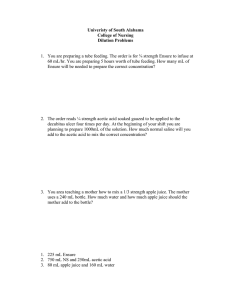

Staff Paper

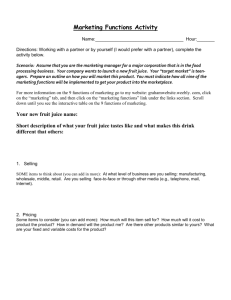

advertisement