KADLEC CIRCUIT’S DECISION, HOSPITALS SHOULD ANTICIPATE AN EXPANDED OBLIGATION TO

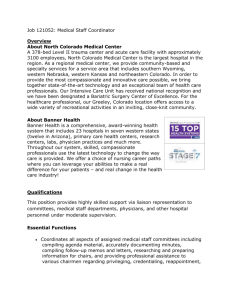

advertisement