Document 11916182

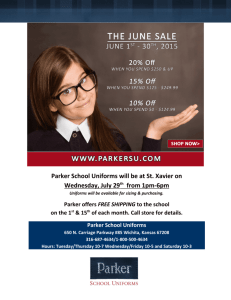

advertisement