Adjuvant-carrying synthetic vaccine particles augment the

advertisement

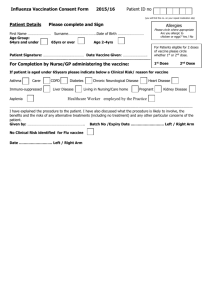

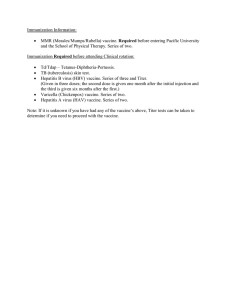

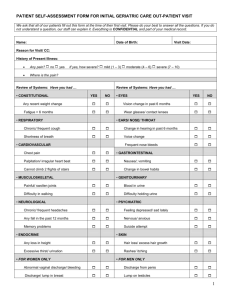

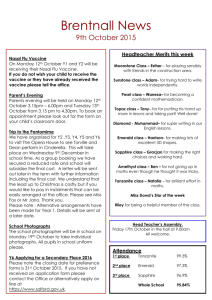

Adjuvant-carrying synthetic vaccine particles augment the immune response to encapsulated antigen and exhibit strong local immune activation without inducing systemic The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Ilyinskii, Petr O., Christopher J. Roy, Conlin P. O’Neil, Erica A. Browning, Lynnelle A. Pittet, David H. Altreuter, Frank Alexis, et al. “Adjuvant-Carrying Synthetic Vaccine Particles Augment the Immune Response to Encapsulated Antigen and Exhibit Strong Local Immune Activation Without Inducing Systemic Cytokine Release.” Vaccine 32, no. 24 (May 2014): 2882–2895. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.027 Publisher Elsevier Version Final published version Accessed Wed May 25 22:15:30 EDT 2016 Citable Link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/91494 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Vaccine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vaccine Adjuvant-carrying synthetic vaccine particles augment the immune response to encapsulated antigen and exhibit strong local immune activation without inducing systemic cytokine release Petr O. Ilyinskii a,∗ , Christopher J. Roy a , Conlin P. O’Neil a , Erica A. Browning a , Lynnelle A. Pittet a , David H. Altreuter a , Frank Alexis b,1 , Elena Tonti c,2 , Jinjun Shi b , Pamela A. Basto d,e , Matteo Iannacone c,2 , Aleksandar F. Radovic-Moreno d,e , Robert S. Langer d,e , Omid C. Farokhzad b , Ulrich H. von Andrian c , Lloyd P.M. Johnston a , Takashi Kei Kishimoto a a Selecta Biosciences, Watertown, MA 02472, USA Laboratory of Nanomedicine and Biomaterials, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, USA c Department of Microbiology and Immunobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA d David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA e Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA b a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Available online 1 March 2014 Keywords: Synthetic nanoparticle vaccine TLR agonist Adjuvant CpG R848 Resiquimod a b s t r a c t Augmentation of immunogenicity can be achieved by particulate delivery of an antigen and by its co-administration with an adjuvant. However, many adjuvants initiate strong systemic inflammatory reactions in vivo, leading to potential adverse events and safety concerns. We have developed a synthetic vaccine particle (SVP) technology that enables co-encapsulation of antigen with potent adjuvants. We demonstrate that co-delivery of an antigen with a TLR7/8 or TLR9 agonist in synthetic polymer nanoparticles results in a strong augmentation of humoral and cellular immune responses with minimal systemic production of inflammatory cytokines. In contrast, antigen encapsulated into nanoparticles and admixed with free TLR7/8 agonist leads to lower immunogenicity and rapid induction of high levels of inflammatory cytokines in the serum (e.g., TNF-␣ and IL-6 levels are 50- to 200-fold higher upon injection of free resiquimod (R848) than of nanoparticle-encapsulated R848). Conversely, local immune stimulation as evidenced by cellular infiltration of draining lymph nodes and by intranodal cytokine production was more pronounced and persisted longer when SVP-encapsulated TLR agonists were used. The strong local immune activation achieved using a modular self-assembling nanoparticle platform markedly enhanced immunogenicity and was equally effective whether antigen and adjuvant were co-encapsulated in a single nanoparticle formulation or co-delivered in two separate nanoparticles. Moreover, particle encapsulation enabled the utilization of CpG oligonucleotides with the natural phosphodiester backbone, which are otherwise rapidly hydrolyzed by nucleases in vivo. The use of SVP may enable clinical use of potent TLR agonists as vaccine adjuvants for indications where cellular immunity or robust humoral responses are required. © 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. Open access under CC BY-NC-ND license. Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; LN, lymph node; ODN, oligonucleotide; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PAP, prostatic acid phosphatase; PO, phosphodiester; PS, phosphorothioate; PRR, pattern recognition receptor; SVP, synthetic vaccine particle; Tfh, follicular helper T cells. ∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 617 231 8118; fax: +1 617 924 3454. 1 2 E-mail address: PIlyinskii@selectabio.com (P.O. Ilyinskii). Current address: Rhodes Research Center, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634, USA. Current address: Division of Immunology, Transplantation and Infectious Diseases, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, 20132 Milan, Italy. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.027 0264-410X/© 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. Open access under CC BY-NC-ND license. P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 1. Introduction Vaccine adjuvants augment the immune response by promoting more effective antigen processing, presentation, and/or delivery [1]. Aluminum salts (alum) were first introduced as vaccine adjuvants over 80 years ago when little was known about the cellular or molecular mechanisms of the immune response [2], yet alum remains the most widely used adjuvant today due to its demonstrated safety profile and effectiveness when combined with many clinically important antigens [3,4]. However, alum is not sufficiently potent to attain protective responses to poorly immunogenic entities [5–9]. Additionally, alum preferentially promotes Th2 type responses [2–4,10], which may exacerbate adverse inflammatory reactions to some respiratory pathogens, such as the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [11], and does not efficiently augment cytotoxic T cell responses, which are necessary to provide protective immunity against many viral antigens or therapeutic immunity against cancer-related antigens [12]. One of the main challenges of current vaccine development is to advance the clinical application of newly developed and potent adjuvants without compromising safety [12,13]. Novel adjuvant candidates have emerged from the discovery of pattern recognition receptors (PRR) that recognize pathogenassociated molecular patterns (PAMP) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) [14–17]. Research on PRRs has provided insight into how the innate system activates and modulates the adaptive immune system [16]. Microbial PAMPs, such as lipopolysaccharides, single-stranded RNA, and bacterial DNA motifs, bind to a family of PRRs called Toll-like receptors (TLR) on innate immune cells and stimulate antigen processing and presentation [16–18]. TLRs are widely expressed on dendritic cells (DC) and other professional APCs such as macrophages and B cells. While some TLRs are expressed on the cell surface and act as sensors for extracellular PAMPs (e.g., lipopolysaccharides), a subset of TLR molecules (TLR3, 7, 8 and 9) are expressed on endosomal membranes and bind nucleic acid-derived molecules, such as single-stranded RNA of viral origin for TLR7 and 8 [19–24] and bacterial unmethylated DNA oligonucleotides (ODNs) containing CpG motifs (CpG ODNs) for TLR9 [14,25–28]. TLR ligands of natural and synthetic origin are potent inducers of innate immune responses and have been shown to effectively stimulate the transition from an innate immune response to an adaptive immune response. As such, TLR agonists have been evaluated as potential adjuvants in a variety of applications [4]. To date, only one PRR ligand, 3-O-desacyl-4 -monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL), a TLR4 agonist, has been included as an adjuvant in a FDA- or EMA-licensed vaccine. MPL adsorbed onto alum is utilized in the HPV vaccine Cervarix, licensed in the U.S. and Europe [29], and the hepatitis B vaccine Fendrix, licensed in Europe [30]. Imiquimod, a topically administered TLR7 agonist, has been approved for treatment of genital warts, actinic keratosis, and basal cell carcinoma [31]. Other TLR agonists, such as poly(I:C) (TLR3), imidazoquinolines other than imiquimod (TLR7, 8, or 7/8), and CpG ODNs (TLR9), have failed thus far to enter clinical practice as parenteral adjuvants despite a multitude of promising data obtained in preclinical and clinical studies [32–36]. One of the main reasons for this failure is the delicate balance between the induction of augmented immunogenicity by TLR agonists and safety concerns, which are often related to the generation of systemic inflammatory responses [19,37–39]. Several groups have utilized micro- and nanocarriers, such as virus-like particles, liposomes, and PLGA particles, to encapsulate adjuvants [40–42]. Encapsulation of adjuvants reduces systemic exposure of adjuvant and enhances uptake by APCs. Nano-size viruses and particles distribute rapidly to the local draining lymph node where they are taken up by subcapsular macrophages and 2883 dendritic cells [41,43,44]. Antigens can also be delivered in particles to target efficient uptake by APCs [36,41,45,46]. Recent studies show that co-encapsulation of both antigen and adjuvant in nanoparticulate carriers have synergistic effects in augmenting immunity by targeting both antigen and adjuvant to the endosomal compartment of APCs [36,42,46]. In this study, we evaluated the immune responses induced by synthetic vaccine particles (SVP) carrying covalently bound or entrapped TLR agonist co-delivered with encapsulated antigen (either in the same or in separate nanoparticle preparations). We hypothesized that such an approach may provide a two-pronged benefit by enabling a focused delivery of antigen and adjuvant and hence enhancing immunogenicity while preventing systemic exposure of the TLR agonist, which can result in excessive systemic cytokine release. Indeed, encapsulation of TLR agonist changed the dynamics of cytokine induction in vitro and in vivo. Systemic cytokine production observed with free resiquimod (R848) was suppressed by its encapsulation within nanoparticles. At the same time, SVP-encapsulated TLR agonists, but not free TLR agonists, promoted sustained cytokine induction in the local draining lymph node as well as a robust infiltration by APCs and, later, by antigen-responsive cells. SVP-encapsulated TLR7/8 and TLR9 ligands augmented humoral and cellular immune responses to both soluble and nanoparticle-delivered protein compared to that observed with free adjuvants. Furthermore, this augmentation did not require co-encapsulation of antigen and TLR agonist in the same SVP. Collectively, these data indicate that SVPs may enable the use of potent TLR agonists as novel adjuvants by targeting their activity to the draining lymph node and minimizing systemic exposure, thereby reducing adjuvant-related side effects. 2. Materials and methods 2.1. Mice Six- to eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA) or Taconic (Germantown, NY, USA). All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by IACUC in accordance with federal, state and city of Cambridge (MA, USA) regulations and guidelines. 2.2. Cells and reagents Fresh murine splenocytes were cultivated in RPMI with 10% FBS and were assayed in 96-well plates at 20,000–50,000 cells/well. Cell lines J774 (murine macrophages), EL4 (H-2b murine thymoma), and E.G7-OVA (EL4 cells transfected with full the length gene encoding chicken OVA) were purchased from the ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) and grown per manufacturer’s recommendations. R848 was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA) or Princeton Global Synthesis (Bristol, PA, USA). Phosphorothioate (PS) or phosphodiester (PO) forms of CpG-1826 (5 -TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT-3 ) were purchased either from Enzo Life Sciences or from Oligo Factory (Holliston, MA, USA). OVA was purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ, USA). Recombinant prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by Virogen (Watertown, MA, USA). Aluminum hydroxide gel (alum) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The poly(lactide) or poly(lactide-co-glycolide) polymers (PLA or PLGA) were purchased from Lakeshore Biomaterials (Birmingham, AL, USA) unless otherwise specified. Poly(lactide)-bl-poly(ethylene glycol) monomethyl ether diblock copolymer (PLA-PEG-OMe) was prepared according to the literature [47,48]. Dichloromethane (CH2 Cl2 ), acetonitrile, HPLC grade water, triethylamine (TEA), and 2884 P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) were purchased from VWR International (Radnor, PA, USA). Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Fluorescamine was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry America (Waltham, MA, USA). Cellgro PBS 1X (PBS) was purchased from Mediatech, Inc. (Manassas, VA, USA). PLGA-R848 polymer was prepared by Princeton Global Synthesis. Polyvinyl alcohol was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). 2.3. SVP preparation and analysis All of the SVP were prepared using a double emulsion water/oil/water system [49]. Briefly, the polymers were prepared at 10% wt/vol in CH2 Cl2 , and OVA was prepared at 50 mg/mL in PBS. In formulations without OVA, we substituted the OVA aqueous phase with PBS. Emulsification via sonication was performed using a Branson Digital Sonifier model 250 equipped with a model 102 C converter and a 1/8 tapered microtip from Branson Ultrasonics (Danbury, CT, USA). Centrifugation was carried out using a Beckman Coulter J-30I centrifuge with a JA-30.50 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The primary emulsion was carried out in a thick walled glass pressure tube with an aqueous to organic phase ratio of 1:5. Following a brief sonication step, Emprove PVA 4–88 aqueous solution was added to the polymer organic solution (at a volume ratio of 3:1 PVA to organic phase), vortex mixed, and emulsified by sonication. The resultant double emulsion was then transferred into a beaker under stirring containing 70 mM phosphate buffer pH 8.0 at a volume ratio of 1 part double emulsion to 7.5 parts buffer. The organic solvent (CH2 Cl2 ) was allowed to evaporate for 2 h under stirring, and the nanoparticles were recovered via centrifugation at 75,600 rcf with two wash steps. PBS was used for the wash solutions and the final resuspension media. The washed SVP suspension was stored at −20 ◦ C. Determination of OVA loading was performed using the fluorescamine test from Udenfriend et al. [50]. R848 and CpG loading were each determined by SVP hydrolysis followed by reversed-phase HPLC analysis. Briefly, nanoparticle solutions were centrifuged, and the pellets were subjected to base hydrolysis to release the adjuvant. R848 hydrolysis was carried out at room temperature using concentrated ammonium hydroxide. Results were quantified from the absorption of R848 at 254 nm using mobile phases comprised of water/acetonitrile/TFA. For CpG analysis, NaOH was used at elevated temperature, with results quantified from the absorption of CpG at 260 nm. The HPLC mobile phases for CpG analysis used acetonitrile/water/TEA. The SVP concentration was determined gravimetrically. Briefly, aliquots of SVP were centrifuged at 108,800 rcf to pellet out the nanoparticles. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was dried (72 h, 37 ◦ C, atmospheric pressure). SVP concentrations were calculated by comparing the weight of the microtube at each of the following steps: empty, with the nanoparticle solution, with the supernatant discarded, and then after the incubator drying step. 2.5. Determination of antibody titers by ELISA 96-Well Costar plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) were coated with 100 l per well of OVA protein (5 g/mL) or prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) protein (1 g/mL; Virogen) and incubated overnight at 4 ◦ C. Plates were washed three times with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS, 300 l diluent (1% casein in PBS; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was added to each well to block non-specific binding, and plates were incubated for at least 2 h at room temperature (RT). Plates were washed as described above, and serum samples were serially diluted 3-fold down the plate and incubated for 2 h at RT. Two columns of standards were included on each plate (anti-OVA monoclonal antibody, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) starting at 0.25 g/mL and diluted 3-fold down the plate. Naive mouse serum was used as a negative control. Plates were washed and detection antibody (either biotinylated goat anti-mouse Ig (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) or horseradish peroxidase (HRP)conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Abcam)) was added to each well. For antibody isotyping, goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) and anti-mouse IgG2c (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA) (both HRP-conjugated) were used. Plates were incubated in the dark for 1 h at RT and washed (three times, with at least a 30-s soak between each wash). For plates with biotinylated antibodies, plates were incubated for 30 min in the dark at RT with streptavidin–HRP (BD Biosciences) and washed (three times, with at least a 30-s soak between each wash). TMB substrate (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was added, and plates were incubated for 10 or 15 min in the dark. The reaction was stopped by adding stop solution (2N H2 SO4 ) to each well, and the OD was measured at 450 nm with subtraction of the 570 nm reading using a Versamax plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data analysis was performed using SoftMax Pro v5.4 (Molecular Devices). A four-parameter logistic curve-fit graph was prepared with the serum dilution on the x-axis (log scale) and the OD value on the y-axis (linear scale), and the half maximum value (EC50 ) for each sample was determined to calculate antibody titer. 2.6. Lymph node preparation for lymphocyte cultivation Four days post s.c. injection with SVP or free antigen (alone or with TLR agonist), mice were sacrificed, draining popliteal lymph nodes aseptically removed and digested for 30 min at 37 ◦ C in 400 U/mL collagenase type 4 (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA). Single cell suspensions were prepared by forcing digested lymph nodes through a 70-m nylon filter membrane, then washed in PBS containing 2% FBS and counted using a Countess® cell counter (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Lymph node derived lymphocytes were then seeded at 5 × 106 cells/mL in 96-well plate (round-bottom) and cultured for an additional 4 days in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat inactivated FBS, 10 U/mL recombinant human IL-2, 50 M 2-ME, and antibiotics (penicillin-G and streptomycin sulphate, both at 100 IU/mL). 2.4. Vaccination Groups of 3–10 mice were injected s.c. in the hind limb with PBS vehicle containing SVP-formulated or free antigens and adjuvants either in both limbs (30 l volume per a single injection site, 60 l total) or in a single limb (60 l total volume). The standard SVP injection dose was 100 g per animal (unless specified otherwise). A single time-point injection was used in cytokine production and T cell induction experiments, and prime-boost regimens (2–3 immunizations with 14 or 28-day intervals; detailed in figure legends) were used in experiments assessing antibody generation. Intranasal inoculation in both nares (60 l total volume) was done at a single time-point under light anesthesia. 2.7. In vitro cytotoxicity OVA specific cytolytic activity in vitro was determined via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release CytoTox96 Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, effector lymphocytes were cultured in limiting dilution either alone or with appropriate target cells, EL4 or E.G7-OVA at 37 ◦ C for 18 h. CTL activity was assessed by measuring relative LDH with maximum and spontaneous release values measured against LDH within supernatants of effector target combinations. Specific lysis was calculated as follows: P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 A 6000 B SVP-R848 R848, free 140 SVP-R848 R848, free 120 5000 100 4000 α (pg/ml) TNF-α α (pg/ml) TNF-α 2885 3000 2000 80 60 40 20 1000 0 0 1 10 100 1000 10000 0.1 1 10 R848 (nM) SVP-PS-CpG 1826 PS-CpG 1826, free SVP-PO-CpG 1826 PO-CpG 1826, free 1200 10000 SVP-PS-CpG 1826 PS-CpG 1826, free 1000 TNF-α α (pg/ml) α (pg/ml) TNF-α 1000 D C 10000 100 R848 (nM) 1000 800 600 400 200 100 0 1 10 100 1000 10000 CpG 1826 (nM) 0.1 1 10 100 1000 PS-CpG 1826 (nM) Fig. 1. Adjuvant encapsulation in nanoparticles (SVP) results in suppressed TNF␣ induction in murine cells in vitro. SVP containing TLR7/8 agonist R848 (A, B) or TLR9 agonists PO-CpG 1826 (C) or PS-CpG1826 (D) were added to J774 cells (A, C) or fresh mouse splenocyte cultures (B, D) in parallel with free adjuvants in triplicates. The amount of TNF-␣ in culture supernatants was measured 6 h (splenocytes) or 16 h (J774) after incubation. Representative results out of two separate experiments with groups of three mice are shown. percent specific lysis (%) = 100 × [(experimental − T cell spontaneous)/(target max − target spontaneous)]. 2.8. In vivo cytotoxicity OVA-specific cytolytic activity in vivo was determined as described [51] at 6 days after a single immunization. Briefly, splenocytes from syngeneic naïve mice were labeled with either 0.5 M, or 5 M CFSE, resulting in CFSElow and CFSEhigh cell populations, correspondingly. CFSEhigh cells were incubated with 1 g/mL of SIINFEKL peptide at 37 ◦ C for 1 h, while CFSElow cells were incubated in medium alone. Both populations were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and injected into immunized or control animals (i.v., 2.0 × 107 cells total). After 18-h incubation, spleens were harvested, processed and analyzed by flow cytometry. Specific cytotoxicity was calculated based on a control ratio of recovery (RR) in naïve mice: (percentage of CFSElow cells)/(percentage of CFSEhigh cells). Percent specific lysis (%) = 100 × [1 − (RR of cells from naive mice/RR of cells from immunized mice) or 100 × [1 − (RRnaive /RRimm )]. 2.9. Determination of cytokine concentration in sera and culture supernatants Free or SVP-encapsulated TLR agonists were serially diluted in tissue culture medium and added to J774 cells or fresh murine splenocytes. Culture supernatants were collected after 6–48 h and assayed for TNF-␣ and IL-6 by ELISA (BD Biosciences, CA, USA). Local cytokine secretion was determined in culture Fig. 2. Nanoparticle encapsulation of both antigen and TLR7/8 agonist (R848), whether co-encapsulated or in separate particles, results in a higher humoral immune response than utilization of free TLR7/8 agonist and/or free antigen. Groups of 5–10 mice were immunized (3 times, 4-week intervals, s.c., hind limb) with various combinations of SVP-OVA or free OVA and/or SVP-R848 or free R848, as indicated. The same dose of OVA (5.6 g) was used in all experimental groups and the same dose of R848 (6.8 g) was used in all groups in which R848 was administered. Antibody generation was measured by ELISA at the indicated time-points and is presented as log10 of EC50 with standard deviations. 2886 P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 Fig. 3. Nanoparticle encapsulation of both antigen and TLR7/8 agonist (adjuvant) results in higher local and systemic cellular immune responses than utilization of free antigen or adjuvant. A – total draining lymph node (LN) cell count, B – SIINFEKL-positive CD8+ T cells in draining lymph node (absolute numbers – gray bars, left Y-axis; percentage of total CD8+ T cells – hatched bars, right Y-axis), C – flow cytometric analysis of SIINFEKL-positive CD8+ T cells ex vivo, D – flow cytometric analysis of SIINFEKLpositive CD8+ T cells after in vitro expansion, E – in vitro cytotoxic activity of LN-derived cells against OVA-expressing target cells, and F – in vivo cytotoxicity against SIINFEKL-pulsed syngeneic splenocytes. Groups of 3–6 mice were injected (s.c., hind limb) either with SVP-encapsulated or free OVA and/or R848 in combinations indicated. At 4 days after injection, total cells in the popliteal LNs were isolated and counted (A). LN cells were then stained for surface markers either immediately (B, C) or after 4 days of in vitro expansion on IL-2 without feeder/stimulator cells (D). The percentage of antigen-specific CTL stained with SIINFEKL-MHC class I pentamer and anti-CD8 antibody was assessed by flow cytometry (indicated in boxes in C and D; samples from two representative animals shown). In vitro cytotoxic activity was assessed after in vitro expansion of LN cells, as described. The difference between specific (E.G7-OVA transfected targets cells) and non-specific (EL-4 parental cells) cytotoxicity is shown (E). The amount of free or SVP-encapsulated OVA and R848 in g/injection dose is indicated in parentheses. The effector-to-target ratio (E:T ratio) is depicted in the x-axis. In vivo CTL activity (F) was assessed in mice (n = 2–4/group) injected s.c. with SVP-encapsulated or free OVA either alone or with free or SVP-encapsulated R848, as indicated. The total dose of OVA was the same across all treatment groups, and the total dose of R848 was the same for all groups receiving R848. Specific in vivo cytotoxicity was determined as described in Section 2 at 6 days post-immunization. All experiments presented in this figure were run 2–3 times. P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 30000 1800 A 1400 RANTES, pg/ml IFN-γγ, pg/ml SVP-OVA-R848 SVP-OVA SVP-OVA + R848, free B 1600 25000 2887 20000 15000 10000 1200 1000 800 600 400 5000 200 0 0 0 4 24 48 0 72 4 Time after injection (hrs) 140 120 C 120 48 72 D 100 100 IL-1β β, pg/ml IL-12 (p40), pg/ml 24 Time after injection (hrs) 80 60 40 80 60 40 20 20 0 0 0 4 24 48 0 72 4 24 48 72 Time after injection (hrs) Time after injection (hrs) Fig. 4. Local cytokines are induced by SVP-encapsulated, but not free, TLR7/8 agonist R848. Mice were injected s.c. in both hind limbs with either SVP-OVA-R848, SVP-OVA, or SVP-OVA admixed with free R848. At the times indicated, popliteal LNs were taken and incubated in vitro overnight. Culture supernatants were collected and analyzed for the presence of specific cytokines by ELISA. A – IFN-␥, B – RANTES, C – IL-12(p40), D – IL-1. Average of four LNs per time-point is shown. Table 1 Local lymphadenopathy induction by administration of SVP-encapsulated but not free TLR7/8 agonist. Table 2 Local lymphadenopathy after administration of SVP-encapsulated TLR7/8 agonist and antigen in naïve vs. pre-immunized mice. Day SVP-R848 SVP (no adjuvant) SVP (no adjuvant) + R848 0 1 4 7 1.00 1.50 3.19 8.06 1.00 1.36 1.53 1.53 1.00 1.08 1.03 0.84 Mice were injected subcutaneously (hind limb) with SVP-R848, SVP (no adjuvant) or SVP (no adjuvant) admixed with free R848. Popliteal LNs were taken at various times as indicated. Total lymph node cells (normalized to day 0 values) in all groups (average of 3 mice per time-point) are shown. supernatants after brief in vitro incubation of draining lymph nodes (LNs) from immunized animals. Briefly, popliteal LN were harvested at different intervals after injection of SVP, free TLR agonist, or PBS and were incubated individually (complete LN, without processing) for 16 h in 300 l of supplemented RPMI-1640 with FBS as described above. Culture supernatants were then assayed Day SVP-R848, total cells in LN 0 3 8 14 21 Naïve mice Immune mice 1.00 4.33 8.04 5.36 4.14 1.00 10.14 9.86 6.93 6.60 Naive or previously immunized mice were injected with SVP-R848 with coencapsulated antigen (hind limb, s.c.). Popliteal LNs were taken at various times as indicated. Total lymph node cell counts (normalized to day 0 values) in all groups (average of 3 mice per time-point) are shown. for murine cytokines by ELISA using specific kits (BD Biosciences) or by multiplex ELISA biomarker assays (Aushon BioSystems, Billerica, MA, USA). Cytokine levels determined in the cultures from LNs of PBS-immunized animals were used as the initial time-point (0 h). Table 3 Local lymphadenopathy and immune cell population expansion after administration of SVP-encapsulated TLR7/8 agonist. Day Total cells CD11c+ B220− (mDC) CD11c+ B220+ (pDC) B220+ CD11c− (B cells) F4/80+ GR1− (Mø) F4/80− GR1+ (Gran) CD3+ (T cells) CD3− CD49b+ (NK) CD3+ CD49b+ (NKT) 0 1 4 7 1.00 1.50 3.19 8.06 1.00 3.15 6.50 7.00 1.00 1.36 8.14 7.77 1.00 0.98 3.56 11.09 1.000 1.97 1.16 2.51 1.00 3.52 14.20 18.43 1.00 1.52 2.54 4.39 1.00 1.03 9.64 8.57 1.00 0.62 6.72 8.25 Mice were injected s.c. (hind limb) with SVP-R848, SVP (no adjuvant), or SVP (no adjuvant) admixed with free R848. Popliteal LNs were taken at times indicated. Total lymph node cells were counted, stained for various surface markers, as indicated, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cell numbers were normalized to day 0 values. Data shown in table are from SVP-R848 injected mice. No marked variation in LN cell populations was seen in mice injected with “no adjuvant”-SVP or “no adjuvant”-SVP admixed with free R848 (not shown). Mø – macrophages, mDC and pDC – myeloid and plasmacytoid DC, Gran – granulocytes, NKT – NK T cells. P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 2.10. Flow cytometry At different time-points after injection with SVP, free TLR agonist or PBS, mice were sacrificed, draining popliteal lymph nodes harvested and digested for 30 min at 37 ◦ C in 400 U/mL collagenase type 4 (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA). Single cell suspensions were prepared by forcing digested lymph nodes through a 70-m nylon filter membrane, then washed in PBS containing 2% FBS and counted using a Countess® cell counter (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were stained pairwise with antibodies against the following mouse surface cell molecules: B220 and CD11c, CD3 and CD49b, F4/80 and Gr1 (BD Biosciences, CA, USA). The gating logic was as follows: plasmacytoid dendritic cells (CD11c+ , B220+ ), myeloid dendritic cells (CD11c+ , B220− ), B cells (CD11c− , B220+ ), granulocytes (GR-1+ , F4/80− ), macrophages (GR-1− , F4/80+ ), NK T cells (CD49b+ , CD3+ ), NK cells (CD49b+ , CD3− ), and T cells (CD49b− , CD3+ ). Similarly, SIINFEKL-loaded pentamers (Proimmune, Oxford, UK), were used along with anti-mouse CD8 and CD19 (to gate out non-specific pentamer binding). Cell samples were then washed and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA). 18000 14000 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 0 1800 24 4 24 48 144 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 0 3.1. Nanoparticle encapsulation of TLR agonists changes the pattern of inflammatory cytokine induction in vitro 200 TLR7/8 (R848) and TLR9 (CpG ODN 1826; mouse-specific Btype CpG ODN) agonists were encapsulated in synthetic polymer nanoparticles and tested for their ability to induce cytokines in vitro. R848 was chemically conjugated to PLGA and used for SVP formulation as PLGA-R848, and CpG ODN was passively entrapped into SVP as described in Section 2. Natural oligonucleotide sequences contain a phosphodiester (PO) backbone, which is susceptible to rapid hydrolytic cleavage by nucleases in vivo. Nuclease-resistant CpG sequences with a phosphorothioate (PS) backbone have been shown to have superior activity to PO-CpG in vivo. Both PS and PO forms of the immunostimulatory CpG ODN 1826 sequence (PS-CpG 1826 and PO-CpG 1826) were evaluated. SVP-encapsulated R848 induced lower levels of TNF-␣ from splenocytes and especially from murine macrophages than identical amounts of free R848 (Fig. 1A and B). Similar profiles were seen when PS-CpG 1826 and PO-CpG 1826 sequences were tested in free or SVP-encapsulated form. Not surprisingly, PO-CpG 1826 was a less potent inducer of TNF-␣ production than PS-CpG 1826, with its SVP-encapsulated form being nearly inactive, even in the more sensitive J774 cells (Fig. 1C and D). IL-6 production in vitro followed the same pattern as TNF-␣ (data not shown). However, a static in vitro system does not capture potential differences in biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of free adjuvant versus nanoparticle-encapsulated adjuvant that are expected in vivo. 160 The adjuvant activity of nanoparticle-encapsulated R848 (SVPR848) was assessed in vivo in immunogenicity studies with 4 B 1600 3. Results 3.2. Nanoparticle encapsulation of TLR7/8 agonist increases its adjuvant activity while antigen encapsulation increases immunogenicity in vivo SVP-R84 8 (I) R848, free (I) SVP-R848 (C) R848, free (C) A 16000 IFN-γγ , pg/ml Similarly, systemic cytokine levels in pooled or individual serum samples drawn from vaccinated animals via terminal bleeds at different time intervals after inoculation were measured by ELISA. Cytokine levels from the sera of PBS-immunized animals were considered as the initial time-point (0 h). All experiments on cytokine measurement in vivo were run two or three times yielding similar results for each experimental group. IL-12(p40), pg/ml 2888 C β , pg/ml IL-1β 180 48 144 48 144 Time after injec tion (hrs) 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 4 24 Time after injection (hrs) Fig. 5. Focused local cytokine induction after a single-site injection with SVPencapsulated, but not free, TLR7/8 agonist R848. Mice were injected s.c. in a single hind limb with either SVP-R848 or free R848. At the times indicated, popliteal LNs from the injection side (ipsilateral, I) and from the opposite side (contralateral, C) were collected and incubated in vitro overnight. Culture supernatants were analyzed for the presence of specific cytokines by ELISA. A – IFN-␥, B – IL-12(p40), C – IL-1. Average of two mice per time-point is shown. a model antigen, OVA (Fig. 2). The potency of free and SVPencapsulated R848 to induce antibodies to OVA was compared in a standard prime-boost immunization regimen. Both free and nanoparticle-encapsulated forms of OVA were tested (OVA and SVP-OVA, respectively). Additionally, R848 and OVA were either co-encapsulated in the same particle (SVP-OVA-R848) or were admixed as separate particles (SVP-R848 and SVP-OVA). When admixed with soluble OVA, SVP-R848 resulted in nearly a 10-fold P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 2889 16000 800 A SVP-OVA-R848 SVP-OVA SVP-OVA + R848 B 14000 12000 IL-6, pg/ml α , pg/ml TNFα 600 400 10000 8000 6000 4000 200 2000 0 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 3 0 6 0.5 1000 3 6 D 12000 800 10000 IP-10 (pg/ml) RANT ES (pg/ml) 1.5 14000 C 600 400 8000 6000 4000 200 2000 0 0 0 3 6 24 0 48 3 6 24 Time after injection (hrs) Time after injection (hrs) 5000 35000 E F 30000 MCP-1 (pg/ml) 4000 IL-12(p40), pg/ml 1 Time after injection (hrs) Time after injection (hrs) 3000 2000 25000 20000 15000 10000 1000 5000 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 3 6 24 Time after injec tion (hr s) 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 3 6 24 Time after injection (hrs) Fig. 6. Strong systemic cytokine induction after injection of free, but not SVP-encapsulated TLR7/8 agonist R848. Mice were injected s.c. with either SVP-OVA-R848, SVP-OVA or SVP-OVA admixed with free R848 and bled at times indicated. The same amount of free or SVP-encapsulated R848 was used for each group (6.8 g). Serum samples were collected at the times indicated and analyzed for individual cytokines by ELISA. Average cytokine concentration is shown (three samples per group per each time-point). A – TNF-␣, B – IL-6, C – RANTES, D – IP-10, E – IL-12(p40), F – MCP-1. increase in immunogenicity compared to free R848 after two or three injections (Fig. 2). SVP-R848 exceeded the potency of alum, an adjuvant in numerous commercially approved vaccines, by an even higher margin (antibody titer EC50 values for animals immunized with OVA in alum were below the cut-off level for the assay). Notably, the presentation of OVA by SVP also resulted in a marked increase of antibody response (by at least 2–3 orders of magnitude) compared to free OVA with or without alum. Addition of free R848 to SVP-OVA further increased immunogenicity, especially after one or two injections, but its effect was not pronounced after the third vaccination. Free R848 was also inferior to encapsulated R848 whether it was co-encapsulated with OVA (SVP-OVA-R848) or present in a separate particle (SVP-OVA + SVP-R848). On average, co-encapsulation of OVA and R848 led to a 0.5-log increase in antibody titer compared to utilization of free R848, while admixing of SVP-OVA with SVP-R848 was more potent in antibody generation than addition of a free R848 to SVP-OVA by an order of magnitude (Fig. 2). While addition of free R848 to SVP-OVA led to a clear Th1 shift in antibody response after two injections (IgG1:IgG2c ratios of 0.28 vs. 3.13 at day 40 for SVP-OVA + R848 and SVP-OVA, correspondingly), the difference was even more pronounced if R848 was SVP-encapsulated (IgG1:IgG2c ratios of 0.08 for SVP-OVA-R848 and 0.11 for SVP-OVA + SVP-R848). Similarly, nanoparticle-encapsulated OVA and R848 induced strong local and systemic cellular immune responses (Fig. 3). Injection of nanoparticle-encapsulated R848 led to a significant influx of cells into draining lymph nodes (LN) even after a single inoculation (Fig. 3A). Moreover, utilization of encapsulated R848 (whether with free or co-encapsulated OVA) elevated both the percentage and absolute quantities of locally induced antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, as assessed by reactivity with MHC class I pentamers containing the dominant ovalbumin epitope, SIINFEKL (Fig. 3B and C). 2890 P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 250 300 A IL-6, pg/ml 200 TNFα α , pg/ml SVP-OVA-R848 SVP-OVA SVP-OVA + R848 B 250 150 100 50 200 150 100 50 0 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 3 6 0 1 Time after inoculation (hrs) 4000 1.5 3 6 Time after inoculation (hrs) 14000 C D 3000 10000 M CP-1, pg/ml IL-12(p40), pg/ml 12000 2000 8000 6000 4000 1000 2000 0 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 3 Time after inoculation (hrs) 6 0 0.5 1 1.5 3 6 Time after inoculation (hrs) Fig. 7. Systemic cytokine induction after intranasal inoculation of free, but not SVP-encapsulated TLR7/8 agonist R848. Mice were inoculated intranasally with either SVPOVA-R848, SVP-OVA, or SVP-OVA admixed with free R848 and bled at times indicated. The same amount of free or SVP-encapsulated R848 was used for each group (3.8 g). Serum samples were collected at the times indicated and analyzed for individual cytokines by ELISA. Average cytokine concentration is shown (three samples per group per each time-point). A – TNF-␣, B – IL-6, C – IL-12(p40), D – MCP-1. Cells induced by co-encapsulated R848 and OVA exhibited a higher proliferative potential than when either free R848 or free OVA was utilized, as evidenced by in vitro expansion of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3D) and their cytotoxic activity (Fig. 3E). The in vivo cytotoxic activity was assessed at 6 days after a single injection of nanoparticle-encapsulated or free OVA in the presence or absence of free or nanoparticle-encapsulated R848. SIINFEKL-pulsed syngeneic target cells were eliminated efficiently in vivo only if both OVA and R848 were delivered in encapsulated form (Fig. 3F). The level of in vivo cytotoxic activity was maintained for several days after a single injection (data not shown). The admix of nanoparticleencapsulated OVA with free R848 or the admix of free OVA with nanoparticle-encapsulated R848 induced poor in vivo cytotoxic activity (Fig. 3F). 3.3. Rapid infiltration of draining lymph nodes by innate and adaptive immune cells upon injection of nanoparticle-encapsulated R848 R848-bearing nanoparticles induced a profound increase in cellularity within the draining lymph nodes at 4 days after a single inoculation (Fig. 3A). Further analysis of cellularity within the draining lymph nodes after s.c. injection showed that LN infiltration starts as early as 1 day after inoculation, reaches a peak at 7–8 days, and is maintained for at least 3 weeks (Tables 1 and 2). The increase in lymph node cellularity was even more rapid and pronounced in mice that were previously immunized with SVP (10-fold increase in the popliteal LN cell count at 1 day after inoculation, Table 2). No significant cell infiltration of the draining lymph node was seen if SVP lacking R848 were used either alone or admixed with free R848 (Table 1). A detailed analysis of intranodal cell populations after SVP-R848 injection showed a rapid increase in the number of innate immune cells, such as granulocytes and myeloid DC, in the draining LN, with their numbers increasing 3-fold within 24 h after a single injection (Table 3). There was also an early elevation in macrophage cell numbers in the draining lymph node, while increases in other APC subtypes (plasmacytoid DC and B cells) were observed at a slightly later time-point. Interestingly, among the populations analyzed, only effector cells of the adaptive immune response (T and B cells) showed a continued expansion from day 4 to day 7 (Table 3). 3.4. Nanoparticle encapsulation of TLR7/8 agonist induces strong local cytokine production Strong local immune activation by nanoparticle-encapsulated R848 was further manifested by cytokine production in the draining LN milieu (Figs. 4 and 5). At 4 h after subcutaneous injection, high levels of IFN-␥, RANTES, IL-12(p40) and IL-1 were secreted by LNs from animals injected with SVP-OVA-R848, while the production of these cytokines by LNs from mice injected with free R848 was close to the background level (Fig. 4). In particular, the amount of IFN-␥ secreted by LNs from mice injected with SVP-OVA-R848 at 4 h was more than 100-fold higher than that from the LNs of mice injected with SVP-OVA and an equal amount of free R848 (Fig. 4A), while RANTES was elevated more than 27-fold (Fig. 4B). Production of all of these cytokines in the LN was maintained for at least 72 h after injection of SVP-OVA-R848, with levels of IL-12(p40) and IL-1 remaining nearly stable (Fig. 4C and D), and levels of IFN-␥ and RANTES, while decreasing, remaining 4- to 20-fold higher than the background. In contrast, inoculation of free R848 led to only a modest increase of local cytokine production at 4 h, which returned P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 7 Anti-OVA IgG EC 50 (Log10) to background levels by 24 h after administration. Levels of IP-10 and MCP-1 in LNs from SVP-OVA-R848-injected animals were also elevated in a similar fashion (data not shown). The striking difference in local cytokine production after administration of nanoparticle-encapsulated versus free R848 (Fig. 4) was also evident by comparing cytokine production in the ipsilateral draining lymph node versus the contralateral lymph node after injection in a single hind limb (Fig. 5A and B). The sustained expression of IFN-␥, IL-12(p40), and IL-1 was seen in the ipsilateral LN at 4–48 h after injection of SVP-R848, but not in the contralateral lymph node. In contrast, free R848 induced a modest elevation of IL-12(p40) and IFN-␥ in both the ipsilateral and contralateral lymph nodes (Fig. 5B). The level of IFN-␥ observed in the ipsilateral lymph node following injection of free R848 was 50-fold lower than that induced by SVP-R848 (Fig. 5A). No induction of IL-1 by free R848 was seen (Fig. 5C). 2891 Day 26 Day 44 6 5 4 3 VA + SVP-O PO-C SVP- pG VA + SVP-O PS-C pG + OVA PS-C pG B 3.6. Nanoparticle encapsulation of TLR9 agonist permits effective utilization of immunostimulatory phosphodiester CpG ODNs in vivo Day 26 Day 40 6 5 4 3 SVP-OVA + SVP-PO-CpG Day 19 Day 31 C 6 5 4 3 SVP-PAP-PO-CpG We next assessed the adjuvant activity of a nanoparticleencapsulated TLR9 agonist, CpG-1826, in immunogenicity studies with a model antigen, OVA. It is known that a PO form of CpG is subject to rapid degradation by nucleases [36,46] and therefore the backbone-modified PS form is usually employed in vivo. We reasoned that nanoparticle encapsulation may protect the PO form from premature degradation and enable use of PO-CpG in vivo. Co-administration of nanoparticle-encapsulated OVA and PO-CpG 1826 induced antibody titers comparable to that obtained with nanoparticle-encapsulated OVA admixed with the same dose of free PS-CpG 1826 (Fig. 8A). Animals immunized with the same doses of free OVA admixed with free PS-CpG 1826 exhibited 20to 40-fold lower antibody titers (Fig. 8A). Increasing the dose of free OVA and free PS-CpG 1826 did not increase the antibody titers compared to SVP-encapsulated OVA and PO-CpG (Fig. 8B). When another antigen, prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), was evaluated, PS-CpG 1826 was inferior by nearly two orders of magnitude in antibody induction compared to nanoparticle-encapsulated PAP and PO-CpG 1826 (Fig. 8C). Nanoparticle entrapment of PSCpG 1826 did not lead to higher immunogenicity compared to OVA (5x) + PS-CpG (5x) 7 Anti-PAP IgG EC50 (Log10) While nanoparticle encapsulation of R848 enhanced immunogenicity and local induction of immune cytokines, the production of systemic inflammatory cytokines by SVP-R848 was markedly suppressed compared to that observed with free R848 after either subcutaneous or intranasal inoculation (Figs. 6 and 7, respectively). In particular, 4 h after subcutaneous inoculation, serum concentrations of early inflammatory cytokines TNF-␣ and IL-6 were 50–200 times higher if free R848 was used (Fig. 6A and B). Serum cytokine levels were similar in animals inoculated with SVPOVA with or without encapsulated R848. Similar differences were observed with systemic production of RANTES (Fig. 6C). SVP-OVAR848 induced modest levels of IP-10, IL-12(p40), and MCP-1, which were approximately 5–10 times lower than that observed after injection of SVP-OVA admixed with free R848 (Fig. 6D–F). Patterns of systemic cytokine expression profiles after intranasal delivery of either free or encapsulated R848 (Fig. 7) were similar to those seen after s.c. delivery. Serum TNF-␣ and MCP-1 were only weakly induced by SVP-R848, with levels 10- to 100-fold lower than those induced by free R848 (Fig. 7A and D), while levels of IL-6 and IL-12(p40) induction were 5 times lower (Fig. 7B and C). Anti-OVA IgG EC50 (Log10) 7 3.5. Nanoparticle encapsulation of TLR7/8 agonist R848 attenuates the production of systemic inflammatory cytokines A PAP (50x) + PS-CpG (2x) Fig. 8. Higher humoral immunogenicity of SVP-encapsulated antigen coupled with free TLR9 agonist PS-CpG or with SVP-encapsulated TLR9 agonist PO-CpG. Mice (5/group) were immunized (s.c., hind limb) with the indicated SVP or combinations of free antigen and PS-CpG 1826. Antibody titers were determined at times indicated. Mice were immunized either two (A, C) or three (B) times with 2-week intervals between immunizations. OVA (A, B) and prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) (C) proteins were evaluated as test antigens, either in free form or encapsulated in SVP. In Panel B, the total dose of both free OVA and free PS-CpG 1826 was five times greater than that administered in the SVP-treated groups. In Panel C, the amount of free PAP used was 50 times higher than that of SVP-encapsulated PAP, and the amount of free PS-1826 was two times higher than used in SVP-encapsulated form (C). No adjuvant effect of free PO-1826 was detected (data not shown). entrapped PO-CpG 1826, while utilization of free PO-CpG 1826 resulted in no augmentation of immunogenicity (data not shown). When nanoparticle-encapsulated OVA and PO-CpG 1826 were compared to free OVA and free PS-CpG 1826 in their ability to induce specific CTLs in vivo, the combination of the former was more effective even if 10 times more free OVA and 5 times more free PS-CpG 1826 were used (Fig. 9). 2892 P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 Fig. 9. Nanoparticle encapsulation of both antigen and TLR9 agonist PO-CpG (adjuvant) results in a higher local cellular immune response than utilization of free antigen and adjuvant. Groups of 2–3 mice were injected (s.c., hind limb, once or twice with 2-wk interval) with a combination of SVP-encapsulated OVA and SVP-encapsulated PO-CpG 1826, free OVA admixed with free PS-CpG 1826, or PBS as indicated. The amount of free OVA (50 g) was ten times higher and the amount of free PS-CpG 1826 (20 g) was five times higher than that present within SVP (5 and 4 g, respectively). Tissues were taken at 5 days after the last immunization and restimulated in vitro for 7 days with mitomycin-treated E.G7-OVA cells. LN cells were stained with surface marker antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Top row – popliteal LN cultures (initiated 5 days after a single immunization), bottom row – splenocyte cultures (initiated 5 days after prime-boost immunization). Representative flow cytometry dot plots from two separate experiments are shown. The numbers indicate the percentage of CD8+ T cells that are specific for the OVA SIINFEKL peptide (percent share of CD8+ CD19− cells). No significant induction of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-␣, IL6) in serum was seen when free or encapsulated PO and PS forms of CpG-1826 were tested, while free PS-CpG 1826 induced the production of IL-12(p40) to the same levels as nanoparticle-encapsulated PO-CpG 1826 (Table 4). Nanoparticle entrapment of PS-CpG 1826 led to elevated and sustained local production of IFN-␥, IL-12(p40), and IL-1, which exceeded that of free PS-CpG 1826 (used in 10-fold excess, Fig. 10), closely paralleling results seen when free and SVPencapsulated R848 were compared (Fig. 7). No cytokine induction from contralateral LN was observed after SVP-PS-CpG inoculation (Fig. 10). 4. Discussion TLR7/8 and TLR9 agonists have shown great promise as immunomodulating therapeutic agents [52–61; reviewed in 36] and as adjuvants for DNA- [62] and protein-based vaccines [63–67]. Both R848 and CpG ODNs were seen as attractive candidates for systemic use in a variety of settings [see summaries in 12,31,36,40,68] due to TLR7/8 and TLR9 distribution in immune cells and resulting Table 4 Systemic cytokine induction after encapsulated or free TLR9 agonist. subcutaneous administration of SVP- Cytokine peak concentration (pg/mL) Mice injected with TNF-␣ IL-6 IL-12(p40) SVP-OVA SVP-OVA + SVP-PO-CpG 1826 SVP-OVA + PO-CpG 1826 SVP-OVA + PS-CpG 1826 1.4 11.2 2.2 12.8 67.2 105.2 79.6 58.7 43.9 569.4 44.0 448.0 Mice were injected subcutaneously (hind limb) with either SVP-OVA alone or combined with SVP-PO-CpG 1826, free PO-CpG 1826, or free PS-CpG 1826 and bled at 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 3 h after injection. Peak average cytokine concentration in serum is shown (three samples per group for each time-point). ability of these compounds to specifically activate APCs (i.e., dendritic cell, monocyte/macrophage, and B cell populations). However, broad use of TLR7/8 and 9 agonists as parenteral drugs and adjuvants has been limited due to systemic toxicity [13,69], which is directly related to systemic cytokine release [70]. We hypothesized that encapsulation of a TLR agonist into a nanoparticle carrier may attenuate systemic cytokine induction and thus enable its use as a parenterally administered adjuvant. Nanoparticle delivery of TLR7/8 or TLR9 agonists would have multiple benefits, including (1) minimizing systemic exposure of the TLR agonist, (2) delivering of adjuvant to lymph nodes via direct flow of nanoparticles through draining lymphatics [43,44], (3) promoting uptake into endosomal vesicles of APC, where TLR7, 8, and 9 are expressed, and (4) providing a sustained release of the TLR agonist from a nanocarrier rather than a bolus delivery. Moreover, nanoparticle encapsulation of both antigen and adjuvant may have a synergistic benefit by enabling co-delivery of both antigen and adjuvant to APCs as demonstrated earlier for microparticle delivery vehicles [40,46]. R848 is a highly potent TLR7/8 agonist that rapidly distributes throughout the body and exhibits a short half-life [12]. While imiquimod, an analog of R848 which is 100-fold less potent, is licensed as a topical drug for genital warts, actinic keratosis, and basal cell carcinoma [31], clinical development of R848 as a topical drug and as an orally-delivered drug was discontinued due to its narrow therapeutic window related to its short in vivo half-life and systemic side-effects. Our results demonstrate that encapsulating R848 may greatly increase its therapeutic window. Free R848 administered s.c. induced serum TNF-␣ and IL-6 levels that were 50- to 200-fold higher than that observed with SVP-encapsulated R848. The systemic production of TNF-␣, IL-6, and RANTES was suppressed in SVP-R848-injected animals to background levels, while systemic induction of IP-10 and MCP-1 was also greatly attenuated. The reduction in systemic cytokine production is likely due to delivery of nanoparticles to the local draining lymph, direct uptake P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 80000 SVP-PS-CpG (I) PS-CpG, free (I) SVP-PS-CpG (C) PS-CpG, free (C) IFN-γγ (pg/mL) 60000 A 40000 20000 0 0 4 24 48 144 Time after injection (hrs) B 5000 IL-12(p40), pg/ml 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 0 4 24 48 144 Time after injection (hrs) 250 C β, pg/ml IL-1β 200 150 100 50 0 0 4 24 48 144 Time after injection (hrs) Fig. 10. Focused local cytokine induction by SVP-encapsulated, but not free TLR9 agonist CpG. Mice were injected s.c. in a single hind limb with either SVP-PS-CpG 1826 or free PS-CpG 1826. At the times indicated, popliteal LNs from the injection side (ipsilateral, I) and from the opposite side (contralateral, C) were taken and incubated in vitro overnight. Culture supernatants were collected and analyzed for cytokine presence by ELISA. A – IFN-␥, B – IL-12(p40), C – IL-1. Average of two mice per group per time-point is shown. by APCs, and sustained release of R848 over time. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed a strong and sustained local immune activation following subcutaneous administration of SVP-R848, as evidenced by cellular infiltration of the draining LN by APC followed by effector cells, leading to prolonged local production of IFN-␥, IL-12(p40) and IL-1. In contrast, only low levels of LN cellular infiltration and local cytokine production were seen upon administration of free TLR7/8 agonist. Notably, SVP encapsulation of R848 led to a strong induction of cellular immune responses (both local and systemic) even after a single immunization, while free R848 was nearly inactive. 2893 Our results confirm and advance the recent findings of Tacken et al. who reported that nanoparticle encapsulation of TLR3 and 7/8 agonists attenuated the serum cytokine storm and enhanced immunogenicity [71]. In this case, R848 was passively entrapped within the nanoparticle and required antibody-mediated DC targeting for delivery. The reduction in cytokine storm (measured at a single time-point) was not as pronounced as observed in the present study with the SVP-based platform, even though we used 20-fold more R848 [71]. This difference may be due to our use of SVP that contained R848 covalently linked to the PLGA polymer with an acid-labile bond, a design intended to constrain R848 release to the acidic environment within the endosome. SVP encapsulation of a TLR9 agonist, CpG-1826, also provided significant benefit. CpG-1826 belongs to type B CpG, capable of activating B cells and inducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines [14,72,73]. CpG-1826 encapsulation within SVP provided for higher local cytokine production and, when co-delivered with encapsulated antigen, resulted in higher immune responses than antigen admixed with free CpG-1826. Unmodified CpG contains a nuclease-labile phophodiester backbone (PO-CpG) which is known to be rapidly degraded in vivo, thus parenterally administered free CpG must be modified to contain a nuclease resistant phosphorothioate backbone (PS-CpG) to be active in vivo. Importantly, SVP encapsulation enabled utilization of the non-phosphorothioate form of CpG (i.e., PO-CpG) with the same efficiency as PS-CpG. The use of PO-CpG in SVPs may further reduce the potential for systemic immune activation, as any PO-CpG that leaks out of the nanoparticles will be rapidly degraded. Nanoparticle encapsulation of both antigen and adjuvant may have a synergistic benefit by enabling co-delivery of both antigen and adjuvant to APC. The SVP technology allows for either covalent or non-covalent entrapment of a TLR agonist as well as covalent and non-covalent presentation of antigen on the surface or within the nanoparticle. The SVPs are designed to release their payload in the low pH environment of the endolysosomal compartment of APC, which contains TLR7, 8, and 9 as well as MHC class II molecules. The sustained and concomitant release of antigen and adjuvant from SVPs could also contribute to more potent immune responses and better memory cell generation. Our data show that adjuvant and antigen can be delivered in separate nanoparticles. The ability to utilize independently formulated antigen- and TLRagonist-carrying nanoparticles may be advantageous for modular and flexible vaccine design. For example, a two particle approach can provide flexibility in dosing to optimize the ratio of adjuvantto-antigen for a particular application. While vaccines have been an effective and cost-efficient health care intervention for the prophylaxis of many infectious pathogens, new vaccine technology and more potent adjuvants may be required to develop effective therapeutic vaccines for chronic infections, intracellular pathogens, and non-infectious diseases, such as cancer. The immune system is keyed to respond to particulate antigens, such as viruses and bacteria. Synthetic nanoparticles can mimic key elements of viral particles by co-delivering antigen with strong TLR agonists and effectively induce robust cellular and humoral immunity. Finally, one can envision that other immunomodulatory agents could be incorporated into SVPs to further fine-tune the immune response by targeting specific subsets of immune cells, such as CD8 T cells, Th1 cells, Th2 cells, Tfh, Th17 cells, T regulatory cells, B cells, and NK T cells. Collectively, the data reported here suggest an approach to utilize TLR agonists as parenterally administered vaccine adjuvants in a clinical setting while minimizing the risk of systemic adverse reactions. Co-encapsulation of antigen has the added benefit of codelivery of adjuvant and antigen directly to APCs. The SVP approach is currently being evaluated in pre-clinical studies such as cancer and chronic infections, where traditional adjuvants are inadequate, 2894 P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 and in a Phase 1 clinical study for smoking cessation, where high concentrations of antibodies against nicotine are thought to be necessary for therapeutic efficacy. Acknowledgement We thank Aditi Chalishazar, Ingrid Soltero and Alyssa Rague for their expert technical help. Conflict of interest: Petr Ilyinskii, Christopher Roy, Conlin O’Neil, Erica Browning, Lynnelle Pittet, David Altreuter, Lloyd Johnston, and Takashi Kei Kishimoto are employees and shareholders of Selecta Biosciences. Robert Langer, Omid Farokhzad and Ulrich H. von Andrian are founders and shareholders of Selecta Biosciences. Frank Alexis, Elena Tonti, Jinjun Shi, Pamela A. Basto, Aleksandar F. Radovic-Moreno and Matteo Iannacone report no conflict of interest. References [1] Alving CR, Peachman KK, Rao M, Reed SG. Adjuvants for human vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol 2012;24:310–5. [2] Pulendran B, Ahmed R. Immunological mechanisms of vaccination. Nat Immunol 2011;12:509–17. [3] Leroux-Roels G. Unmet needs in modern vaccinology. Adjuvants to improve the immune response. Vaccine 2010;28S:C25–36. [4] Wang W, Singh M. Selection of adjuvants for enhanced vaccine potency. World J Vaccines 2011;1:33–78. [5] Evans TG, McElrath MJ, Matthews T, Montefiori D, Weinhold K, Wolff M, et al. QS-21 promotes an adjuvant effect allowing for reduced antigen dose during HIV-1 envelope subunit immunization in humans. Vaccine 2001;19:2080–91. [6] Buge SL, Ma HL, Amara RR, Wyatt LS, Earl PL, Villinger F, et al. Gp120alum boosting of a Gag-Pol-Env DNA/MVA AIDS vaccine: poorer control of a pathogenic viral challenge. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2003;19:891–900. [7] Patel J, Galey D, Jones J, Ray P, Woodward JG, Nath A, et al. HIV-1 Tat-coated nanoparticles result in enhanced humoral immune responses and neutralizing antibodies compared to alum adjuvant. Vaccine 2006;24:3564–73. [8] Vajdy M, Selby M, Medina-Selby A, Coit D, Hall J, Tandeske L, et al. Hepatitis C virus polyprotein vaccine formulations capable of inducing broad antibody and cellular immune responses. J Gen Virol 2006;87:2253–62. [9] Huleatt JW, Nakaar V, Desai P, Huang Y, Hewitt D, Jacobs A, et al. Potent immunogenicity and efficacy of a universal influenza vaccine candidate comprising a recombinant fusion protein linking influenza M2e to the TLR5 ligand flagellin. Vaccine 2008;26:201–14. [10] Sokolovska A, Hem SL, HogenEsch H. Activation of dendritic cells and induction of CD4(+) T cell differentiation by aluminum-containing adjuvants. Vaccine 2007;25:4575–85. [11] Castilow EM, Olson MR, Varga SM. Understanding respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine-enhanced disease. Immunol Res 2007;39:225–39. [12] Tomai MA, Vasilakos JP. TLR-7 and -8 agonists as vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines 2011;10:405–7. [13] Aguilar JC, Rodríguez EG. Vaccine adjuvants revisited. Vaccine 2007;25:3752–62. [14] Krieg AM, Yi AK, Matson S, Waldschmidt TJ, Bishop GA, Teasdale R, et al. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature 1995;374:546–9. [15] Suzuki K, Mori A, Ishii KJ, Saito J, Singer DS, Klinman DM, et al. Activation of target-tissue immune-recognition molecules by double-stranded polynucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:2285–90. [16] Schenten D, Medzhitov R. The control of adaptive immune responses by the innate immune system. Adv Immunol 2011;109:87–124. [17] Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity 2010;34:637–50. [18] Akira S. Innate immunity and adjuvants. Phil Trans R Soc B 2011;366:2748–55. [19] Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Sanjo H, Hoshino K, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol 2002;3:196–200. [20] Jurk M, Heil F, Vollmer J, Schetter C, Krieg AM, Wagner H, et al. Human TLR7 or TLR8 independently confer responsiveness to the antiviral compound R-848. Nat Immunol 2002;3:499. [21] Edwards AD, Diebold SS, Slack EM, Tomizawa H, Hemmi H, Kaisho T, et al. Toll-like receptor expression in murine DC subsets: lack of TLR7 expression by CD8 alpha+ DC correlates with unresponsiveness to imidazoquinolines. Eur J Immunol 2003;33:827–33. [22] Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science 2004;303:1529–31. [23] Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Kirschning C, Akira S, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via Toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science 2004;303:1526–9. [24] Diebold SS. Recognition of viral single-stranded RNA by Toll-like receptors. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2008;60:813–23. [25] Sato Y, Roman M, Tighe H, Lee D, Corr M, Nguyen MD, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences necessary for effective intradermal gene immunization. Science 1996;273:352–4. [26] Roman M, Martin-Orozco E, Goodman JS, Nguyen MD, Sato Y, Ronaghy A, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences function as T helper-1-promoting adjuvants. Nat Med 1997;3:849–54. [27] Sparwasser T, Miethke T, Lipford G, Borschert K, Häcker H, Heeg K, et al. Bacterial DNA causes septic shock. Nature 1997;386:336–7. [28] Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 2000;408:740–5. [29] Harper DM. Currently approved prophylactic HPV vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2009;8:1663–79. [30] Johnson DA. Synthetic TLR4-active glycolipids as vaccine adjuvants and standalone immunotherapeutics. Curr Top Med Chem 2008;8:64–79. [31] Basith S, Manavalan B, Lee G, Kim SG, Choi S. Toll-like receptor modulators: a patent review (2006–2010). Expert Opin Ther Pat 2011;21:927–44. [32] Wang Y, Abel K, Lantz K, Krieg AM, McChesney MB, Miller CJ. The Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) agonist, imiquimod, and the TLR9 agonist, CpG ODN, induce antiviral cytokines and chemokines but do not prevent vaginal transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus when applied intravaginally to rhesus macaques. J Virol 2005;79:14355–70. [33] Krieg AM. Therapeutic potential of Toll-like receptor 9 activation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006;5:471–84. [34] Wille-Reece U, Flynn BJ, Loré K, Koup RA, Miles AP, Saul A, et al. Toll-like receptor agonists influence the magnitude and quality of memory T cell responses after prime-boost immunization in nonhuman primates. J Exp Med 2006;203:1249–58. [35] Karan D, Krieg AM, Lubaroff DM. Paradoxical enhancement of CD8 T celldependent anti-tumor protection despite reduced CD8 T cell responses with addition of a TLR9 agonist to a tumor vaccine. Int J Cancer 2007;121: 1520–8. [36] Krieg AM. Antiinfective applications of Toll-like receptor 9 agonists. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2007;4:289–94. [37] Vasilakos JP, Smith RMA, Gibson SJ, Lindh JM, Pederson LK, Reiter MJ, et al. Adjuvant activities of immune response modifier R-848: comparison with CpG ODN. Cell Immunol 2000;204:64–74. [38] Doxsee CL, Riter TR, Reiter MJ, Gibson SJ, Vasilakos JP, Kedl RM. The immune response modifier and Toll-like receptor 7 agonist S-27609 selectively induces IL-12 and TNF-alpha production in CD11c+CD11b+CD8− dendritic cells. J Immunol 2003;171:1156–63. [39] Pockros PJ, Guyader D, Patton H, Tong MJ, Wright T, McHutchison JG, et al. Oral resiquimod in chronic HCV infection: safety and efficacy in 2 placebocontrolled, double-blind phase IIa studies. J Hepatol 2007;47:174–82. [40] Malyala P, O’Hagan DT, Singh M. Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of CpG oligonucleotides using biodegradable microparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2009;61:218–25. [41] Bachmann MF, Jennings GT. Vaccine delivery: a matter of size, geometry, kinetics and molecular patterns. Nat Rev Immunol 2010;10:787–96. [42] Kasturi SP, Skountzou I, Albrecht RA, Koutsonanos D, Hua T, Nakaya HI, et al. Programming the magnitude and persistence of antibody responses with innate immunity. Nature 2011;470:543–7. [43] Junt T, Moseman EA, Iannacone M, Massberg S, Lang PA, Boes M, et al. Subcapsular sinus macrophages in lymph nodes clear lymph-borne viruses and present them to antiviral B cells. Nature 2007;450:110–4. [44] Manolova V, Flace A, Bauer M, Schwarz K, Saudan P, Bachmann MF. Nanoparticles target distinct dendritic cell populations according to their size. Eur J Immunol 2008;38:1404–13. [45] Singh M, Kazzaz J, Ugozzoli M, Malyala P, Chesko J, O’Hagan DT. Polylactideco-glycolide microparticles with surface adsorbed antigens as vaccine delivery systems. Curr Drug Deliv 2006;3:115–20. [46] Wagner H. The immunogenicity of CpG-antigen conjugates. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2009;61:243–7. [47] Zambaux MF, Bonneaux F, Gref R, Dellacherie E, Vigneron C. MPEO-PLA nanoparticles: effect of MPEO content on some of their surface properties. J Biomed Mater Res 1999;44:109–15. [48] Dechy-Cabaret O, Martin-Vaca B, Bourissou D. Controlled ring-opening polymerization of lactide and glycolide. Chem Rev 2004;104:6147–76. [49] Astete C, Sabliov C. Synthesis and characterization of PLGA nanoparticles. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2006;17:247–89. [50] Udenfriend SS, Stein S, Böhlen P, Dairman W, Leimgruber W, Weigele M. Fluorescamine: a reagent for assay of amino acids, peptides, proteins, and primary amines in the picomole range. Science 1972;178:871–2. [51] Li C, Goudy K, Hirsch M, Asokan A, Fan Y, Alexander J, et al. Cellular immune response to cryptic epitopes during therapeutic gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:10770–4. [52] Graul A, Castañer J. S-28463. Treatment of hepatitis C interferon inducer. Drugs Future 1999;24:622–7. [53] Carpentier AF, Xie J, Mokhtari K, Delattre JY. Successful treatment of intracranial gliomas in rat by oligodeoxynucleotides containing CpG motifs. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:2469–73. [54] Heckelsmiller K, Rall K, Beck S, Schlamp A, Seiderer J, Jahrsdörfer B, et al. Peritumoral CpG DNA elicits a coordinated response of CD8 T cells and innate effectors to cure established tumors in a murine colon carcinoma model. J Immunol 2002;169:3892–9. P.O. Ilyinskii et al. / Vaccine 32 (2014) 2882–2895 [55] Lonsdorf AS, Kuekrek H, Stern BV, Boehm BO, Lehmann PV, Tary-Lehmann M. Intratumor CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide injection induces protective antitumor T cell immunity. J Immunol 2003;171:3941–6. [56] Sauder DN, Smith MH, Senta-McMillian T, Soria I, Meng TC. Randomized, singleblind, placebo-controlled study of topical application of the immune response modulator resiquimod in healthy adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003;47:3846–52. [57] Carpentier A, Laigle-Donadey F, Zohar S, Capelle L, Behin A, Tibi A, et al. Phase 1 trial of a CpG oligodeoxynucleotide for patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2006;8:60–6. [58] Pashenkov M, Goëss G, Wagner C, Hörmann M, Jandl T, Moser A, et al. Phase II trial of a Toll-like receptor 9-activating oligonucleotide in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5716–24. [59] Mark KE, Corey L, Meng TC, Magaret AS, Huang ML, Selke S, et al. Topical resiquimod 0.01% gel decreases herpes simplex virus type 2 genital shedding: a randomized, controlled trial. J Infect Dis 2007;195:1324–31. [60] Wu CC, Hayashi T, Takabayashi K, Sabet M, Smee DF, Guiney DD, et al. Immunotherapeutic activity of a conjugate of a Toll-like receptor 7 ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:3990–5. [61] Fife KH, Meng TC, Ferris DG, Liu P. Effect of resiquimod 0.01% gel on lesion healing and viral shedding when applied to genital herpes lesions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008;52:477–82. [62] Thomsen LL, Topley P, Daly MG, Brett SJ, Tite JP. Imiquimod and resiquimod in a mouse model: adjuvants for DNA vaccination by immunotherapeutic delivery. Vaccine 2004;22: particle-mediated 1799–809. [63] Chu RS, Targoni OS, Krieg AM, Lehmann PV, Harding CV. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides act as adjuvants that switch on T helper 1 (Th1) immunity. J Exp Med 1997;186:1623–31. 2895 [64] Wille-Reece U, Flynn BJ, Loré K, Koup RA, Kedl RM, Mattapallil JJ, et al. HIV Gag protein conjugated to a Toll-like receptor 7/8 agonist improves the magnitude and quality of Th1 and CD8+ T cell responses in nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:15190–4. [65] Wille-Reece U, Wu CY, Flynn BJ, Kedl RM, Seder RA. Immunization with HIV-1 Gag protein conjugated to a TLR7/8 agonist results in the generation of HIV-1 Gag-specific Th1 and CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol 2005;174:7676–83. [66] Wille-Reece U, Flynn BJ, Loré K, KoupA RA, Miles AP, Saul A, et al. Tolllike receptor agonists influence the magnitude and quality of memory T cell responses after prime-boost immunization in nonhuman primates. J Exp Med 2006;203:1249–58. [67] Klinman DM, Klaschik S, Tomaru K, Shirota H, Tross D, Ikeuchi H. Immunostimulatory CpG oligonucleotides: effect on gene expression and utility as vaccine adjuvants. Vaccine 2010;28:1919–23. [68] Murad YM, Clay TM. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as TLR9 agonists: therapeutic applications in cancer. BioDrugs 2009;23:361–75. [69] O’Hagan DT, De Gregorio E. The path to a successful vaccine adjuvant—‘the long and winding road’. Drug Discov Today 2009;14:541–51. [70] Batista-Duharte A, Lindblad EB, Oviedo-Orta E. Progress in understanding adjuvant immunotoxicity mechanisms. Toxicol Lett 2011;203:97–105. [71] Tacken PJ, Zeelenberg IS, Cruz LJ, van Hout-Kuijer MA, van de Glind G, Fokkink RG, et al. Targeted delivery of TLR ligands to human and mouse dendritic cells strongly enhances adjuvanticity. Blood 2011;118:6836–44. [72] Bauer S, Kirschning CJ, Häcker H, Redecke V, Hausmann S, Akira S, et al. Human TLR9 confers responsiveness to bacterial DNA via species-specific CpG motif recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:9237–42. [73] Verthelyi D, Ishii KJ, Gursel M, Takeshita F, Klinman DM. Human peripheral blood cells differentially recognize and respond to two distinct CPG motifs. J Immunol 2001;166:2372–7.