U O A ’

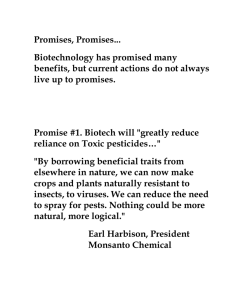

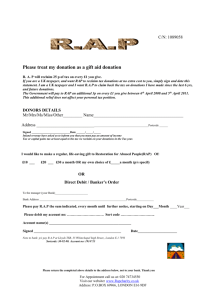

advertisement