DELIVERABLE NUMBER: 2.3

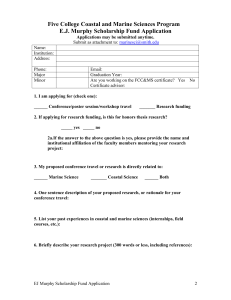

advertisement