The Wisconsin Food Systems Education Conceptual Framework

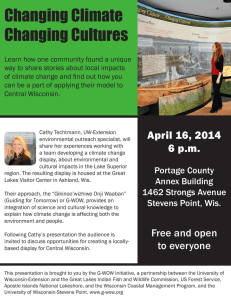

advertisement