FRUIT CONSUMPTION, DIETARY GUIDELINES, AND AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION IN NEW

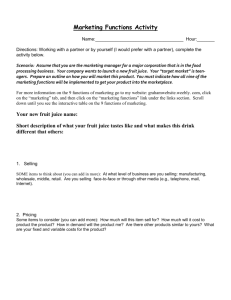

advertisement