Quantitative and Qualitative Measures of Fruit and Vegetable Production in the

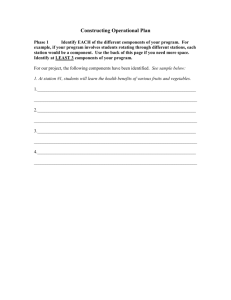

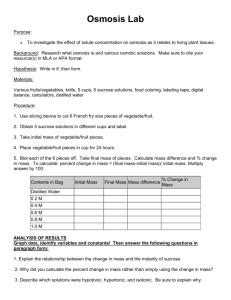

advertisement