Winthrop University’s Institutional Assessment Plan and Guide

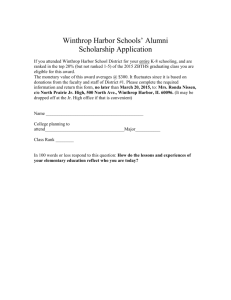

advertisement