Document 11902880

advertisement

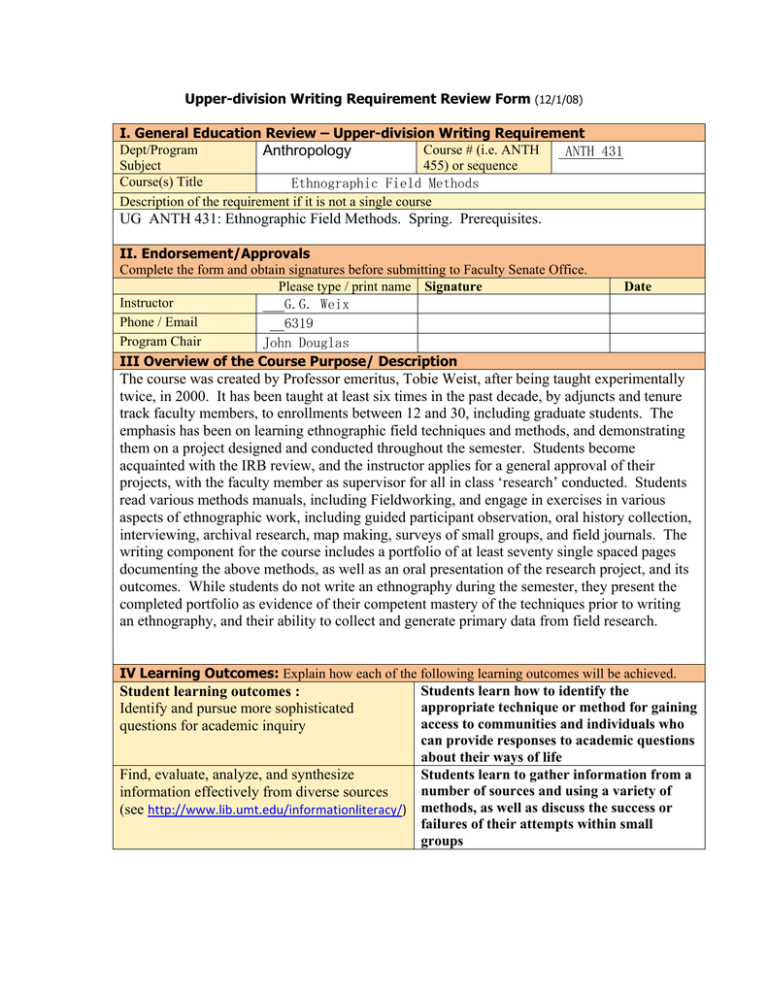

Upper-division Writing Requirement Review Form (12/1/08) I. General Education Review – Upper-division Writing Requirement Dept/Program Course # (i.e. ANTH Anthropology ANTH 431 Subject 455) or sequence Course(s) Title Ethnographic Field Methods Description of the requirement if it is not a single course UG ANTH 431: Ethnographic Field Methods. Spring. Prerequisites. II. Endorsement/Approvals Complete the form and obtain signatures before submitting to Faculty Senate Office. Please type / print name Signature Instructor G.G. Weix Phone / Email 6319 Program Chair John Douglas III Overview of the Course Purpose/ Description Date The course was created by Professor emeritus, Tobie Weist, after being taught experimentally twice, in 2000. It has been taught at least six times in the past decade, by adjuncts and tenure track faculty members, to enrollments between 12 and 30, including graduate students. The emphasis has been on learning ethnographic field techniques and methods, and demonstrating them on a project designed and conducted throughout the semester. Students become acquainted with the IRB review, and the instructor applies for a general approval of their projects, with the faculty member as supervisor for all in class ‘research’ conducted. Students read various methods manuals, including Fieldworking, and engage in exercises in various aspects of ethnographic work, including guided participant observation, oral history collection, interviewing, archival research, map making, surveys of small groups, and field journals. The writing component for the course includes a portfolio of at least seventy single spaced pages documenting the above methods, as well as an oral presentation of the research project, and its outcomes. While students do not write an ethnography during the semester, they present the completed portfolio as evidence of their competent mastery of the techniques prior to writing an ethnography, and their ability to collect and generate primary data from field research. IV Learning Outcomes: Explain how each of the following learning outcomes will be achieved. Students learn how to identify the Student learning outcomes : appropriate technique or method for gaining Identify and pursue more sophisticated access to communities and individuals who questions for academic inquiry can provide responses to academic questions about their ways of life Students learn to gather information from a Find, evaluate, analyze, and synthesize number of sources and using a variety of information effectively from diverse sources (see http://www.lib.umt.edu/informationliteracy/) methods, as well as discuss the success or failures of their attempts within small groups Manage multiple perspectives as appropriate Recognize the purposes and needs of discipline-specific audiences and adopt the academic voice necessary for the chosen discipline Use multiple drafts, revision, and editing in conducting inquiry and preparing written work Follow the conventions of citation, documentation, and formal presentation appropriate to that discipline Develop competence in information technology and digital literacy Students learn to record in a field journal their observations of others actions and conversations, distinguishing their own perceptions and opinions from that of their subjects Students learn the ethical components of review and oversight to ethnographic field work, including addressing IRB panels, peers, and the subjects themselves in the process of doing field work. Students prepare a portfolio as a summary of primary data for ethnography. While they do not write the ethnography itself, they learn the value of accurate and clear recording of description and interviews. Students learn the ethical and peer reviewed standards for documenting ethnographic observations and conversations Students master various forms of technology used in ethnographic field methods V. Writing Course Requirements Check list Is enrollment capped at 25 students? If not, list maximum course enrollment. Explain how outcomes will be adequately met for this number of students. Justify the request for variance. Are outcomes listed in the course syllabus? If not, how will students be informed of course expectations? Are detailed requirements for all written assignments including criteria for evaluation in the course syllabus? If not how and when will students be informed of written assignments? Briefly explain how students are provided with tools and strategies for effective writing and editing in the major. ■Yes No ■ Yes No ■ Yes No Students write 8-10 pages a week, and hand in the portfolios three times during the semester for review and comment by the instructor. Will written assignments include an opportunity for ■ Yes No revision? If not, then explain how students will receive and use feedback to improve their writing ability. Are expectations for Information Literacy listed in ■ Yes No the course syllabus? If not, how will students be informed of course expectations? VI. Writing Assignments: Please describe course assignments. Students should be required to individually compose at least 20 pages of writing for assessment. At least 50% of the course grade should be based on students’ performance on writing assignments. Clear expression, quality, and accuracy of content are considered an integral part of the grade on any writing assignment. Specific techniques are graded, such as formulating an interview, listing questions, conducting, recording, and transcribing the interview, and evaluating the outcome. Informal Ungraded Assignments Students take field notes throughout the semester. VII. Syllabus: Paste syllabus below or attach and send digital copy with form. ⇓ The syllabus should clearly describe how the above criteria are satisfied. For assistance on syllabus preparation see: http://teaching.berkeley.edu/bgd/syllabus.html Formal Graded Assignments Anthropology 431:Ethnographic Methods G.G. Weix P.M. Office: SS 223 238 Tel. 243-6319 ggweix@selway.umt.edu Office hours: MW 2-4 P.M. Class Time: TR 11:10-12:30 Room: SS Course Description Ethnographic methods are not unique to the field of anthropology. Participant observation, daily detailed field notes, interviews and oral histories, and narrative analysis are used by many disciplines, from social sciences (sociology and political science) to humanities (literary criticism and history). However, anthropologists initiated and innovated these techniques of gathering information and gaining new knowledge about human diversity and ways of life. Ethnography means ‘writing about a way of life’ and the primary method of ethnographic projects is fieldwork. This refers to living with and sharing a way of life for an extended period of time. Fieldwork requires continuous residence in chronological time, usually over the course of a year or more in the places described. Ethnographic methods are diverse, and eclectic; anthropologists often reflect upon their tradition of methods in relation to field-based research. The course readings about ethnography and methods focus on technique, justification, and epistemological questions about knowledge of social life and culture. They also address fieldwork ethics, combining field-based and archival research, debates about collaboration and authorial voice, differences of ethnography of small scale and complex societies, the historical legacy of colonialism and post-colonial context for cross-cultural research, and interdisciplinary academic fields and subjects (such as cultural studies) which have extended the visibility of ethnographic methods across the academy. Ethnographic methods can be approached pragmatically as a series of steps and tasks: developing a research question and proposal, stating the relevant theoretical debates, doing library and computer background research, submitting the proposal for human subjects review, planning field-based research, keeping a field journal, developing closed and open questionnaires, interviewing subjects, collecting oral histories, genealogies, or life histories, writing ethnographic field reports, giving an oral presentation of findings, narrative analysis, writing ethnography. One final note: ethnography can include statistical analysis, but often relies more on narrative analysis. Interviews and questionnaires are used to generate text, not a data base. For this reason, we will not be studying social science methods, although a supplemental bibliography is provided. Other courses teaching statistical methods are available in Sociology and Psychology, as well as ANTH 381 and 382: Data Analysis and Advanced Data Analysis. Course Goals and Objectives 1. To learn ethnographic methods, and be able to design and carry out a small project. 2. To learn field-based interviewing and be able to complete a sample of five to ten interviews. 3. To know some of the debates about how ethnographic methods are changing and expanding beyond anthropology into other academic fields. Instructional Method The course meets two times a week for 80 minutes each. Attendance is strongly recommended. Instruction will include short lecture, small group discussion and portfolio and journal work. Individual meetings with the instructor are also strongly encouraged, and email correspondence when appropriate. Course Policies Illness, family emergency, conflicts with other courses’ exams, and athletic participation are all valid reasons to miss class or reschedule assignments and exams. Particularly if you are sick, please stay home until you are well. Because we only meet twice a week, I will consider three absences in a row to be a sign that you are dropping the course. I am available in office hours by appointment for discussion of current topics or to make up assignments. Readings There are three required readings, which we will almost complete by Spring Break. Barrett, Stanley. Anthropology: A Student’s Guide to Theory and Method (Toronto: University of Toronto Press) 1997, 2000. A historical overview of the field of anthropology from the nineteenth century to the present, Barrett discusses the relationship between theoretical paradigms of different eras and the ethnographic methods that emerged, and provides case studies from his own fieldwork projects at home in Canada and abroad (Africa). Messerschmidt, Donald, ed. Anthropologists at home in North America: methods and issues in the study of one’s own society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 1981. A collection of essays from various fieldworkers in Canada and the United States reflecting on the implications of research in their own societies. This book is out of print, and sold as a nonrefundable, but very affordable facpac at the Bookstore. We will read it primarily as case studies of ethnographic projects in North America. Sunstein, Bonnie Stone and Elizabeth Chiseri-Strater. Fieldworking: Reading and Writing Research (Second Edition). (Boston: Bedford Press) 2002. PLEASE NOTE WE ARE READING THE SECOND EDITION. This book has dense, and variegated chapters with readings, explanatory text, exercises and questions, poetry in each section. We will highlight in class the major themes of each section, and I strongly recommend students practice the exercises in their journals for the first half of the course. Evaluation There are no exams for this course, rather, evaluation will be based on portfolios which consist of journals, writing exercises, interview transcriptions, and commentaries on the background literature. There will be two midterm assessments of each student’s progress, March 15th and April 19th at which time portfolios will be turned in and returned on March 25th (after Spring Break) and April 23rd. Final submission of portfolios is May 10th There is no final exam for this course. Grading Criteria and Standards Enclosed on separate sheet. I ask students to write their own expectations and goals at the beginning of the course, and to respond to the grading criteria enclosed. At the end of the course, each student also writes a brief self-assessment of their writing for the course, and the grade they would assign themselves. I take these into consideration in assigning the final grade. Assignments A series of weekly writing assignments will be kept in a portfolio. Students will also meet with the instructor in office hours at least twice during the semester. Students will keep journals, with at least four entries a week, (and probably more during the second half of the course). The final product will be a portfolio of writing that consists of at least 50-75 pages of field notes, and a summary assessment paper of 10-15 pages. Syllabus Week One (January 29-31) Introductions and Expectations Code of Ethics, Ethnography as a Genre Methodology debates: art or science? Read: Barrett pp. 1-79 Historical Overview and Part I: Building the Discipline Sunstein and Chiseri-Strater, Part I: Understanding Cultures pp. 1-54 Week Two (February 5-7) Journals Background research, journals Read: Barrett, pp. 84-140, Part II: Patching the Foundation Sunstein and Chiseri-Strater, Part II: Understanding Fieldwriting, pp. 55-104 Week Three (February 12-14) Observation Participant /Observation and field notes Read: Barrett, pp. 141-206, Part III: Demolition and Reconstruction Sunstein and Chiseri-Strater, Part III, Understanding Texts, pp. 105-160 Week Four (February 19-21) Description Thick Description Read: Barrett, pp. 207-240 The Challenge of Analysis Sunstein and Chiseri-Stater, Part IV, Locating Culture, pp. 159-216 Week Five (February 26-28) Archives Archiving and Organizing Read: Messerschmidt, Part I-Introduction, pp. 3-28 Sunstein and Chiseri-Strater, Part V, The Spatial Gaze, pp. 217-292 Week Six (March 5-7) Conversations Interviews, Collaboration, Transcription Read: Messerschmidt, Part II, Urban Studies, pp. 29-90 Sunstein and Chiseri-Strater, Part VI, The Cultural Translator, pp. 293-344 Week Seven (March 12-14) The Ethnographer’s Ear Listening and Reflecting Read: Messerschmidt, Part III, Rural Studies, pp.91-152 Sunstein and Chiseri-Strater, Part VII, The Collaborative Listener, pp. 345-416 Spring Break, March 16-24 Week Eight (March 26-28) Fieldworking Read: Messerschmidt, Part IV, Heath Studies Week Nine (April 2-4) Fieldworking Read: Messerschmidt, Part V, Education Studies Week Ten (April 9-11) Fieldworking Read: Messerschmidt, Part VI, Contract Anthropology Week Eleven (April 16-18) Fieldworking Read: Messerschmidt, Part VII Reflections at Home Week Twelve (April 23-25) Fieldworking Student Presentations Week Thirteen (April 30-May 2) Fieldworking Student Presentations Week Fourteen (May 7-9) Fieldworking Student Presentations May 10th Final Portfolios Due. BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR METHODS/431 Agar, Michael H. 1980. The Professional Stranger: an informal introduction to Ethnography. Academic Press. Anderson, Barbara G. 1990. First Fieldwork: the misadventures of an anthropologist. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press. Bernard, H. Russell. 2002. Research Methods in Anthropology. (Third Edition) Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press. Bohannan, Paul and Dirk van der Elst. 1998. Asking and Listening: Ethnography as Personal Adaptation. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press. Chiseri-Stater, Elizabeth and Bonnie Stone Sunstein. 1997. Field Working: Reading and Writing Research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Coffey, Amanda and Paul Atkinson. 1996. Making Sense of Qualitative Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Crane, Julia and Michael V. Angrosino. 1984. Field Projects in Anthropology: a student handbook (second edition). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc. Devereux, Stephen and John Hoddinott, eds. 1993. Fieldwork in Developing Countries. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publications. DeVita, Philip, ed. 1992. The Naked Anthropologist: tales from around the world. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Pub. Co. Emerson, Robert M., et al. 1995. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Frantz, Charles. 1972. The Student Anthropologist’s Handbook. Cambridge: Schenkman Pub. Co, Inc. Freilich, Morris, ed. 1977. Marginal Natives at Work: Anthropologists in the Field. New York: Schenkman Pub. Co. Inc. (John Wiley and Sons). Fetterman, David M. 1998. Ethnography: Step by Step. Second Edition. Applied Social Research Methods Series, vol. 17. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. “A Wilderness Guide: Methods and Techniques.” “ Recording the Miracle: Writing.” and “Ethnographic Equipment.” Grindal, Bruce and Frank Salamone, eds. 1995. Bridges to Humanity: Narratives on Anthropology and Friendship. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press. Gupta, Akhil and James Ferguson, eds. 1997. Anthropological Locations: Boundaries and Grounds of a Field Science. Berkeley: University of California Press. “Discipline and Practice: ‘The Field’ as Site, Method, and Location in Anthropology.” “Spatial Practices: Fieldwork, travel, and the Disciplining of Anthropology.” Passaro, Joanne. “You Can’t take the Subway to the Field!: ‘Village’ Epistemologies in the Global Village.” Hammersley, Martyn. 1992. What’s Wrong with Ethnography? Methodological Explorations. New York: Routledge Press. Henry, Frances and Satish Saberwal, eds. 1969. Stress and Response in Fieldwork. New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston. Kutsche, Paul. 1998. Field Ethnography: A Manual for Doing Cultural Anthropology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Langness, L.L. 1965. The Life History in Anthropological Science. New York: Holt, Rinehard, and Winston. Latour, Bruno and Steve Woolgar. 1986 (1979). Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Lawless, Robert et al, eds. 1983. Fieldwork: the Human Experience. New York: Gordon and Breach Science Pub. Lewin, Ellen and William L. Leap, eds. 1996. Out in the Field: Reflections on Lesbian and Gay Anthropologists. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Lofland, John and Lyn H..1984. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis. Wadsorth Pub. Co. Marcus, George E. 1998. Ethnography through Thick and Thin. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. “Ethnography in/of the World System: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography.” “The Uses of Complicity in the Changing Mise-en-Scene of Anthropological Fieldwork.” “Requirements for Ethnographies of Late-Twentieth-Century Modernity Worldwide.” Peacock, James. 1986. The Anthropological Lens: harsh light, soft focus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pelto, Pertti J. and Gretel H. Pelto. 1984. Anthropological Research: the structure of inquiry. second edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. “Units of observation: emic and etic approaches.”, “Art and Science in fieldwork.”, “Facts or Fictions? Fieldwork relationships and the nature of data.”, and “Locating an Informant.” Rabinow, Paul. 1977. Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco. Berkeley: University of California Press. Ragin, Charles C, et al. 1992. What is a Case?: Exploring the foundations of social inquiry. Cambridge University Press. Rubin, Herbert J. and Irene S. Rubin. 1995. Qualitative Interviewing: the Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Sanjek, Roger, ed. 1990. Fieldnotes: the Makings of Anthropology. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Spradley, James P. 1979. The Ethnographic Interview. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. “Ethnography and Culture.”, “Language and Fieldnotes.”, “Informants.”, “Locating An Informant.”, “Asking Contrast Questions.” and “Writing and Ethnography.” Spradley, James P. 1984. Participant Observation. New York: Holt, Reinhardt, and Winston. Spindler, George, ed. 1970. Being an Anthropologist: fieldwork in eleven countries. New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston Thomas, Jim. 1993. Doing Critical Ethnography. Qualitative Research Methods, vol. 26. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Van Maanen, John. 1988. Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. “Fieldwork, Culture, and Ethnography.”, “In Pursuit of Culture.”, and “Fieldwork, Culture, and Ethnography Revisited.” Vansina, Jan. 1985. Oral Tradition as History. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. Viswesawran, Kamala. 1994 Fictions of Feminist Ethnography. University of Minnesota Press. “Fictions of Feminist Ethnography.” “Defining Feminist Ethnography.” “Feminist Ethnography as Failure.” Wax, Rosalie H. 1971. Doing Fieldwork: Warnings and Advice. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Williams, Rhys Thomas. 1967. Field Methods In the Study of Culture. NewYork: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston. Wolcott, Harry F. 1995. The Art of Fieldwork. Walnut Creek, CA: AtlaMira Press. Wolf, Diane L. ed. 1994? 1996. Feminist Dilemmas in Fieldwork. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Kreisworth, Martin. “Trusting the Tale: The Narrativist Turn in the Human Sciences.” Wolf, Diane. “Situating Feminist Dilemmas in Fieldwork.” Hsuing, Ping-Chun. “Between Bosses and Workers: The Dilemma of a Keen Observer.” Wolf, Margery. “Afterward: Musings from an Old Gray Wolf Supplemental Social Sciences Sources Maier, M.H. 1991. The Data Game: Controversies in Social Science Statistics. M.E. Sharpe Publishers. Weisberg, H.F., J.A. Krosnick and B.D. Bowen. 1989. An Introduction to Survey Research and Data Analysis. Second edition. Scott Foresmann. Articles Allen, Charlotte. 1997. “Spies Like Us: When Sociologists Deceive Their Subjects.” Nov. Lingua Franca. Arendt, Hannah. 1958. “Action.” The Human Condition. Chicago United Publishers. Berger, Peter L., et al. 1988. “Analytic Scheme.” A future South Africa: Visions, Strategies, and Realities. Boulder: Westview Press. Berreman, Gerald. 1972. “Prologue: Behind Many Masks; Ethnography and Impression Management.” Hindus of the Himalayas. Berkeley: University of California Press. Chatman, Seymour. 1970. “Story: Existents.” Story and Discourse. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Desmond, Jane. 1991. “Ethnography, Orientalism, and the Avant-Garde Film.” Visual Anthropology. vol. 4, pp 147-160. Ellen, R.F. 1984. “Ethics in relation to informants, the profession and governments.” Ethnographic research: a guide to general conduct. London: Academic Press. Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn. 1994. “Informed Consent in Anthropological Research: We Are Not Exempt.” Human Organization. vol. 53 n1 Goldman, Lawrence. 1983. “Introduction.” Talk Never Dies. Kristeva, Juila. 1993. “The Speaking Subject is Not Innocent.” Freedom and Interpretation. New York: Best Books. MacKinnon, Catherine A. 1993. “On Human Rights.” On Human Rights. NewYork:Basic Books. Narayan, Kirin. 1993. “How Native is a ‘Native’ Anthropologist?” American Anthropologist.vol. 95. Polkinghorne, Donald E. 1988. “Human Existence and Narrative.” Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences. SUNY Publishing. Rosaldo, Renato. 1975. “Where Precision Lies: ‘The hill people once lived on a hill’.” The Interpretation of Symbolism. NewYork: John Wiley and Sons. p 1-22. Rudi, Ingrid. 1991. “Long Term Fieldwork in Malaysia.” Kaber Seberang. n 22. Shapiro, Ian. et al. June 1992. “The Difference that Realism Makes: Social Science and the Politics of Consent.” Politics and Society. vol. 20 no 2. Wheatley, Elizabeth E., 1994. “How Can We Engender Ethnography With A feminist Imagination?” Women’s Studies International Forum. vol. 17, n4, 403-416.