Document 11951132

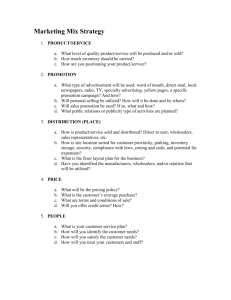

advertisement