Working Paper WP 2012-04 January 2012

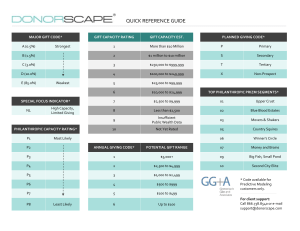

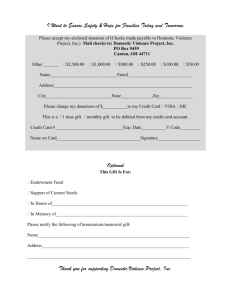

advertisement