GUIDANCE ON CONDUCTING DRILLS Advanced Skills in School‐ Based Crisis Preven5on and

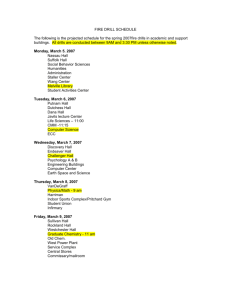

advertisement