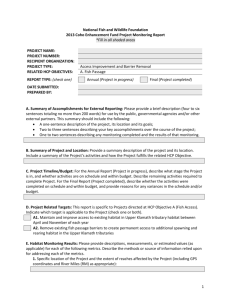

Document 11879371

advertisement