Does Food Aid Stabilize Food Availability?

advertisement

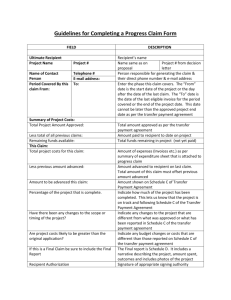

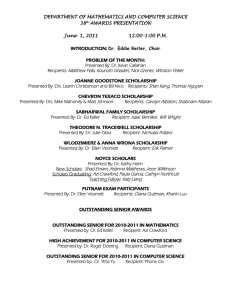

Does Food Aid Stabilize Food Availability? Christopher B. Barrett Associate Professor Department of Agricultural, Resource and Managerial Economics 351 Warren Hall Cornell University Ithaca, NY 14853-7801 Tel: 607-255-4489 Fax: 607-255-9984 Email: cbb2@cornell.edu Http://www.cals.cornell.edu/dept/arme/staff/cbb2/ August 1999 revised version I thank Rob Paarlberg, Tom Reardon, Terry Roe, T.N. Srinivasan, seminar audiences at Cornell and North Carolina State, and participants at the June, 1998, International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium and the Center for International Food and Agricultural Policy symposium on “Policy Reform, Market Stability, and Food Security,” held in Alexandria, VA, for helpful comments. Shane Sherlund provided excellent research assistance, and Ray Nightingale and Joel Greene graciously made data available. Any remaining errors are mine alone. © Copyright 1999 by Christopher B. Barrett. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Does Food Aid Stabilize Food Availability? Abstract: This paper explores the empirical relationship between U.S. food aid flows per capita and nonconcessional food availability per capita in PL480 recipient economies. The evidence suggests PL480, while perhaps modestly progressive in its distribution, fails to stabilize food availability in recipient economies. Both increased domestic food production – i.e., agricultural development – and commercial trade appear more effective than food aid in increasing and stabilizing food availability per capita in lowincome economies. JEL Codes: Q1, O1, F1 1 Does Food Aid Stabilize Food Availability? Food production is notoriously volatile, especially in low-income economies relatively dependent on rainfed agriculture. Given reasonably stable per capita consumption requirements and little interannual grain inventories carryover in poor countries, fluctuations in domestic per capita production lead to highly variable annual import volume requirements in food importing nations. Trade is the principal means for international food distribution at the macro level. But poorer countries often lack the foreign exchange necessary to purchase commercially all the food needed to meet their population’s nutritional requirements. Food aid is therefore often seen as a way to cope with variable food import requirements and restricted commercial import capacity in low-income economies. While aggregate food availability is insufficient to ensure either access to or proper utilization of nutrients to achieve food security (Sen 1981, Barrett forthcoming), aggregate availability is nonetheless a necessary condition for food security. Food insecurity is inevitable within an economy lacking enough food to satisfy all its population’s nutritional needs, even if distributed perfectly equitably and without loss to spoilage or waste. Ensuring adequate aggregate food availability has been, and remains today, a serious challenge in much of the low-income world. Average per capita daily energy and protein availability of 2244 kilocalories and 54.9 grams, respectively, 1961-95 in the low-income economies fell below international recommended nutrient intake levels ( WHO 1985, FAO 1999). Even today, a majority of the low-income countries have per capita daily energy availability of less than 2500 kilocalories, signaling that availability remains an issue in advancing 2 universal access to sufficient and appropriate food. The basic logic of food aid for food security is therefore simple. In so far as food aid is meant to address food availability shortfalls that might cause undernutrition, food aid should flow in response to such shortfalls.1 This raises the question of how one defines a food availability shortfall. In this paper I use each of two reasonable alternatives. A shortfall in cross-section reflects scarcity relative to others. A shortfall in time series reflects scarcity relative to trend availability. Food aid for security should therefore flow disproportionately to countries exhibiting low per capita nonconcessional food availability (NA) — a cross-sectional shortfall — a sharp negative deviation from trend NA — a time series shortfall — or both. But food aid in fact flow to recipient economies in such a manner? That is the question tackled in this paper, as I explore the empirical relationship between food aid flows per capita from the United States’ PL480 programs and nonconcessional food availability per capita in PL480 recipient economies. If food aid indeed stabilizes food availability, then per capita food aid flows should be inversely related to recipients’ per capita nonconcessional food availability, in terms of levels, deviations from trend, or both. This is an empirically testable hypothesis that, to the best of my knowledge, has not yet been studied. Nonconcessional Food Availability Trends in PL480 Recipient Economies Let me begin with some definition of terms and data description. Because individual physiology drives nutritional needs, and in order to be able to compare countries with vastly different human populations, all figures reported are in per capita terms. In order to work with readily comparable series without introducing serious aggregation bias problems, I use cereals volumes to proxy total food production, nonconcessional availability (production plus commercial imports), and 3 aid flows per capita.2 Annual production, commercial import, and population data, 1961-95, were provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, while disaggregated (by year, commodity, Title, and recipient country) PL480 food aid flows data were obtain from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service. The data cover 124 different recipient economies, representing all PL480 recipients during the period other than Japan and developed European economies.3 For those countries that achieved independence after 1961, only independence-era data are used, yielding an uneven panel of data. The food available to feed a country’s residents comes from one of four sources: domestic production, domestic inventories, commercial imports from abroad, or food aid inflows from abroad. This paper looks at how the latter source, food aid, covaries with the first three — which together make up the category nonconcessional food availability (NA) — in order to establish whether food aid helps stabilize aggregate food availability. A data problem emerges immediately. Reliable cereals inventories data are unavailable for most countries, particularly poorer food aid recipients. But since interannual cereals stocks per capita are generally quite small in developing countries,4 the unrealistic limiting assumption used here — that per capita inventories equal zero — probably has little effect on the forthcoming analysis. I should also point out that I do not include total food aid flows from all donors; the analysis considers only PL480 shipments from the United States. But since PL480 comprised about two-thirds of global food aid, 1961-95, the data used here should capture the basic patterns prevailing more broadly. Own production and commercial trade account for the vast majority of cereals availability in PL480 recipient nations. Pooling across years and recipients, domestic production’s mean (median) proportion of aggregate national cereals availability, defined as production plus commercial imports 4 plus PL480 receipts, was 69.3 (80.2) percent.5 Mean (median) commercial imports accounted for another 28.6 (17.6) percent of recipient country food availability, leaving only a tiny fraction covered by PL480 shipments most years in most recipient countries, as can be seen in Table 1 and graphically in Figure 1. Given that PL480 flows rarely comprise more than a negligible proportion of total food availability in recipient countries, this suggests that food aid can play, at best, a very limited stabilizing role. The meagerness of food aid is only one reason for its limited efficiency, however. Even modest amounts of food aid could have a significant effect if targeted and timed well. The 1961-95 Green Revolution era of rapid biochemical improvements to cropping systems, brought unprecedentedly rapid annual average growth of 0.5 percent in global cereals production per capita (Barrett forthcoming). PL480 recipients, however, lagged significantly behind. Annual average growth rates in production and NA for each PL480 recipient, 1961-95, were estimated by equations (1) and (2), respectively. ln(PRODUCTIONt)="0P+"1P YEAR+,Pt (1) ln(NAt)="0N+"1N YEAR+,Nt (2) Across the 124 PL480 recipients, the median annual growth rate in per capita cereals production was -0.2 percent, i.e., more than half (53%) the countries suffered negative average annual growth. The voluminous literature on food aid emphasizes its potential disincentive effects on recipient country production, and perhaps the sluggish growth in recipient production reflects this (Maxwell and Singer 1979; Ruttan 1993; Barrett forthcoming). Rapid growth in PL480 recipients’ commercial cereals imports has made up for sluggish cereals production growth. The median annual growth rate in per capita nonconcessional cereals availability was 0.5 percent, the same as the global growth rate in per capita cereals production (and 5 therefore global NA). Still, more than one-third (37%) of the countries exhibit negative average annual growth even in NA. While the trends are informative, the variability around trend NA is of at least as much interest, in that this reflects short-run instability in food supplies to which food aid is supposed to at least partly respond if it is to serve food security objectives. The estimated standard errors of the residuals of equations (1) and (2), e8 Pt and e8Nt ,6 capture this interannual variability around trend production and nonconcessional availability, respectively. In the next section, I study the empirical relationship between PL480 flows and e8Nt in order to test whether PL480 flows stabilize food availability (i.e., covary negatively with shocks to trend nonconcessional food availability). But first, let’s quickly look more carefully at the regression results from equations (1) and (2). Among PL480 recipients there exists a negative univariate relationship between the average annual growth rate and the standard deviation around trend cereals production per capita. Let vP be the standard deviation of the e8Pt series and vN be the standard deviation of the e8Nt series. Regressing vP on a81P and an intercept term yields a coefficient estimate of -0.914 (with a standard error of the estimate of 0.465).7 This crude result supports the intuitive hypothesis that faster growth in cereals productivity tends to bring with it greater stability around trend per capita production. Put differently, agricultural development appears important not only to increasing developing countries’ food availability but also to stabilizing food availability. Moreover, because production makes up the bulk of countries’ food availability (Figure 1), domestic food production drives nonconcessional food availability. The simple ordinary least squares regression of the annual average growth rates in PL480 recipients’ nonconcessional cereals availability, a81N , on production per capita, a81P , shows that the two are positively and statistically 6 significantly related, as one would expect.8 The statistically significant, sub-unit (0.644) estimated coefficient also reflects the effective role that commercial international trade plays in stabilizing food availability in developing countries. NA responds at less than a one-for-one rate to changes in domestic production. Commercial trade’s stabilizing effect is also reflected by the fact that vN<vP in more than 80 percent of the sample recipients. The mean reduction in the standard deviation of per capita cereals volumes is greater than eight percent per annum, from v2 P = 0.237 to v2 N = 0.156. Commercial food trade contributes significantly to the stabilization of food availability in developing countries. While commercial cereals trade plays a crucial role in stabilizing food availability in low- and middle-income countries, binding foreign exchange constraints nonetheless commonly limit the capacity of poorer countries to dampen food supply volatility through commercial markets. At 15.6 percent, the standard deviation of NA per capita in PL480 recipients remains more than three times the world standard deviation around trend of 4.7 percent. Indeed, 122 of 124 PL480 recipients evince more variable NA than the global rate (all except Georgia and Russia). Given the residual need for food consumption smoothing in developing countries, the core question remains: have PL480 food aid shipments helped to stabilize food availability in the face of extraordinary variability in recipients’ nonconcessional food availability? Put differently, how effectively has PL480 targeted food insufficiency at the national level? PL480 Responsiveness To Need: An Empirical Analysis PL480 flows have dominated global food aid since the program’s inception in 1954. At risk of some oversimplification, there are two basic types of PL480 food aid: program (Titles I and III) 7 and emergency (Title II). The operational distinction between them is perhaps best reflected by the division of responsibility over PL480 between executive branch agencies. Title II PL480 distributions are directed by the U.S. Agency for International Development with an expressed objective of development and relief. Other PL480 distributions are handled by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which also aims to promote U.S. food exports, and in the era of generous crop price support programs used to use food aid to dispose of considerable government-held food inventories. A primary reason to examine PL480 flows disaggregated between program and emergency assistance is the popular belief that Title II flows are more responsive to need, particularly to short-term instability in recipient country NA. Yet program food aid has long dominated PL480 flows. Between 1954 and 1995, Titles I and III of PL480 accounted for better than 80 percent of the more than 300 million metric tons of U.S. food aid and more than half of total worldwide food aid flows. That said, program (emergency) food aid has steadily diminished (grown) in importance over the past twenty years. Program flows averaged 86% of PL480 deliveries and were at least 80% each year prior to 1973, but averaged only 72%, 1973-95, and were above 80% only 3 of those 23 years. Title II shipments surpassed Title I flows for the first time only in 1993. There are at least five interrelated reasons to be skeptical about the effectiveness of PL480 food aid in dampening variability in recipient country food availability. First, previous studies have shown US food aid has been driven largely by considerations other than food security, with relatively little targeting toward countries with pronounced food deficits (Ruttan 1993, 1995; Ball and Johnson 1996, Barrett forthcoming). Surplus disposal and trade promotion objectives and especially geopolitical considerations have largely dominated food aid’s history. Political objectives tend to trump food security concerns in Washington. Second, and related to the first, PL480 flows have 8 shown far greater persistence over the years than is consistent with the claim that they respond to transitory nonconcessional food availability shortfalls in recipient countries (Barrett 1998, Barrett et al. 1999). Third, PL480 flows — indeed bilateral flows more generally — have proved procyclical in aggregate, not countercyclical, because they are budgeted in monetary rather than volume terms (Barrett forthcoming). When world market prices are high, recipient country commercial imports fall and food aid needs grow, but food aid volumes also fall because the budget covers only a smaller volume at a higher price. Fourth, food aid is not fully additional, meaning that food aid receipts consistently replace 60-80 percent of the commercial food imports recipient economies would have made (Von Braun and Huddleston 1988, Barrett forthcoming). Such fungibility necessarily limits the efficacy of food aid in stabilizing food availability. Fifth, until quite recently few good early warning systems existed to anticipate emergencies accurately, so food aid deliveries are largely reactive and therefore often ill-timed. Of these five concerns, only the latter situation may be improving significantly in the case of PL480, although early warning systems continue to have a spotty performance record (Barrett forthcoming). The simplest way to establish whether food aid dampens the variability of recipient country food availability is to estimate the empirical relationship between food aid flows per capita, FA, and both the levels, NA, and the deviations from trend NA , e8N , from equation (2). If food aid flows to those most in absolute need, as reflected by a negative correlation between PL480 and NA levels, then food aid can be described as progressive. If food aid responds negatively to deviations from national trend NA, then FA has a stabilizing, countercyclical effect. The magnitude of the latter relationship is of particular interest as it indicates the compensation proportion, i.e., the proportion of a shortfall that is made up for by PL480 flows. 9 Since FA is a nonnegative variable often taking zero value, this relationship is estimated by the Tobit model: FAit = $0 +$1 e8Nit + $2 NAit + Tit if FAit > 0 (3a) FAit = 0 if FAit = 0 (3b) where i indexes recipient countries and t indexes years. $1 captures the stabilization effect of food aid, while $2 reflects the distributional effect. Since the data are pooled cross-sectional and time series, it is necessary to test first for fixed effects in cross-section, intertemporally, or both. The specification test statistics suggest it is necessary only to control for unobserved region-specific effects.9 A bit later, I consider the results of country- and year-specific estimation of (3) to see whether imposing a universal relationship masks different relations in a nontrivial subsample of countries (it doesn’t). Several interesting results appear in Table 2. The b8 1 and b8 2 estimates are of uniformly low magnitude, most of the b8 1 (b8 2) estimates are positive (negative), and most of the estimates are not statistically significantly different from zero. The low magnitudes reflect in part the negligible contribution of food aid to aggregate food availability in food recipient economies, as suggested earlier by Figure 1. Since the b8 1 coefficient estimates represent compensation proportions the negative and statistically significant b8 2 estimate in the full sample suggests that PL480 has flowed somewhat more to food scarce than food abundant economies, although the associated elasticity, estimated at sample means is only -0.04. There appears to be only very modest global progressivity to PL480 distribution. But the counterintuitively positive signs of the b8 1 estimates suggest that food aid flows have been, if anything, procyclical, not countercyclical on average. In the full sample, one cannot reject at any reasonable level of statistical significance the null hypothesis that PL480 flows 10 are uncorrelated with deviations from recipients’ trend per capita food availability. So while the data weakly support the claim that PL480 has been (modestly) distributionally progressive, they in no way support the claim that PL480 has stabilized food availability in recipient economies. These results hold not only in the full pool of 124 developing country PL480 recipients, but also in three subsamples of particular interest. In the 1960s and into the 1970s food aid — especially program (Title I) PL480 — was disproportionately concentrated on South Asia. For South Asia, home to the largest number of the world’s food insecure, PL480 flows have been statistically significantly procyclical while the estimated progressivity effect is not statistically significantly different from zero. Since the world food crisis of the mid-1970s, PL480 — especially humanitarian (Title II) flows — have been disproportionately focused on Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the only world region in which the proportion of the population suffering food insecurity has not fallen significantly for a generation. PL480 flows to SSA are of particularly low magnitude and statistical significance, and of the wrong (positive) sign to support either the claim that PL480 has stabilized African food availability or the claim that food aid has flowed most generously to those countries most in need. Finally, I also ran the regression for an international group of countries whose PL480 programs (or termination of those programs) are widely recognized as geopolitically motivated. One might suspect that the estimation results from the full sample are contaminated by the inclusion of countries whose PL480 programs have been plainly driven by non-economic and non-humanitarian considerations. The curious result is that while the magnitudes and statistical significance of the parameter estimates are also low, only in this subsample do we get negative point estimates for both b8 1 and b8 2 . So the subset of geopolitically motivated PL480 country programs do not seem to distort the estimation results in the full sample.10 11 The results are also qualitatively unchanged when we reestimate off emergency (Title II) food aid alone or program (Titles I and III) food aid alone, as shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. As shown in the rightmost column of Table 3, only in the case of Title II PL480 to the set of geopolitically motivated recipients does food aid have both stabilization and distributional effects that are statistically significantly negative. PL480 food aid, of any sort, has not stabilized food availability on average in recipient economies, even though its distribution has been modestly progressive on a global -- if not always regional -- scale. So the widespread claim that humanitarian (i.e., Title II) food aid is somehow more responsive to need finds no support in the country-level data, due likely to the factors enumerated earlier. Given the idiosyncracies of PL480 programs in individual recipient countries, and the evolving rhetoric and operational codes of PL480 over 35 years, one might be justifiably skeptical of the results from regressions using data pooled across countries and years. The same qualitative results obtain, however, when one examines the distribution of country- or year-specific estimation results.11 For example, the distribution of country-specific estimates of model (3) shows that most parameter estimates are statistically insignificantly different from zero, extraordinarily few b8 1 estimates are less than -0.1 (which would imply ten percent average compensation effect from PL480 flows) or even statistically significantly negative, and PL480 most commonly flows procyclically around recipients’ food availability trend, not countercyclically (Table 5). The consistency between the patterns found in the distribution of parameter estimates derived from the country-specific time series and the estimated from the pooled sample reported in Tables 2-4 suggests that country-specific differences due to variation in local PL480 operations or recipient country policy do not explain the failure of food aid to stabilize national food availability. 12 Two country examples illustrate how the inefficacy of PL480 in stabilizing food availability arises not just from the small volume of aid flows but also from systematic mistiming (Figure 2). Ethiopia is currently and historically the leading food aid recipient in sub-Saharan Africa. The 1984 famine there drew unprecedented international attention. But PL480 deliveries increased only modestly in 1984 when nonconcessional food availability plummeted. Rather, food aid shipments boomed in 1985 and 1986, when recovery was already well underway. Indeed, the all-time high for per capita PL480 deliveries to Ethiopia was 1986, which was also the second most plentiful year of nonconcessional food per capita in a fifteen year span in Ethiopia! At the national level at least, wellintentioned PL480 shipments arrived when it was least needed. Similarly, Peru is the only country to receive PL480 flows every year since the program’s inception in 1954. In 1994, US food aid flows to Peru more than doubled although nonconcessional food availability in Peru also jumped almost twenty percent that year. By contrast, during the earlier, steady decline in nonconcessional food availability in Peru from 1987-90, PL480 flows also fell steadily. Sen (1981) famously showed that food availability is not sufficient to ensure food security. The empirical evidence analogously suggests decreased (increased) nonconcessional food availability is not sufficient to ensure greater (lesser) PL480 food aid flows to maintain sufficient supplies in low-income countries. Although not reported here, the same basic results obtain in cross-section, in the distribution of year-specific estimates.12 Moreover, the common claim that improvements have been made to PL480 operations based on past lessons learned finds no support in these estimates. There were only five years during the period 1961-95 in which both the b8 1 and b8 2 point estimates were positive in cross-section. Three of the five came in the 1990s, in emergency, program, and pooled PL480 samples alike. So the claim that PL480 distribution meets distributional and stabilization goals more 13 effectively today than in the (Cold War) past finds no support in these data. A final, cautionary note is in order. The macro data used in this analysis cannot capture prospective international or intertemporal variation in the efficacy of intranational food distribution systems in reaching food insecure subpopulations. The analysis reported here necessarily stops at the recipient’s port since the data used are national aggregates. So although these results suggest food aid is ineffective in stabilizing food availability at the macro level, it is theoretically plausible that food aid targeting within recipient economies is so effective that food aid nonetheless stabilizes food availability for particular food-insecure communities, households or individuals. There is certainly anecdotal evidence of emergency food aid distributions proving helpful in averting humanitarian disasters on short notice (Shaw and Clay 1993). There has also been progress in adapting the modalities of emergency food aid delivery, although this seems more true for World Food Programme distributions than PL480 flows (Barrett 1998, forthcoming; Clay et al. 1996). Nonetheless, emergency food aid deliveries are often mistimed, misallocated, or both, sometimes doing more harm than good (Jackson with Eade 1992; Stewart 1998). The only published study of which I am aware that uses micro-level data to investigate community- and household-level food aid targeting finds that food aid flows disproportionately to the most food secure regions and households in Ethiopia (Clay et al. 1999).13 No systematic micro-level evidence seems to exist to demonstrate that even though food aid is remarkably poorly targeted at macro level, it is well enough targeted at micro level to have net positive effects in stabilizing the poor’s access to food. Given the uneven performance of PL480, the evidence presented here puts the burden of proof on those who would claim that PL480 food aid is effectively enough targeted intranationally to overcome its insignificant macro-level effects in stabilizing recipient food availability. 14 Conclusions Improving food security and health and nutritional outcomes around the world will require dampening the extraordinary variability in per capita food availability in low-income economies. Improved food productivity and commercial international trade appear far more useful than PL480 food aid in achieving that objective. The small volumes, opaque allocation mechanisms, and bureaucratically cumbersome procurement procedures behind PL480 have made food aid a relatively ineffective instrument of either stabilization or redistribution. While there are surely particular emergencies and distribution modalities through which food aid can play an effective role in stabilizing and improving food availability at the micro level of individual communities, households, and individuals, commercial trade and more rapid domestic food productivity growth both appear more effective in stabilizing developing national food availability in the regular course of development. Perhaps if food aid were targeted entirely toward relieving food insecurity it could be a more effective instrument. But food aid has long been intensely political, serving many masters. So long as that remains the case, food aid is unlikely to stabilize per capita food availability effectively. 15 References Ball, Richard and Christopher Johnson (1996), “Political, Economic, and Humanitarian Motivations for PL480 Food Aid: Evidence from Africa,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, 44, 3: 515-537. Barrett, Christopher B. (1998), “Food Aid: Is It Development Assistance, Trade Promotion, Both or Neither?” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 80, 3: 566-571. Barrett, Christopher B. (Forthcoming), “Food Security and Food Assistance Programs,” in Bruce L. Gardner and Gordon C. Rausser, editors, Handbook of Agricultural Economics (Amsterdam: Elsevier Science). Barrett, Christopher B., Sandeep Mohapatra, and Donald L. Snyder (1999), “The Dynamic Effects of U.S. Food Aid,” Economic Inquiry, 37, 4: 647-656. Clay, Daniel C., Daniel Molla, and Debebe Habtewold (1999), “Food Aid Targeting in Ethiopia: A Study of Who Needs It and Who Gets It,” Food Policy, 24, 3: 391-409. Clay, Edward J., Sanjay Dhiri and Charlotte Benson (1996), Joint Evaluation of European Union Programme Food Aid: Synthesis Report (London: Overseas Development Institute). FAO, Food Balance Sheets, (online at http://apps.fao.org/). Jackson, Tony with Deborah Eade (1992) Against The Grain: The Dilemmas of Project Food Aid (Oxford: OXFAM). Ruttan, Vernon W. (1993), Why Food Aid? (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press). Ruttan, Vernon W. (1995), United States Development Assistance Policy: The Domestic Politics of Foreign Economic Assistance (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press). Sen, Amartya (1981), Poverty and Famines (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Shaw, John and Edward Clay, eds. (1993), World Food Aid: Experiences of Recipients and Donors (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann). Stewart, Frances (1998), “Food Aid During Conflict: Can One Reconcile Its Humanitarian, Economic and Political Economy Effects?” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 80, 3: in press. Von Braun, Joachim, and Barbara Huddleston (1988), “Implications of Food Aid for Price Policy 16 in Recipient Countries.” Agricultural Price Policy for Developing Countries, edited by John W. Mellor and Raisuddin Ahmed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. World Health Organization (1985), Energy and Protein Requirements: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU expert consultation, Technical Report Series no. 724. 17 Table 1: Shares of Aggregate Cereals Availability PL480 Recipients, 1961-95 Own Production Commercial Imports PL480 Mean 0.693 0.286 0.021 Median 0.803 0.176 0.002 Std. Deviation 0.294 0.286 0.047 Maximum 1.000 1.000 0.644 Minimum 0 0 0 18 Table 2: Tobit Regression Results, All PL480 (Titles I, II, and III) All 124 Countries South Asia Sub-Saharan Africa Geopolitically Motivated $1 (stabilization effect) 0.001 (0.004) 0.038 (0.012) 0.001 (0.002) -0.008 (0.010) $2 (distributional effect) -0.029 (0.010) -0.029 (0.037) 0.014 (0.012) -0.008 (0.029) ln(L) -553.0 -231.6 -319.6 -188.0 n 3838 210 1453 880 Standard errors in parentheses. Tobit regressions including regional dummy variables to control for fixed effects. Regions included are Central Africa, Central America, East Africa, East Asia, Europe, Middle East, North Africa, North America, South America, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Southern Africa, former USSR, West Africa, West Asia, and former Yugoslavia. South America is the base for the global model, West Africa is the base for the Sub-Saharan Africa model, and Europe is the base for the geopolitically motivated model. No fixed effects were found in the South Asia model. South Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Sub-Saharan Africa: Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Canary Islands, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zaire, Zambia, Zimbabwe. Geopolitically Motivated: Afghanistan, Belarus, Bosnia, Cyprus, Dominican Republic, Egypt, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Gaza Strip, Haiti, Honduras, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Korea, Laos, Lebanon, Nicaragua, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Taiwan, Ukraine, Vietnam, Zaire. 19 Table 3: Tobit Regression Results, Emergency (Title II) PL480 All 124 Countries South Asia Sub-Saharan Africa Geopolitically Motivated $1 (stabilization effect) 0.001 (0.001) 0.002 (0.002) 0.001 (0.001) -0.00003 (0.001) $2 (distributional effect) -0.006 (0.001) -0.008 (0.007) 0.005 (0.004) -0.009 (0.004) ln(L) -2299.2 -385.4 -619.4 -823.7 3838 210 1453 880 n Standard errors in parentheses. Same notes apply as on Table 2. Table 4: Tobit Regression Results, Program (Titles I and III) PL480 All 124 Countries South Asia Sub-Saharan Africa Geopolitically Motivated $1 (stabilization effect) 0.0004 (0.004) 0.037 (0.011) 0.001 (0.002) -0.008 (0.009) $2 (distributional effect) -0.025 (0.009) -0.023 (0.035) 0.009 (0.009) -0.003 (0.027) ln(L) -623.8 -240.9 -374.7 -206.3 n 3838 210 1453 880 Standard errors in parentheses. Same notes apply as on Table 2. 20 Table 5: Descriptive Statistics of Country-Specific Tobit Regression Results All PL480 Title II only Titles I and III only Stabilization effects: $1 >0 (%) 67.7 67.6 71.8 Reject H0: $1=0 (%) 26.6 28.8 43.5 6.4 8.9 9.9 10th percentile $1 -0.084 -0.002 -0.074 Median $1 0.014 0.004 0.008 90th percentile $1 0.152 0.055 0.345 Distributional effects: $2 >0 (%) 36.3 30.6 56.4 Reject H0: $2=0 (%) 17.7 17.1 34.6 11.3 11.7 24.3 10th percentile $2 -0.091 -0.034 -0.187 Median $2 -0.008 -0.003 -0.012 90th percentile $2 0.074 0.017 0.088 124 111 78 o/w $1 <0 (%) o/w $2 <0 (%) n 21 Figure 1 Cumulative Frequency Aggregate Cereals Availability Shares PL 480 Recipients, 1961-95 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 0.0 0.2 PL480 0.4 0.6 Proportion Production 0.8 Comm. Imports 1.0 22 Figure 2: Comovement in PL480 and Nonconcessional Food Availability 23 Endnotes 1. Since food aid has traditionally been a macro or sectoral policy instrument, distributed mainly on a government-to-government basis, its relationship to aggregate food availability is an important question, albeit not the only important question surrounding food aid. For broad surveys, see especially Ruttan (1993), Shaw and Clay (1993), and Barrett (forthcoming). 2. Cereals accounted for more than 60 percent of calories and protein in low-income countries, 1961-95, and are by far the single largest source of macronutrients in all low and middle-income countries today (FAO 1999). 3. The only 1961-95 PL480 recipients omitted from the data set are Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Malta, and Spain. 4. While on-farm storage for autoconsumption is considerable, if largely unmeasured, the limited available evidence indicates the vast majority of these stocks are consumed within the year (Sahn 1989). 5. Note that this “aggregate” cereals availability figures omits both food aid receipts other than PL480 shipments and domestic cereals inventories, although these are both relatively small volumes. 6. I distinguish unbiased, consistent regression estimates from the true but unknown population parameters by using Roman rather than Greek letters and the caret (8) symbol. 7. Unlike, cereals production, NA variability and growth rates are unrelated in the set of PL480 recipient economies. 8. The OLS regression result is: a81N = -0.006 + 0.644 a81P (0.102) 9. Using the general model form FAit=$0 +$1 e8it +$2 NAit +3j *j REGIONjit +3t (t YRit + Tit if FAit > 0, likelihood ratio tests of the joint restrictions *j =0 œ j, (t =0 œ t, or both yield test statistics that uniformly support rejecting the null hypothesis of *j =0 œ j at any level of statistical significance for program, emergency, or all PL480 aid, and uniformly fail to support rejecting the null hypothesis of (t =0 œ t at even the ten percent significance level for program, emergency, or all PL480 flows. Test details are available from the author by request. 10. The qualitative results in the rightmost column of Table 2 are robust to each of the several combinations of countries tried in the “geopolitically motivated” set. 11. In estimating the country-specific time series, the regression residuals were subjected to diagnostic portmanteau statistics for autocorrelation. In those instances where autocorrelation was evident, appropriate correction was made using Box-Jenkins techniques. 24 12. A table presenting these results is available from the author by request. 13. Note that cross-sectional studies like Clay et al. (1999) test only what I term the “progressivity” of food aid distribution. No one appears to have yet studied the dynamic “stabilization” effects at the micro level.