Closure of Trails: A Restoration Strategy or Lack of Management?

advertisement

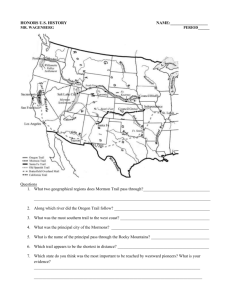

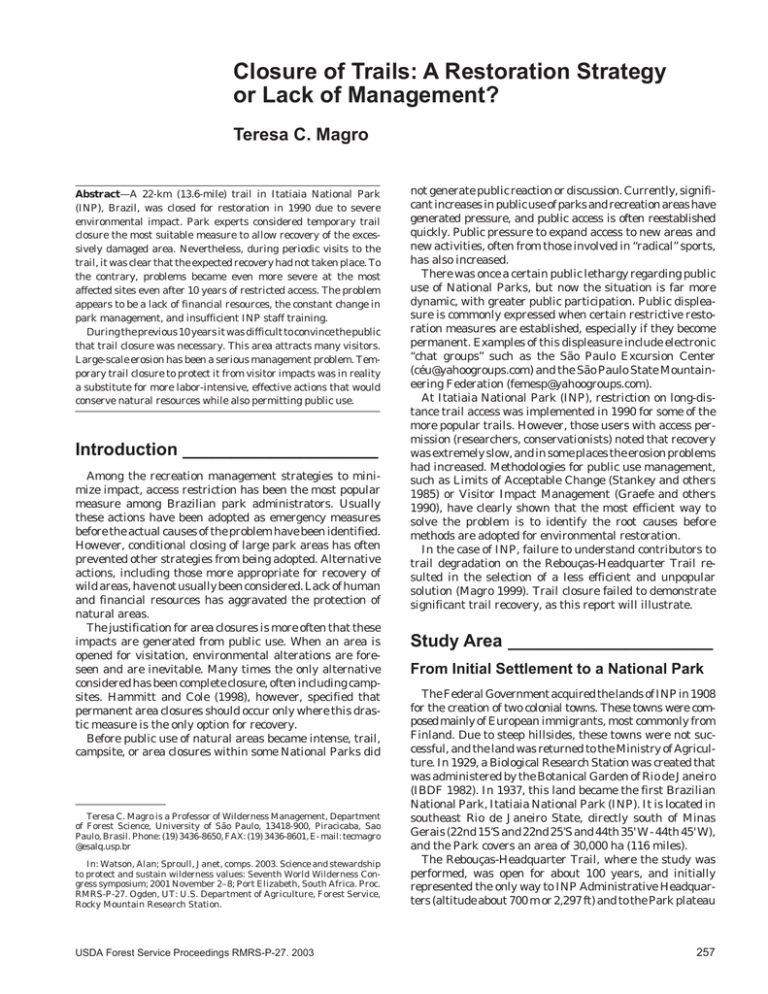

Closure of Trails: A Restoration Strategy or Lack of Management? Teresa C. Magro Abstract—A 22-km (13.6-mile) trail in Itatiaia National Park (INP), Brazil, was closed for restoration in 1990 due to severe environmental impact. Park experts considered temporary trail closure the most suitable measure to allow recovery of the excessively damaged area. Nevertheless, during periodic visits to the trail, it was clear that the expected recovery had not taken place. To the contrary, problems became even more severe at the most affected sites even after 10 years of restricted access. The problem appears to be a lack of financial resources, the constant change in park management, and insufficient INP staff training. During the previous 10 years it was difficult to convince the public that trail closure was necessary. This area attracts many visitors. Large-scale erosion has been a serious management problem. Temporary trail closure to protect it from visitor impacts was in reality a substitute for more labor-intensive, effective actions that would conserve natural resources while also permitting public use. Introduction ____________________ Among the recreation management strategies to minimize impact, access restriction has been the most popular measure among Brazilian park administrators. Usually these actions have been adopted as emergency measures before the actual causes of the problem have been identified. However, conditional closing of large park areas has often prevented other strategies from being adopted. Alternative actions, including those more appropriate for recovery of wild areas, have not usually been considered. Lack of human and financial resources has aggravated the protection of natural areas. The justification for area closures is more often that these impacts are generated from public use. When an area is opened for visitation, environmental alterations are foreseen and are inevitable. Many times the only alternative considered has been complete closure, often including campsites. Hammitt and Cole (1998), however, specified that permanent area closures should occur only where this drastic measure is the only option for recovery. Before public use of natural areas became intense, trail, campsite, or area closures within some National Parks did Teresa C. Magro is a Professor of Wilderness Management, Department of Forest Science, University of São Paulo, 13418-900, Piracicaba, Sao Paulo, Brasil. Phone: (19) 3436-8650, FAX: (19) 3436-8601, E- mail: tecmagro @esalq.usp.br In: Watson, Alan; Sproull, Janet, comps. 2003. Science and stewardship to protect and sustain wilderness values: Seventh World Wilderness Congress symposium; 2001 November 2–8; Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Proc. RMRS-P-27. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-27. 2003 not generate public reaction or discussion. Currently, significant increases in public use of parks and recreation areas have generated pressure, and public access is often reestablished quickly. Public pressure to expand access to new areas and new activities, often from those involved in “radical” sports, has also increased. There was once a certain public lethargy regarding public use of National Parks, but now the situation is far more dynamic, with greater public participation. Public displeasure is commonly expressed when certain restrictive restoration measures are established, especially if they become permanent. Examples of this displeasure include electronic “chat groups” such as the São Paulo Excursion Center (céu@yahoogroups.com) and the São Paulo State Mountaineering Federation (femesp@yahoogroups.com). At Itatiaia National Park (INP), restriction on long-distance trail access was implemented in 1990 for some of the more popular trails. However, those users with access permission (researchers, conservationists) noted that recovery was extremely slow, and in some places the erosion problems had increased. Methodologies for public use management, such as Limits of Acceptable Change (Stankey and others 1985) or Visitor Impact Management (Graefe and others 1990), have clearly shown that the most efficient way to solve the problem is to identify the root causes before methods are adopted for environmental restoration. In the case of INP, failure to understand contributors to trail degradation on the Rebouças-Headquarter Trail resulted in the selection of a less efficient and unpopular solution (Magro 1999). Trail closure failed to demonstrate significant trail recovery, as this report will illustrate. Study Area _____________________ From Initial Settlement to a National Park The Federal Government acquired the lands of INP in 1908 for the creation of two colonial towns. These towns were composed mainly of European immigrants, most commonly from Finland. Due to steep hillsides, these towns were not successful, and the land was returned to the Ministry of Agriculture. In 1929, a Biological Research Station was created that was administered by the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro (IBDF 1982). In 1937, this land became the first Brazilian National Park, Itatiaia National Park (INP). It is located in southeast Rio de Janeiro State, directly south of Minas Gerais (22nd 15’S and 22nd 25’S and 44th 35' W - 44th 45' W), and the Park covers an area of 30,000 ha (116 miles). The Rebouças-Headquarter Trail, where the study was performed, was open for about 100 years, and initially represented the only way to INP Administrative Headquarters (altitude about 700 m or 2,297 ft) and to the Park plateau 257 Magro (maximum altitude of 2,787 m or 9,144 ft). This trail was used initially by those who moved to the town of Mauá, and was used by visitors who hiked or scaled one of the highest peaks in Brazil, Agulhas Negras. Later, cattle that invaded the high altitude pastures and the military that used it for training exercises degraded this trail. Most of the time, INP administrative maintenance practices amounted to weeding and cleaning of trails. Improvements, such as opening and cleaning of drainage channels, were rare events. Such activities, when they occurred, were more frequent before the opening of BR-485, an alternative road that would eventually become the main access to the plateau. The specific objectives of INP, established in the 1982 management plan (IBDF 1982) were: (1) to protect fragments of the Atlantic Rainforest, (2) to provide opportunities for recreation and tourism in a natural way, (3) to protect ecological diversity, (4) to provide opportunities for environmental education, (5) to control erosion and conserve water and air resources, (6) to conserve natural scenic beauties, (7) to provide opportunities for scientific research, (8) to protect animal species in the area, and (9) to make possible public use activities linked directly to area resources, as compatible with other objectives mentioned above. By 1990, the trail had suffered serious erosion problems, with some travel being very risky. The management solution adopted by INP administration was to close the trail to visitor use. Garcia and Pereira’s technical report (1990) was used as justification for this action. These specialists in soils considered the main problem with the Rebouças-Headquarter Trail to be furrow erosion that caused severe gouging. According to these authors, the largest erosion caused along this trail was 7 m (23 ft) in depth and started from a point that was not drained properly. Until 2001, the RebouçasHeadquarter Trail could be used only with special permission from INP. Another backcountry area was temporarily closed to the 2 public in 2001 after a fire consumed about 600 ha (2.3 miles ) of natural vegetation. Again, a technical report on this fire was used as justification for area closure. According to Ribeiro (2001), closing the burnt area to visitation was a crucial measure to guarantee recovery until an action plan was developed. The report recognized that closure had impacts on the local economy, such as with hotels and specialized guides, and suggested that this strategy be used only temporarily. This recent closure, as well as closure of the Rebouças-Headquarter Trail, generated a lot of criticism and protests from excursionists and mountaineers. Methodology ___________________ Institutional Capacity to Administer the Area We considered the administrative or institutional capacities as the ability of INP to successfully solve challenges related to the Park mission. The fundamental maintenance objectives for Brazilian National Parks, according to the National System of Parks and Conservation Units (MMA 2000) are: preserving natural ecosystems of great ecological relevance and scenic beauty, facilitating scientific research, developing educational activities and environmental 258 Closure of Trails: A Restoration Strategy or Lack of management? interpretation, and increasing public contact with nature, which includes ecotourism. Once the INP mission was defined during park creation in 1937, management actions should respect these goals. However, considering the current situation in restricted areas, INP administration has not been successful. We observed that the lack of Park financial resources, constant administrative changes, and insufficient training of Park staff have contributed to this failure. Administrative documents were analyzed to identify Park management activities that could have contributed to attaining their mission. Thirty-four annual reports were consulted, which contained details of management actions executed from 1937 to 1983. In addition to these documents, three former Park Directors were interviewed: Mr. Wanderbilt Duarte de Barros (1940 to 1956), Mr. Pedro Eymard Camelo Melo (1991 to 1995), and Carlos Fernando Pires of Souza (April to September, 1995). Visitor registrations at the “Apple Tree Shelter” were used to estimate trail users from 1928 to 1934, and from 1936 to 1950, and information related to the frequency and form of use of the Rebouças- Headquarter trail was obtained. In these books, INP service and trail maintenance activities were also noted. Results and Discussion __________ Park Maintenance and Administration The first INP administrators presented annual reports to the Forest Service. These documents contain information that shows changes in management and the historical development of public use in this area, including current conditions. These documents establish approximate dates for construction of existing trails, shelter construction, and area maintenance. Using this data, we were able to correlate some problems with the Annual Maintenance Reports (AMRs). Annual Maintenance Reports from 1937 to 1983 were consulted. From 1940 to 1960 there was a certain regularity and uniformity for the presentation of information. Unfortunately, the regular reports stopped in 1970. Documents for 1953, 1961, 1972 to 1978, and 1980 to 1982 were not present in the official files. To obtain complementary information, we consulted other documents, such as requested services, employee problems, or visitor complaints, in addition to spreadsheets with visitor numbers. Less simple than AMR analysis, but indispensable for our conclusions, was information about institutional parameters. In the first years of INP, emphasis was on areas near the administrative building, such as the gardens, surrounding reforestation and general maintenance. This was probably due to two factors: the need for headquarter establishment and the agricultural focus of the previous immigrant colony. Area recovery occupied much time; besides planting arboreal species, the gardens, filled with rosebushes, had to be maintained. Seedlings produced in the Park nursery for restoration and horticulture, including many exotic species, were donated to local institutions and to the Forest Service Administration in Rio de Janeiro. These activities demanded time and consumed many resources. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-27. 2003 Magro Military Training and Cattle There are controversies regarding the effects of military training on current conditions on the Rebouças-Headquarter Trail. The Agulhas Negras Military Academy has been USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-27. 2003 19 19 Year Figure 1—Total visitation in Itatiaia National Park from 1937 to 2000. Registrations corresponding 1951, 1961, 1966, 1971, 1972, and 1976 to 1985 were not found (source: INP Administration). 90,000 80,000 70,000 60,000 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 0 Main Entrance 97 96 19 95 19 94 19 93 19 92 19 19 19 19 91 Plateau 90 Visitors Serrano (1993) found a series of historical documents regarding the first Park users. Using Park registrations, about 2,700 people entered INP from 1925 to 1947. Unfortunately, this number does not accurately represent visitations because many people did not sign the visitor books. In addition, several documents that contained this type of information have been lost. Within Park registrations, origin or nationality was possible to verify, and most visitors at that time were foreigners (70 percent). Between 1937 and 1947, INP AMRs showed an average of 30,049 visitors annually. There were only 4,523 visitors in 1946, but there was a jump of 10,000 visitors in 1947. As observed by Wanderbilt Duarte de Barros, a former INP administrator, soon after the Second World War visitation of INP increased markedly. From registrations and other documents, we estimated visitation from the creation of INP (fig. 1). The data corresponding to 1951, 1961, 1966, 1971, 1972, and from 1976 to 1985, however, were not found in INP files. Visitation values from 1990 to 1997 are more reliable (fig. 2) due to better control at the main Park entrances. However, the values reflect people that paid to enter INP and not the total number of visitors. Those under 10 years old, adults above 70 42 19 47 19 52 19 57 19 62 19 67 19 72 19 77 19 82 19 87 19 92 19 97 20 02 100,000 90,000 80,000 70,000 60,000 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 0 37 Is Visitation in Itatiaia National Park Really a Problem? years, school excursions, researchers, and authorities are exempt from paying the entrance fee. People who hiked the Itatiaia plateau represented about 10 percent of total Park visitors. This is due not only to the attractiveness (waterfalls) of the surroundings of the headquarters, but also the limited infrastructure for receiving visitors and the difficulty of access to the plateau. Access can be better in autumn and winter with the onset of rain. The Itatiaia National Park is strategically located between Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Belo Horizonte, and attracts a larger number of tourists than the Park can handle. But visitation can be considered low when compared with other Brazilian Parks, such as Iguaçu or Tijuca National Parks that receive about a million visitors annually. However, the visitation in Itatiaia is limited to few sites, on weekends, holidays, and school vacations. Part of the low capacity of INP is due to the small staff and limited financial resources. Visitors The need to maintain the administrative headquarters and permanent infrastructure in good condition was also important. The Vargas Presidency (from 1930 to 1945) used the Park as a showplace for diplomats who visited Brazil. When the Federal Capital was in Rio de Janeiro, INP and Serra dos Órgãos National Park represented an excellent view of wild Brazil. Many authorities and diplomats entered the Park while visiting Rio de Janeiro, as verified by reports and the visitor registration books. Other community services were also noted, such as an elementary school, church, electric and phone facility maintenance, internal roads, and access to the city of Itatiaia. Horses and mules were used in Park maintenance and surveillance, and feeding of these animals was often by natural foraging as well as by raising corn. The garden, whose maintenance was time and labor intensive, was reformed in 1943, to simplify and conserve operations. On the other hand, few maintenance activities on the plateau were required, and those that were focused mainly on the studied trail. When this trail was the fastest way to the plateau, it was maintained with certain regularity. However, when the highway was opened with access to the Agulhas Negras, the importance of the trail decreased. Employee records indicated that maintenance of the Rebouças-Headquarter trail was sporadic after BR-485, the new road to the plateau, was opened. Severe erosion, especially the 7-m (23-ft) gully that had motivated trail closing happened by 1979, according to an employee annual report. Beginning in 1971, the AMRs do not mention trail maintenance activities. Employees probably cleared vegetation, mainly in forest areas, but the activity was not constant. Contributing to erosion were fires that hindered vegetation recovery. Closure of Trails: A Restoration Strategy or Lack of management? Year Figure 2—Visitation to Itatiaia National Park from 1990 to 1997. Total number refers to visitors who paid to enter in the park (source: INP Administration). 259 Magro the most frequent trail user since 1956. Park employee depositions have indicated that many impacts were caused by troops, numbering more than 500 men at a time, who used the plateau for military training. A colonel interviewed for this research argued that the training did not happen on trails, but was dispersed and occurred mainly in the Rebouças Shelter. However, we found old artillery pieces, such as rifle cartridges and a cannon reducer, on the trail, indicating that some activity happened on the trail and its environs. Use of heavy boots, bulky equipment, and food by the military during training has aggravated problems here. Certainly the continuous use of the trail contributed to soil compaction and trailbed damage in the most susceptible passages, where it is steep with high soil clay content. The use of the area as a natural cattle pasture and the constant fires that happened during the drought also contributed to the damage in some less resilient sites. In addition, frost also exists here, leaving the vegetation more drought and fire susceptible, and less resistant to trampling by cattle. Dusen (1955) studied the flora of Itatiaia in 1902, and indicated that fire was used as a technique for maintaining cattle pastures. The researcher observed the effect that fires had on vegetation, and he noted that the common frosts usually dried and damaged local flora. Some plants occurred in great abundance in burned areas, while in the areas without burning, there were only two sterile species. Dusen considered that plant development favored the burned areas because the black soil would absorb larger amounts of heat, in comparison with areas that were not burnt. Successive trampling and soil compaction by cattle, along with decreased trail maintenance, were probably responsible for soil structure destruction and increased susceptibility to erosion. Cattle tracks concentrated water toward the main trail, reducing drainage. Another factor linked to trail damage was mule and horse use for transport in the area. Besides the use of horses to carry luggage, construction materials were also transported. According to the 1949 AMR, mules made 1,460 trips to transport the construction material required to build the Massena Shelter, located on the INP plateau. Political Changes and Park Administration Finally, we considered the Park as a whole—its history, use, management, and politics, including political administrative changes during the last decade. The Itatiaia National Park had been endowed with a representative infrastructure, employee houses, well-equipped hiking shelters, a restaurant for the staff, laundry, museum, and a set of roads and trails to permit multiple use. When Rio de Janeiro was the Federal capital, more attention was given to INP, and it was easier to obtain the necessary financial resources. In 1964, the Federal capital was moved to Brasília, and the importance of INP decreased markedly. Once the capital was no longer Rio de Janeiro, the Park stopped attracting national and international attention. Park administration began to receive fewer resources, and had less political weight with politicians in Brasília. According to reports by former employees, the situation in INP worsened during the Military Regime (1964 to 1985) because many bureaucratic positions, such as in the Brazilian Institute of Forest Development (IBDF, now the Brazilian 260 Closure of Trails: A Restoration Strategy or Lack of management? Environment and Renewable Natural Resources Institute, IBAMA), were held by generals or military officers with no training or understanding of the environment. With no sensitivity to conservation of natural resources and without the necessary technical knowledge required to manage a park, problems began to multiply. There was no fuel money for park surveillance vehicles, no new employees were recruited after older employees retired, and there was no money for maintenance. In addition, park vandalism increased due to lack of surveillance and the increase of unemployment. During this period, 12 new National Parks were created, and it was necessary to divide the maintenance resources between the new National Parks and 15 Parks already in existence. Employee recruitment was centralized and only performed in Brasília. This estrangement between Federal bureaucrats and the INP administration (who previously answered only to their superiors in Rio de Janeiro) prevented efficient INP management. Federal Government bureaucratic growth during the Military Regime caused IBDF to become swollen with many employees, complicating simple decisions. This meant that while INP lacked active employees, many supervisors and administrators remained in Brasília or Rio de Janeiro, decreasing park efficiency. Money collected from entrance and parking fees went to Brasília and was effectively lost— few of these fees were returned to INP for improvement and maintenance of existing infrastructure. Budget cuts were more drastic during the New Republic, starting in 1985. Even with the increased concern by the Federal Government for the environment, there were large budget cuts, with “bureaucratic downsizing,” necessitated after the excesses of the Military Regime. Employee numbers were reduced so that today there are only 33 permanent 2 employees to take care of 30,000 ha (116 miles ), and most of these are administrative employees. In addition, there has been very little investment in employee training and ongoing education, which has also harmed the efficiency of area maintenance. Happily, this situation is reversing currently. Conclusions ____________________ There was not a substantial recovery in the RebouçasHeadquarter Trailbed following its closing in 1990, and in some places problems were accentuated. We consider two main reasons for lack of success: (1) no attempts were made to increase vegetation recovery, and (2) the trail was never really closed, remaining open for special groups and military training. Analysis of documents and administrative reports revealed events that allowed continuous trail use and poor decisions made by INP administrators. Besides physical limitations, institutional parameters are necessary for the evaluation of public use impact in natural areas. These factors, planning, and maintenance techniques are essential if correct decisions and appropriate practices are to be established. Acknowledgments ______________ This research was funded by the Boticario Foundation for Protection of Nature (FBPN), the MacArthur Foundation, USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-27. 2003 Magro and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) as part of the Project “Recreational Impact of INP.” We wish to thank several people who helped with the field work: employees of Itatiaia National Park; members of the Agulhas Negras Excursionist Group; Foresters Alexandre Afonso Binelli, Cristina Suarez Copa Velasquez, Flávia Regina Mazziero, and Silvia Yochie Kataoka; and Agronomists Alexandre Mendes Pinho and Fábio Raimo de Oliveira. References _____________________ Dusen, P. K. H. 1955. Contribuições para a flora do Itatiaia. [Contributions of the flora of the Itatiaia.] Rio De Janeiro: Forest Service. 91 p. Garcia, J. M. P.; Pereira, L. E. C. L. 1990. Relatório de visita ao Parque Nacional do Itatiaia—Dezembro/1990. [Visitation Reports of Itatiaia National Park—December/1990.] Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro [Federal University of Rio de Janeiro]. Graefe, A. R.; Kuss, F. R.; Vaske, J. J. 1990. Visitor impact management. The planning framework. Volume 2. Washington, DC: National Parks and Conservation Association. 105 p. Hammitt, W. E.; Cole, D. N. 1998. Wildland recreation. Ecology and management. 2d ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 361 p. Brazilian Institute of Forest Development (IBDF). 1982. Plano de Manejo do Parque Nacional do Itatiaia. M.A.-Instituto Brasileiro USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-27. 2003 Closure of Trails: A Restoration Strategy or Lack of management? de Desenvolvimento Florestal. [Management plan of Itatiaia National Park. Brazilian M.A.- Institute of Forest Development.] Brazilian Institute of Forest Development/Fundação Brasileira para a Conservação da Naturesa [Brazilian Foundation for Nature Conservation]. Brasília. 207 p. Magro, T. C. 1999. Avaliação dos impactos do uso público em uma trilha no planalto do Parque Nacional do Itatiaia. [Evaluation of the impacts of public use on one trail on the plateaus of Itatiaia National Park.] São Paulo: São Carlos Engineering College, São Paulo University. 97 p. Thesis. Ministery of Environment (MMA). 2000. Sistema Nacional de Unidades de Conservação da Natureza. Lei No. 9.985, de 18 de julho de 2000. [National system of units of nature conservation. Law No. 9,985, July 18, 2000.] Brasília: MMA/SBF. 32 p. Ribeiro, K. T. 2001. Incêndio no Planalto do Itatiaia: Parecer técnico sobre o Uso Público do Planalto do Itatiaia imediatamente após o Incêndio. [Fire in the plateaus of the Itatiaia: a technical look at public use of the plateaus of Itatiaia after fire.] Unpublished report on file at: Itatiaia National Park. 11 p. Serrano, C. M. T. 1993. A Invenção do Itatiaia. [The creation of the Itatiaia.] Campinas, Brazil: University of Campinas. 180 p. Thesis. Stankey, G. H.; Cole, D. N.; Lucas, R. C.; Petersen, M. E.; Frissel, S. S. 1985. The Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) system for wilderness planning. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-176. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experimental Station. 37 p. 261