Document 11884440

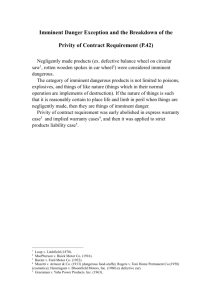

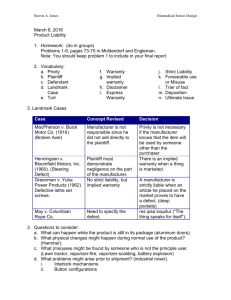

advertisement