Reading Conference. doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina, Fagan, W. T. (1989). Empowered students: Empowered Chapel Hill. teachers. The Reading Teacher, 42, 572-578. Fraatz, M. J. B. (1987). The politics of reading." Power, Winograd, P. (1989). Improving reading instruction: Beyond the carrot and the stick. Theory into Practice, opportunity, and prospects for change in America's 28, 240-247. public schools. New York: Teachers College Press. Yin, R.K. (1987). Case study research: Design and methods. Gitlin, A., & Bullough, R. (1989). Teacher evaluation Newbury Park, CA: Sage. and empowerment: Challenging the taken-for-granted view teaching. In L. Weis, P. G. Altbach, G. P. Kelly, H. G. Petrie, & S. Slaughter (Eds.), Crisis in teaching. Perspectives on current reform (p. 183APPENDIX 203). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Empowerment in Reading Interview Format Harris-Sharpies, S. H., Kearns, D. G., & Miller, M. S. (1989). A young authors program: One model for 1. Response to Being Interviewed Regarding teacher and student empowerment. The Reading Empowerment Teacher, 42, 580-583. Houser, N. O. (1990). Teacher-researcher: The synthesis of • Display copy of empowerment definiroles for teacher empowerment. Action in Teacher tion, read nomination form which was Education, 12(2), 55-60. submitted for the teacher being interHouston, W. R., & Clift, R. T. (1990). The potential for viewed, and ask about responses to the research contributions to reflective practice. In R. T. nomination. Clift, W. R. Houston, & M. C. Pugach (Eds.), Encouraging reflective practice in education. An analysis of issues 2. Approaches to Reading Instruction and programs (pp. 208 222). New York: Teachers • Ask for description of teacher's College Press. approach to reading instructiow in the Hycner, R. H. (1985). Some guidelines for the phenomenoclassroom. logical analysis of interview data. Human Studies, 8, • Ask about use of materials for reading 279-303. Kincheloe, J. L. (1991) Teachers as researchers: Qualitative instruction inquiry as a path to teacher empowerment. Bristol, PA: • Ask about the teacher's rationale for The Falmer Press. her or his instructional approach/es Kretovics, J., Farber, K., & Armaline, W. (1991). Reform 3. Reading and Children from the bottom up: Empowering teachers to transform schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 73, 295 299. • H o w do you think children best learn to Lichtenstein, G., McLaughlin, M. W., & Knudsen, J. read? (1992). Teacher empowerment and professional knowl• What is the difference between good edge. In A. Lieberman (Ed.), The changing contexts of readers and poor readers? teaching. Ninety-first Yearbook of the National Society • D o you feel that all children can learn for the Study' of Education (pp. 37 58). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. to read well? Lightfoot, S. L. (1986). On goodness in schools: Themes of • What is the most important thing that empowerment. Peabody Journal of Education. 63, 435 you do as a teacher to help children 446. learn to read? Maeroff, G. I. (1988). The empowerment of teachers." Overcoming the crisis of confidence. New York: Teacher's 4. Childhood (home or school or both) College Press. • D o you think that there were childhood Midgley, C., & Wood, A. (1993). Beyond site-based experiences that had an impact on you management: Empowering teachers to reform schools. which led to your development as an Phi Delta Kappan, 75, 245 252. Prawat, R. S. (1991). Conversations with self and settings: empowered teacher? (If so, tell me A framework for thinking about teacher about those experiences.) empowerment. American Educational Research 5. Education Journal, 28, 737 757. • Bachelor's Degree--Where--When-Slavin, R. E. (1987). Cooperative learning: Student teams. Memories of training in area of reading Washington, DC: National Education Association. Thomas, K. F., Barksdale-Ladd, M. A., & Jones, R. A. instruction (1991). Basals, teacher power, and empowerment: A • D o you think that there were expericonceptual framework. In J. Zutell & S. McCormack ences during your Bachelor's program (Eds.), Learner factors/teacher factors." Issues in literacy which led to your development as an research and instruction (pp. 385-397). Chicago, IL: 178 MARY ALICE BARKSDALE-LADD and KAREN F. THOMAS empowered teacher? (If so, tell me about those experiences.) • Master's Degree--Where--When-Memories of training in area of reading instruction • Do you think that there were experiences during your Master's program which led to your development as an empowered teacher? (If so, tell me about those experiences.) • Any other formal education experiences which had an impact on your development in becoming empowered? (If so, tell me about those experiences.) • Are there any informal educational experiences which have had an impact on your development in becoming empowered? (If so, tell me about those experiences.) 6. Teaching • Number of years experience • What experiences during your life as a classroom teacher have led you toward empowerment? • Have there been particular individuals-individuals you have taught with, individuals you have taken courses from, individuals away from the school 'setting, or authors whose work you have appreciated, who have had a big impact on your development as a teacher? Tell me about your relationships with these people, or how they had this impact on you. Do you have colleagues who have been particularly supportive of you as a teacher and who may have supported your development as a teacher? Tell me about your relationships with these people. To what degree do you think that these supportive relationships have had an impact on the development of empowerment for you? I've asked a lot of questions about experiences that may have supported the development of empowerment for you. Are there areas in which you feel that you are not empowered? How do you feel about this? Are there experiences or aspects of your life which have tended to keep you from becoming empowered? (If so, what were they, and describe them for me.) Submitted 16 November 1994 Accepted 8 June 1995