International Long-Term Ecological and Monitoring Forest Ecosystem

advertisement

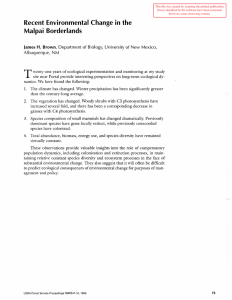

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. International Long-Term Ecological Research: a Role in Research, Inventorying and Monitoring Forest Ecosystem Resources 1 James R. Gosz2 Abstract-Long-term data are crucial to our understanding of environmental change and management. Historically, these studies have been difficult to maintain because ofthe dominance of short term funding programs, a misconception that long-term studies are merely monitoring, and emphasis on short term experimentation or hypothesis testing of specific interactions or processes. The literature also demonstrates a dominance of single, small-scale studies and a focus on a few species. The concept integrates comprehensive understanding of ecosystem processes, model development and the use of regional monitoring and survey data to develop regional understanding of natural resource conditions. The LTER concept is shown as contributing to multiple scale studies and complex assemblages of species. The need for collaborations among the numerous scientists and high-quality programs that are involved in understanding the various areas of our globe is a strong argument for the development of a worldwide network of LTER sites and programs. The main objectives of the ILTER are to: • Promote and enhance understanding of long term ecological phenomena across national and regional boundaries; • Facilitate interaction among participating scientists across sites and disciplines; • Promote comparability of observations and experiments, the integration of research and monitoring, and encourage data exchange; • Enhance training and education; • Contribute to the scientific basis for ecosystem management and improve predictive modeling at larger spatial and temporal scales. LTER sites in the countries of the ILTER Network can provide unparalleled opportunities for cross-site and comparative research efforts on many ofthe world's ecosystems. It is anticipated that each country's program will be part of a global network of scientists and of scientific information that will advance our understanding of not only local and regional, but also global, issues and provide solutions to environmental problems at these scales. These global LTER sites function as "research platforms" that lead to interdisciplinary research, extrapolation to larger areas or regions, provide the scientific basis for management and policy decisions that incorporate social and economic issues. The expected development of a MexicanLTERNetwork will allow the collaboration between Mexico, U.S. and Canada in a North American Regional LTER Network. Ipaper presented at the North American Science Symposium: Toward a Unified Framework for Inventorying and Monitoring Forest Ecosystem Resources, Guadalajara, Mexico, November 1-6,1998. 2 James Gosz is Professor of Biology, Biology Department, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131. 190 A primary role for the ecological sciences is to develop an understanding of the environment that is required for managing our natural resource base in a sustainable manner. Regardless of whether we are testing theory, evaluating new techniques, evaluating management effects, or any of a number of other research endeavors, the ultimate value of such research is to increase our ability to understand the environment. Developing such insights over both time and space scales are important contributions of the many fields of ecology in combination with other disciplines in the biophysical, social and economic sciences. Modern ecological science recognizes that the environment is: • Complex-many interacting factors are involved in ecological processes; • Dynamic-factors vary over time in complex ways; • Spatially variable-heterogeneous and exhibits different patterns at different scales; • Biologically diverse-complex assemblages of thousands of interacting species; • Physical-Chemical-Biological-Social-Economic controlled. Interdisciplinary efforts are needed to understand ecological patterns and processes. This recognition then identifies the serious challenges we have in our research needs. For management of natural resources, the above list indicates that we need to develop our understanding of the environment based on multiple control factors, long term studies, multiple spatial scales, many species interacting in complex ways and interdisciplinary interactions. Since we recognize what is needed to understand the complexity of the environment and manage its natural resources, are we doing it? Are other nations doing it? One way of approaching these questions is to ask why so many countries are now developing Long Term Ecological Research programs and networks. Figure 1 shows the 15 countries that have recognized national programs in Long Term Ecological Research, as well as those near to having such national recognition and those in the initial stages of the process as of October, 1998. This development has occurred in only the last 4 years following an international conference at the end of 1993. The list is dynamic as countries complete the development of their programs and additional countries become interested. Updated versions of the map will be viewable at (http://www.ilternet.edu). Certainly, many or most of these countries have research, inventorying and monitoring programs, so why has there been such interest in the development of an additional research program geared to Long Term Ecological Research? The same question can be asked of the U.S., does our current knowledge base allow the understanding needed to manage our natural resources in a sustainable way. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-12. 1999 Official IL TER Networks • Brazil -Canada ·China - China-Taipei +Colombia -Costa Rica + Czech Republic + Hungary +Israel +Korea +Mongolia +Poland • United Kingdom • United States +Uruguay +Venezuela L TER Networks in development, awaiting formal recognition from their governments Countries expressing interest in developing a network of L TER sites • • • • • • *Bolivia *Chile + Croatia +Oenmark • Ecuador * Finland Argentina Australia Egypt France Ireland Japan • Mexico • Morocco • Paraguay + Portugal • South Africa • Spain * * + + Indonesia Italy Kenya Namibia + Norway • Peru • Slovenia + Sweden .Switzerland • Tanzania + Panama Figure 1 An analysis of the ecological literature in the U.S. provides some idea of how well we are doing in the development of information to meet these needs. Many studies (e.g., chapters and references in Likens 1989) demonstrate that short-term studies can provide misleading results. The environment is very dynamic and varies significantly over time. A study during 1 or 2 years captures only a "snapshot" of the variability and runs the risk of drawing incorrect conclusions about the behavior of ecological systems (Wiens 1997). Although the results of 1-2 years of research may be accurate for that period, extending the interpretation of those results to longer periods is misleading as other periods may have very different results and interpretations. The book by Cody and Smallwood (1996) has many chapters that demonstrate time after time how short-term conclusions may be abridged or overturned by a longer perspective. In spite ofthat knowledge, the literature continues to publish extensively about these snapshots in time. Tilman (1989) analyzed 623 experimental and 180 field studies and reported that over 75% were 1-2 year studies. Analyses of a recent journal of Ecology issue show little change from Tilman's analysis. Of 25 studies in the volume 7 (1998), No.6 issue of Ecology, 84% were based on 1-2 years of data. This indicates that our literature (i.e., knowledge base) is biased toward short-term results and it is difficult to synthesize this knowledge to understand the USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-12. 1999 natural dynamics in the environment. In another analysis of the ecological literature, Weatherhead (1986) found that of 332 plant, invertebrate and vertebrate studies from desert, temperate and tropical habitats, the mean duration was 1-2 years, and further that only about 10% captured "unusual" events such as droughts, wet episodes, insect infestations. We know that these infrequent events are critical in our understanding of forcing functions on the environment and many ecological processes react in a very different way after the "event" than before (Burke, et al. 1991, 1997). Thus, much of our ecological literature fails to document and analyze many of the significant influences on ecological functions. The Volume 7, No. 6 issue of Ecology had no studies that captured an unusual event. Why has there been such emphasis on short-term research in the U.S.? Many reasons, ranging from the pressure on many scientists to publish frequently (using 1-2 years data) to a dominance of short term research awards, pressure to get results fast, and changing issues in funding agencies. Thus, traditional science is biased in certain ways as a result of the systems we have for doing and rewarding science, and as a result, our knowledge base is biased. This seems to be true for many countries suggesting a general human/society influence on the way the environment is studied and research is performed. 191 Analyses of the ecological literature identify other biases relative to the understanding needed for natural resource management. Wiens (unpubl data), Valone and Brown (1996), Kareiva (1994) identify that the spatial scales of study are biased toward single scales that often are done at 1 m 2 • We are aware of the scale dependency of our studies meaning that the scale at which we study the environment "determines" the result that we get. It is similar to studying a process for 1-2 years in that, when we study determines the result just as the scale we use "determines" the result (Levin 1992). The results of the ecological literature in the U.S. are biased to results based on single and small spatial scales! This is especially relevant for landscape management programs that need broad scale and multiple scale analyses. The literature is difficult to use for syntheses of information on how processes vary with scale. The Volume 7, No.6 issue of Ecology showed that all studies but two used a single scale and 50% used the scale of 1 m 2 • Kareiva (1994) and Valone and Brown (1996) also demonstrated that the ecological literature is biased toward studies ofonly 1 or 2 species at a time. Although we know that many thousands of species are involved in ecological processes, it is very difficult to use the current literature to understand how species complexity influences processes important in natural resource management. Finally, the literature is biased toward single discipline results. We have many discipline-specificjournals, disciplinespecific departments in academic institutions, disciplinespecific societies, all of which promote a literature that does not demonstrate the interdisciplinary understanding needed for understanding our environment. Most of our government agencies or ministries have focused missions that further impose a narrow focus. These biases may be the most serious and the most difficult to overcome! While the data from the studies discussed previously are judged by the scientific review process as scientifically valid, they limit the synthesis required to meet the challenge of understanding a complex, dynamic, diverse and heterogeneous environment. We desperately need to develop efforts that can complement the more numerous activities that generate the above biases. Long Term Ecological Research; a Model for Integrated Research Following the International Biological Program (lBP) of the 1970's, the ecological community in the U.S. developed discussions with the National Science Foundation to hold a number ofworkshops on the value oflong term research that could continue the type of science developed during IBP. That resulted in the formation of the Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) program in the U.S. in 1980. The rationale was to develop long term measurements and experiments that would fill what was identified as a deficiency of results at the temporal scales of decades to centuries. From the original designation of6 sites, the program has grown to a network of 21 sites stretching from Alaska to the Antarctic and from habitats as diverse as tropical forests, lakes, deserts, alpine tundra, row agriculture and urban environmentS. Additional sites are expected to be added to the network. That program has demonstrated convincingly of 192 the value oflong-term research, but more importantly, that other types of studies occur that address deficiencies in the research of spatial scales, complex factor control, diverse species assemblages and interdisciplinary interactions. For example, as ecological processes are studied for multiple decades, infrequent events are captured that demonstrate their importance as well as lead natur~lly to questions and the study of the broader scales associated with these infrequent events (e.g., regional drought, Burke et al. 1997). The research at broader scales plus the ability of the comprehensive efforts at long term research sites to utilize multiple platforms from ground-based measurements to satellite imagery allows such cross-scale research. In the U.S. LTER program there has been a natural tendency for multiple scales of research to develop associated with the long-term data sets and studies of many variables. Thus, as a result of performing long term studies that relate to decade temporal scales, the LTER program demonstrates a complementary ability to develop multiple scale studies from local to regional environments. There are other presentations at this conference that will demonstrate the contributions of LTER programs located in forested regions. Here I want to demonstrate the natural progression of scientific questions across spatial scales for a short grass steppe in Colorado. This example demonstrates how the questions evolve following the development of long term data sets and the observations of phenomena that are related to larger spatial scales. The following figures can be viewed at (http:// sgs.cnr.colostate.edulsgshome.htD along with literature for this research site. The Shortgrass Steppe Long Term Ecological Research Project has been conducting regional analysis since 1988. The overall goal in this research has been to understand the current pattern of ecosystem structure and function in the central grasslands of the U.S., and to assess the sensitivity of the region to changes in climate and landuse. The initial analyses, conducted in the late 1980's, focused on the analysis of regional point data, and assessed the relationships between climatic and soil variables and aboveground net primary productivity (Sala et al. 1988) and soil carbon (Burke et al. 1989). Mter analyzing results that included extreme events (e.g., drought) representative of broader scales, the question became ''what area does our site adequately represent?" To what area can we logically extrapolate the results from our site-level investigations (Burke et al. 1990). Using a number of regional databases (Fig. 2), the results suggest that the climate, soils, and landuse of the Shortgrass Steppe LTER site represent approximately 23% of the total shortgrass steppe area. Outside of this region the models that were developed were inaccurate. That led to new efforts to understand why the models were wrong and to reparamaterize the models to work through the central grassland region. More recently, they developed a large spatial database, organized in a geographic information system, of climatic variables (precipitation and temperature), soils data, plant species distributions, and landuse. The three sets of questions for this expanded research program were: 1. What are the regional, spatial controls over plant species distributions, and how will these distributions change under global climate change?; and USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-12. 1999 Figure 2 2. What are the regional, spatial controls over landuse management, how will the"se distributions change under global change, and 3. What are the regional impacts of landuse management on regional climate, and on ecosystem structure and function throughout the region? -~. : Two general techniques were used in this research (Burke et al. 1991). The first was pattern analysis, in which multivariate analysis was conducted on the data to establish important relationships among variables. The second was simulation analysis, in which the spatial database was linked to simulation models to extrapolate across the region and into the future (Coleman et al. 1994). Examples of results from these new studies at the regional scale are the estimate of carbon loss in the region from 1900 to 1995 (fig. 3) and average grain yields (fig. 4) for the region. These results demonstrate another very important aspect of these research-intensive sites. The combination of comprehensive understanding of the ecosystem processes and model development plus regional monitoring and survey information allowed the development of regional simulation models. The research or surveys or monitoring by themselves is insufficient. The combination develops unique capabilities to work at regional scales. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-12. 1999 What is the relationship between long-term research and our understanding of biodiversity or the complex assemblages of species in an environment? Here too, long term studies have been influential. There are two typical results from long-term research sites that show their value. First, because populations of some species vary through time from abundant to many being rare or undetectable a single survey mayor may not record all of the species 'as present. Long-term studies more often detect higher numbers of species by because they see these variations over time. For example, at the Sevilleta LTER site in New Mexico, U.S., (http://sevilleta.unm.edu)vascular plant species richness can vary 3-fold between wet and dry years. For the Northern Temperate Lakes LTER in Wisconsin, U.S., (limnology. wisc.eduf'http://limnosun.limnology. wisc. eduL) zooplankton species richness for a 12-year period was twice the richness for any single year during the period. The second result is based on the value of the long-term research site for research in general. These sites allow a continuity of research efforts because of the protection of the site and generate data of various types that are useful for many studies. This makes the site more and more valuable for other studies and the experience has been that other disciplines are attracted to the site to work on their specific taxonomic groups. This results in a general increase in the 193 Figure 3 species studied on the site and an increase in the identification of species present. Species richness increases directly as a result of research efforts looking for more species! The studies of these species being performed on the same site and over similar periods of time allow increased understanding of how the complexity of species assemblages is related to the functional properties of the ecosystem. The same features that attract many people working on different taxonomic groups also is attractive to people from different disciplines. In addition to the core areas in the U.S. LTER program that require the integration of different disciplines (e.g., population biology, nutrient dynamics, hydrology, climate), the sites become valuable for collaborative studies in areas such as hydrogeology, atmospheric physics/ chemistry, genetics, microbial ecology, systematics, landscape ecology, social/economic sciences as well as development of theory, new techniques and land management approaches. Long term research sites result in intensive studies by many individuals and disciplines working on common areas at similar times that facilitates the integration 194 of information! In addition, the data developed for these studies are managed effectively and archived for the use of other scientists, now and in the future. Data management is an important function in the success of LTER. These sites function like research platforms that concentrate the work of many scientists and disciplines to accomplish studies, integration, and syntheses in ways that are difficult for the more typical research efforts. They complement traditional research in ways that reduce the biases present in the ecological literature. The development ofinterisive and comprehensive research efforts at individual sites provides additional value when cross-site comparisons and experiments are performed. "The power ofthe network approach of the LTER program rests in the ability to compare similar processes (e.g., primary production or decomposition of organic matter) under different ecological conditions. As a result, LTER scientists should be able to understand how fundamental ecological processes operate at different rates and in different ways under different environmental conditions" (Risser et al. 1993). USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-12. 1999 Figure 4 ILTER: Extending the Model Internationally The need for collaborations among the numerous scientists and high-quality programs that are involved in understanding the various areas of our globe is an even stronger argument for the development of a worldwide network of LTER sites and programs. As a result of an international meeting in 1993 to focus exclusively on networking oflongterm ecological research, an International LTER (lLTER) Network was formed with a mission to facilitate international cooperation among scientists engaged in long-term USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-12. 1999 ecological research. Thirty-nine scientists and administrators representing 16 countries participated and developed the initial recommendations for the network. The International LTER needs were identified as: 1. Communication & Information Access for LTER Researchers Worldwide • Determine the general connectivity status ofLTER sites and scientists by country or region • Mter completing a connectivity assessment, organize a clearinghouse system to facilitate technology and skills transfer between sites 195 • Create an information server on the global Internet to provide worldwide access to information and data relevant to international long-term ecological research • Establish an interna~onal LTER (ILTER) server access mechanism (or mechanisms) for researchers in regions presently without access to the international Internet 2. Developing a Global Directory of LTER Research Sites • Develop minimum site capabilities or standards for . inclusion in an ILTER directory • Identify existing and potential LTER sites worldwide • Create both electronic and hard-copy versions of an ILTER directory to be updated regularly • Form a directory working group to help define tasks and secure funding for the creation of an ILTER directory 3. Developing LTER Programs Worldwide • Encourage the pairing of mature and developing sites which share similar ecological settings and encourage cooperation between pairs of established sites within or between countries • Produce an inventory of sources of financial support for ILTER activities and infrastructure at participating sites 4. Scaling, Sampling and Standardization: Some Design Issues. The following questions should be addressed by LTER sites: • Will phenomena, which occur over long time scales, be adequately sampled over appropriate spatial scales? • What is the spatial and temporal range over which site data can be legitimately extrapolated, and what method(s) will be used? • How much effort will be required for synthesis and intersite comparison, and has flexibility for subsequent adjustment of observations been incorporated into the design? • Have the selected measurements been adequately tested, and have the required precision and frequency of observations been specified? • Does the range of variables selected adequately reflect the full range of driving, state and response variables for the system under investigation? 5. Education, Public Relations and Relationships with Decisionmakers • ILTER sites should be used as sources of information for formal higher education and interdisciplinary curricula development • ILTERsites should be used as sources of information for elementary and secondary school curricula development • ILTER sites and networks should provide clear and accurate information on LTER research to the general public and decisionmakers The ILTER Network Committee has continued and broadened its activities through annual meetings. Following the initial conference in the United States in 1993, meetings have been held in the U.K. (1994), Hungary (1995), Panama! Costa Rica (1996), Taiwan (1997) and Italy (1998). The committee has established the following mission statements, based primarily on the 1993 conference: 1. Promote and enhance the understanding of long-term ecological phenomena across national and regional boundaries; 196 2. Promote comparative analysis and synthesis across sites; 3. Facilitate interaction among participating scientists across disciplines and sites; 4. Promote comparability of observations and experiments, integration of research and monitoring, and encourage data exchange; 5. Enhance training and education in comparative longterm ecological research and its relevant technologies; 6. Contribute to the scientific basis for ecosystem management; 7. Facilitate international collaboration among comprehensive, site-based, long-term, ecological research programs; and 8. Facilitate development of such programs in regions where they currently do not exist. Each country must assess its own needs and resources if it wishes to involve itself in an ILTER program. Each will have a unique set of opportunities and limitations that are best evaluated by the scientists and policy makers of that country. The typical procedure for a country is for the scientists of that country, along with the funding agencies, to decide whether to endorse the premise that ecology and environmental management are significantly benefited by studies in long-term and broad spatial scales. A plan is then developed that establishes the context and mission for such studies, sites and programs identified that will contribute to this mission, and support is obtained from within that country or international organizations for implementation and continued maintenance. It is anticipated that each country's program will be part of a global network of scientists and of scientific information that will advance our understanding of not only local and regional, but also global issues and provide solutions to environmental problems at these scales (Gosz 1996). A more recent development among a number of countries is the formation of Regional LTER Networks. Neighboring countries often have similar issues and have demonstrated increased opportunities for collaboration and increased support to other countries in the region that are attempting to develop their own LTER Network. The East Asian-Pacific Regional LTER Network and the Latin American Regional LTER Network have been formed and are holding their own annual meetings in addition to the ILTER annual meetings. A Central Europe Regional LTER Network is being planned at this time and this conference will play an important role in the development of a North American Regional LTER Network. Development of a North American Regional LTER Network _ _ __ Collaboration among Canada's Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Network (EMAN, http://www.cciw.ca! emanl), the U.S. LTER Network (http://www.lternet.edu), and a planned Mexican LTER Network (MEXLTER, http:// www.ilternet.edulsitesimexico/) offers excellent possibilities for integrating the LTER research model for North America. The following description of the Mexican LTER Network is a statement found at their web site listed above. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-12. 1999 Mexico's participation in the International Long Term Ecological Research Network is important for several reasons. As a result of Mexico's geographic situation and topographic complexity, it supports high levels of species and ecosystem diversity, representing a major fraction of the earth's biota. It is imperative that the country understands and protects this heritage because the combination of extensive rural poverty, low technical support and high population growth has led to a rapid land-use transformation in the country. Scientific understanding of the effects of landuse changes on natural ecosystems is necessary for developing practices toward sustainable management and conserva tion. Addi tionally, Mexico is affected by ecological processes that operate at continental scales, such as the EI NinoSouthern Oscillation, which occur infrequently and can only be understood through collaborative long-term and largescale efforts. Finally, the proximity of Mexico to a wellestablished network of long-term studies creates the opportunity for scientific cooperation and development of human resources. The fundamental philosophy of the MEXLTER will be to address ecological research at large temporal and spatial scales in a fashion that has not been generally practiced in Mexico. Through the network structure, sites will have similar projects and share standardized data. The MEXLTER program is designed to encompass terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, including managed ones. National-level studies should allow comparisons within and across biomes. At an international level, it should facilitate comparisons within and across biomes in different geographical areas. Therefore, the network should have representation of the major biomes within the country, making it desirable to procure replicated sites within biomes. The objectives of the MEXLTER are as follows: 1. Establishing a network of sites to allow Mexican scientists to address ecological issues in an interdisciplinary way on broad spatial and temporal scales. A corollary is to understand the role of biological diversity in ecosystem processes and in the provision of services to the biosphere, including humans. 2. Creating a legacy of well-designed and documented experiments and observations for future generations. At present the scientific community in Mexico is in the process of formally establishing the MEXLTER, working on an agreement with the National Council of Science and Technology to obtain funding for beginning the Network Office and the initial network of sites. Seven core subjects will define the basic theoretical framework for the research conducted at the LTER sites. These subject areas address the most relevant functional and structural features of ecosystems, and the most pressing environmental issues for human welfare. Within each topic area, there will be a background and a hierarchy of three levels of detail, which will set the priorities for data acquisition. The core areas are: • Patterns and control of ecosystem primary productivity • Patterns and control of water, carbon and nutrient dynamics in ecosystems • The role of biodiversity in the structure and functioning of the ecosystem • Patterns and frequency of ecosystem disturbance USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-12. 1999 • Effect of climate change on the structure and functioning of ecosystems • Interactions at the interface level between managed and natural ecosystems • Defining criteria for ecosystem management and conservation One of the reasons for establishing a network of research sites is to encourage the development of large-scale and comparative studies. The establishment of such studies will require frequent communication among potential collaborators in order to define possible joint studies. In order to facilitate such communication, the network will organize meetings of all the scientists involved in the long-term research at the participating sites. Meetings will be held every other year during the development of the project and will be designed to maximize interchange of ideas during the formative phase of each research project. Additional goals of the meetings will include the introduction of par ticipating scientists to the concepts of long-term research networks and the importance of key aspects such as data management and the use of remotely sensed data. Collaboration of the MEXLTER with regional networks will be made through regular regional conferences. Presently, the MEXLTER is actively involved with both the North American and Latin American regional networks. Collaboration with the global network will be made via the Internet and specific meetings. Interactions with GTOS ----------------LTER sites in the countries of the ILTER Network now can provide unparalleled opportunities for cross-site and comparative research efforts on many of the world's ecosystems at levels from genes to landscapes. These global LTER sites function as "research platforms" that lead to interdisciplinary research, extrapolation to larger areas or regions, provide the scientific basis for management and policy decisions that incorporate social and economic issues, and attract scientists from other sites and networks, expanding the effective "network" of sites. The ILTER Network is now well positioned to interact with other international activities such as the International Geosphere Biosphere Program (IGBP) and the Global Terrestrial Observing System (GTOS). Other international networks are being developed and many have complementary obj ectives. It will be important to develop collaboration with these networks to maximize the value and efficiency of international research efforts. The Global Terrestrial Observing System (GTOS) was created to provide policy makers, resource managers and researchers with access to the data needed to detect, quantify, locate, understand and warn of changes (especially reduction) in the capacity ofterrestrial ecosystems to support sustainable development. The GTOS focus is on five key development issues of global or regional concern; • • • • • changes in land quality availability of freshwater resources loss of biodiversity pollution and toxicity climate change 197 ILTER and GTOS have an ongoing collaboration and ILTER sites will be used in various GTOS demonstration projects and supply data sets for international use. ILTER/GTOS Benefits We anticipate that international collaboration of programs like GTOS and ILTER will have a number of benefits: 1. Designation as a 'participating network'. In many cases, this will strengthen the justification for continuing measurements at the site(s). It will also provide a natural focus for coordinated, multidisciplinary measu,rements and programs. 2. Enhanced collaboration. By being included in a global network the opportunities for coordinated observations and scientific collaboration will be much improved. Individual networks will learn from the experiences of other networks for science, operation and data management. 3. Contribution to global environmental conventions: climate, biodiversity, desertification, and endangered species among others. The participating networks will make an important contribution to meeting the political and scientific objectives of these conventions and the responsibility taken on by their respective countries. 4. Enhancement of the network's impact. In most cases, the effectiveness of a network's operation will be enhanced if the collected data are used by others. Also, a network's program will benefit by having a structured access to data from other similar networks. 5. Facilitating access to comparative data from a wider range of sties to improve the interpretation of a particular site's data. 6. Visibility, both nationally and internationally, through participating in the networks and in various initiatives. 7. Opportunities for additional funding and benefits. Although the networks will be largely self-financed, it is expected that supplemental funding will be sought for special initiatives, for pilot projects, to fill gaps in observations, and for other reasons. The leverage provided by GTOS and ILTER will be very helpful in making the case for new funds. 198 literature Cited Burke, I.C., C. Yonkers, W.J. Parton, C.V. Cole, K. Flach, and D.S. Scbimel. 1989. Texture, climate, and cultivation effects on organic matter in Grassland Soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 53(3): 800-805. Burke,I.C.,D.S. Scbimel,W.J. Parton, C.M. Yonker, L.A.Joyce, and W.K. Lauenroth. 1990. Regional modeling of grassland biogeochemistry using GIS. Landscape Ecology: 45-54. Burke, I.C., T.G.F. Kittel, W.K. Lauenroth, P. Snook, C.M. Yonker and W.J. Parton. 1991. Regional analysis of the central Great Plains, sensitivity to climate variability. BioScience 41: 685-692. Burke, I.C., W.K. Lauenroth, and W.J. Parton. 1997. Regional and temporal variation in net primary production and nitrogen mineralization in grasslands. Ecology 78: 1330-1340. Coleman, M.B., T.L. Bearly, I.C. Burke,and W.K. Lauenroth 1994. Linking ecological simulation models to geographic information systems: anautomatedsolutionpp. 397-412. In Michener, W. and J. Brunt (eds). Environmental Information Management and Analysis: Ecosystem to Global Scales. Taylor and Francis, London. Cody, M.L. and J.A. Smallwood. (eds.). 1967. Long-term Studies of Vertebrate Communities. Academic Press. Gosz, J.R. 1996. International long-term ecological research: priorities and opportunities. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 11: 444. Kareiva, P. 1994. Higher order interactions as a foil to reductionist ecology. Ecology. 75: 1527-1528. Levin, S. A. (1992). The problem of pattern and scale in ecology. Ecology. 73: 1943-1967. Likens, G.E. (ed.). 1989. Long-term Studies in Ecology. SpringerVerlag, New York. Risser P.G., J. Lubchenco, N.L. Christensen, P.J. Dillon, L.n. Gomez, D.J. Jacob, P.L. Johnson, P. Matson, N.A. Moran, and T. Rosswall. 1993. Ten-Year Review ofthe National Science Foundation Long-Term Ecological Researth (LTER) Program. Sala, O.E., W.J. Parton, L.A. Joyce, and W.K. Lauenroth. 1988. Primary production ofthe central grassland region of the United States: Spatial pattern and major controls. Ecology. 69: 40-45. Tilman, D. 1989. Ecological experimentation: strengths and conceptual problems. pp. 136-157. In. Likens, G.E. (ed). Long-Term Studies in Ecology. Springer-Verlag, New York. Valone, T.J. and J.H. Brown. 1996. Desert rodents; Long-term responses to natural changes and experimental manipulations. pp. 555-583. In: Cody, M.L. and J.A. Smallwood (eds). Long-Term Studies of Vertebrate Communities. Academic Press. Weatherhead, P.J. 1986. How unusual are unusual events? American Naturalist. 128: 150-154. Wiens, J. 1997. Lengthy ecological studies. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 12: 499. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-12. 1999