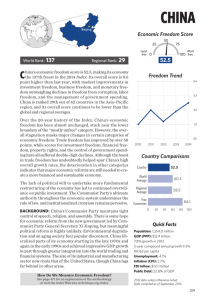

Working Paper Corruption and International Valuation: Does Virtue Pay?

advertisement