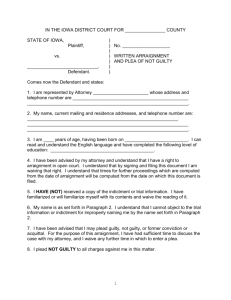

I. S U

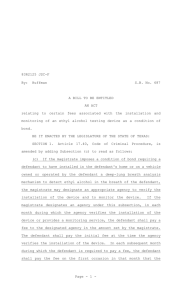

advertisement