Wilderness Thoughts from the Traditional and Pleasure M. A. S. Rajan

advertisement

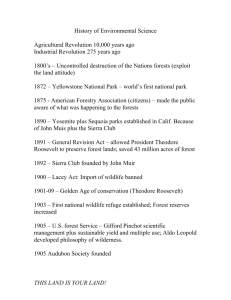

Wilderness Thoughts from the Traditional Lore of India: Of Concern to Peace, Healing, and Pleasure M. A. S. Rajan Abstract—Wilderness can be the origin of human values. Wilderness projects an image. In citing some ideas and excerpts of traditional Indian lore, two very different images are depicted—wild nature as a setting for pleasures of the body, and wilderness as a source of peace and spirituality. What are the benefits that a wilderness area can provide to humankind? Some are indirect benefits, which accrue even while leaving the land absolutely untouched. Others accrue by direct, and let us say benign and limited, utilization of the natural endowments of the land. Among various direct uses is the use of wilderness as an aid for the personal growth of, and therapy and education for, human beings. For the present purpose, we have to take it that the wilderness is already there; whatever may be its origin, good or bad, natural or man-made. As a personal choice without the backing of desk research, I would define wilderness as a given land area that is protected from, or is naturally free from, the depredations of human beings, and supports only that population of life forms, including human beings, which is able to live in self-sufficient synergy and harmony with the land. Clearly there is imperative need to be specific about what it is that we wish to extract from such a wilderness, as a benefit to human beings going there for personal growth or education, before we disturb or destroy this harmony. Omar Khayyam _________________ It is relevant to recite a celebrated Persian poem here. Wilderness occurs in a stanza of the poetic work “Rubaiyat” by Omar Khayyam. It went like this (in the translation by Edward Fitzgerald): Here with a loaf of bread beneath the bough, A flask of wine, a book of verse - and thou Beside me singing in the wilderness And wilderness is paradise enow. Omar Khayyam was a Persian intellectual of the Sufi sect of Islam. He is recognized throughout the East as a mystic. He was not a hedonist, but his mysticism was warmly In: Watson, Alan E.; Aplet, Greg H.; Hendee, John C., comps. 2000. Personal, societal, and ecological values of wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress proceedings on research, management, and allocation, volume II; 1998 October 24–29; Bangalore, India. Proc. RMRS-P-14. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. M.A.S. Rajan is President, Academy of Sanskrit Research (Melkote), freelance writer, retired bureaucrat, 12th Cross Road, Rajamahal Vilas Extension, Bangalore 560080 India, e-mail: masrajan@alumni.ksg.harvard.edu 108 human. To quote a comment of a celebrated Yogic philosopher on the “Rubaiyat” (Yogananda 1996), the poetry of Persia often has two meanings—one inner and one outer. The “Rubaiyat” is, on the face of it, a worldly, even profligate love poem, one written in celebration of earthly pleasures, but in the style of the Sufi mystics, it carries a deep spiritual allegory. The Yogic philosopher has viewed the hidden meaning of the “Rubaiyat” through the prism of Vedanta. According to him, wilderness in this quatrain implies the temporary sense of loss that often precedes true fulfillment. Life then, at first, may seem a “wilderness” devoid of any herbage of hope. With the aid of bread, wine, the leafy shade of tree, book of verse, and the singing of the beloved, the inner void appears clothed with wildflowers of celestial joy. Bread here connotes the life force or energy of the body. Wine is god intoxication, and the bough or tree is the seat of the soul. Book of verse is the inspiration emanating from the heart once it has calmed its restlessness. In Sufi mystical teachings, to depict a soul that is filled with infinite love of God, divinity is given a female form and described as the beloved of the soul. Wilderness for the mystic and for the spiritually inclined is desolation, but a window through which inner happiness can be attained. But the idea that it can be a base or the home for a sensual paradise on earth, a palace for hedonism and the pursuit of physical pleasure would be for them sheer anathema. The dictionary gives to the concept of wilderness a tinge of desolation and distress. When we begin to use a territory that is devoid of habitation and human presence as a substrate for some human benefit, what happens to it? That depends on which one of two readings of Omar Khayyam we choose. One is the wilderness evoked by a literal reading of the “Rubaiyat.” The other is the allegorical view of wilderness seen through the prism of Vedanta. If our choice is the former, the territory will cease to exist as a wilderness. Shuka-Rambha Dialogue _________ An old Sanskrit work comes to mind (Manuscript [n.d.]). This is a poem well known among students and connoisseurs but little known elsewhere. It is skillful poetry, full of prosodic artifice, and interestingly it mentions several forest plants and products. The imagined scene is set in the middle of the forest. Rambha, the temptress from Heaven, and Shuka, the revered sage, are engaged in a duel of words. She has been sent down to earth by the powers in Heaven expressly to subvert the sage’s penance, and she presents her wares by holding forth on the attractions of woman. He USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-14. 2000 counters by extolling the beauty, the power, and the munificence of the Divinity. A feature of the repeating refrain in the poem is that both sage and siren use the identical lament! “Oh, how futile it is for man to come to this forest if….” The temptress describes the sights and sounds of the sylvan surroundings, like the cooing of cuckoos and the fishlike eyes flashing desire through moonlit creepers, as invitations to amorous couplings—PR of the God of Love. The sage describes groups of the devout chanting hymns along the jungle paths, bathing in the holy streams of the surroundings, and holding discourses on the scriptures as the instrumentality to let the love of the Divinity enter one’s heart. (Is one permitted to juxtapose these groups with wilderness trekkers of today?) Rambha then recites stanzas extolling the endowments of a variety of amorous damsels, and, stanza after stanza, Shuka-muni counters with a panegyric on the glories of God. Says Rambha, a damsel in the forest, “…aroused with desire, with a face like the full moon, lips like the bimba fruit, and a delightful voice …sweet of speech, waist adorned with a girdle of golden champak flowers, skilled in the art of love…lovely, kind, with erect breast anointed with sandal, desire-filled eyes…” (and so on in the same vein); who is not “…tightly clasped, closely embraced, shoulder to shoulder…kissed on her pretty belly button…,” (etc.) by the man coming into the forest; such man’s life is verily a waste. Shuka-muni is an enlightened soul who is able to witness the Divinity in anything and everything that he sees. Responding to Rambha stanza for stanza, he says to observe the images, visages, and glories of the Divinity; the man who seeing the forest cannot visualize them and “in his heart grasp his love for the Divinity even for an instant… intensely pray to the Divinity at the moment of enlightenment…cherish the Divinity in his mind when in meditation or penance…,” that man’s life, exhorts the sage, has passed away wastefully. Rambha persists in her line and the dialogue goes on bitterly. How did it end? Legend, rather than the poem, has it that the temptress failed, and the effort to thwart the sage was foiled. In a way, the poem depicts two extremes. The wilderness can be a tantalizing invitation to sensual enjoyment. It can also be the means of sublimating your feelings and moving your thoughts towards the Divinity. It is all in the mind. When we turn to the traditional texts of Sanskrit belonging to the Vedanta tradition, we perceive an approach to wild lands that is not purely homocentric. Deep jungles, high mountains, and the like are typically the spaces in which sages and seers chose to set up their tiny habitations. The sages who desired such spaces were typically savants on a quest for inner peace and greater knowledge of the inner self. There are several passages and texts in old Sanskrit literature that describe the qualities and requirements to be met by these hermitages. The specifications, essentially, were tailored to support and enrich the spiritual effort. For example, places conducive to Dhyana Yoga that is meditation, it is said, should be on plain ground free from stones, sand, and fire, and above all should be pure and sacred, stimulating placidity of the mind without disturbing or agitating it. Natural endowments like rivers, hills and their caves, the seas and their coasts, were taken as visible manifestations USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-14. 2000 of the power that created the Universe and thus were objects to be venerated. They were given the aura of sacredness as places of pilgrimage, and the act of going to them became an important religious practice. The nature of pilgrimage was Prayaschitta, a religious act to atone for sin. A person who goes on pilgrimage with purity of mind, leaving behind his sinful acts and worldly attachments, is relieved of sin, it was said. In some instances the groves were given an extraordinary sacredness. For instance, one legendary forest was worshipped as a Deity itself, as the Creator was believed to have taken abode there. The place was given a name symbolizing the lotus wherefrom the Creator himself arose. Likewise, prominent, uninhabited hills were imbued with personalities and divine powers. Even trees in the forests were similarly bestowed with holiness. There are chapters in the Puranas that say how each particular tree is associated principally with a Deity, and give the legendary basis for that belief. The most prominent of these legends naturally refers to the principal deities in the Pantheon, namely Shiva and Vishnu. The Vata tree is regarded as the symbol of Shiva, and the Asvattha tree that of Vishnu. To this day, sacred rituals echoing the ancient legends are performed around these trees. In the tradition of the Puranas, trees have been imputed with personalities. Trees singly or in a grove in the forest have been said to be able to perform good deeds in support of good people. In one place in the Ramayana, a grove of trees surrounding a hermitage was implored to provide protection and safety to the heroine who had to be left all alone there. In short, forests, mountains, caves, seas, and such are seen as entities with an organic relationship with human beings, typically as objects of reverence and worship, treating them as places that are manifestations of the Creator. Their common base and foundation is the Earth, and the Vedantic tradition was especially reverential toward it. A morning prayer recited on rising from bed says this: O, Mother Earth, adorned by the garb of ocean, with mountains as your breasts, bear with me as I place my feet on you. The injunction in the Upanishads is for Man to regard himself as subservient to the system—not its master. From this was derived the principle of non-accumulation; Man must take from Nature what he needs, not less or more, but shall desist from hoarding to satisfy his greed or gain advantage over Nature. The mental construct about a territory and its endowments is akin to a helper, a protector, and a cleanser of sins. The image is touched with not sadness or desolation, but with spirituality, even if that is at the level of symbol worship. Food for Thought _______________ One can conceive of an array of different Nature-endowed components of wilderness as forming inputs, and many varieties of “benefits” from each such component constitute the possible outputs. We could thus describe an input-output framework with many kinds of inputs and many kinds of desired outputs. A particular set of desired outputs help define wilderness. What is a desired output? We know what it would be if one left it to the temptress or to the sage. A selection has to be 109 made for this modern day and age. Each choice can be linked to an element, or elements, of the wilderness’s natural endowments. Incidentally, what does one do when particular desired outputs fail to mesh with any input from the natural endowments of the given wilderness? It depends on one’s readiness or reluctance to disturb Nature. Typically, available endowments are altered or manipulated to generate the required inputs, or the inputs are brought in from outside. Land use in such cases corrupts wilderness. Finally, what can one make out from this look at one fragment of the traditional lore? Wilderness, or Nature in the wild, needs to be treated as a sentient rather than nonsentient entity, one that is organically related to Man; and is to be taken as helper, a protector, a cleanser of sins. As a manifestation of the Creator in its (nearly) pristine 110 state, an approach marked by respect and restraint would be in order. One has perforce to recognize that the mode of usage of wilderness, concretized as a bundle of desired outputs, should focus on the mind of the user rather than the user’s bodily wants. In this view, it would be appropriate if the modalities of usage are suffused with other-worldliness, and desirable indeed if gross physical land use is altogether avoided. References _____________________ Manuscript (author and date unknown) Rambhashukasamvadah, Mysore: Oriental Research Institute, Mysore. Acc No. 566 Stock No. E 26382. Yogananda, Paramahansa. 1996. The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam explained. New Delhi: UBS Publishers Distributors Ltd. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-14. 2000