I. I

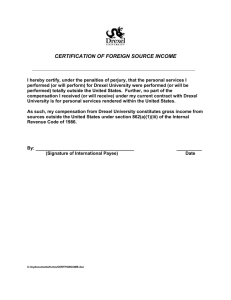

advertisement