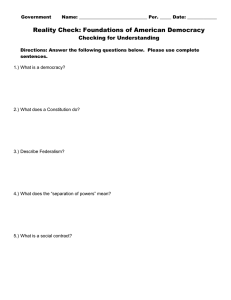

WE THE PEOPLE: THE CONSENT OF THE GOVERNED

advertisement