DEVELOPMENT OF A COMMUNITY EDUCATION PLAN FOR URBAN WHITE-TAILED DEER MANAGEMENT by

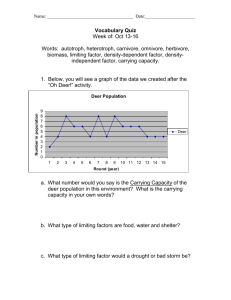

advertisement